One side sought to prove that Arizona’s former attorney general and schools chief had racist motives against Mexican-Americans in crafting and enforcing a state law banning ethnic studies programs, while the other side painted him as a crusader against racism.

In the second week of bench trial to determine whether state officials had discriminatory intent in enacting and enforcing the 2010 law, Tom Horne took the witness stand Tuesday. The trial is overseen by U.S Circuit Judge A. Wallace Tashima in Tucson in the U.S. District Court in Arizona.

The case was brought forward by former teachers and students of Tucson Unified School District’s Mexican American Studies program, saying the law violated their constitutional rights. Tashima dismissed their claim in 2013, but the case was remanded by a federal appeals court two years after that.

The chain of events that led to the program’s eventual demise in 2011 began with a speech in 2006 at Tucson High Magnet School by Dolores Huerta, a civil-rights activist and co-founder of a farmworkers union. During the speech, she reportedly said Republicans hate Latinos.

In response, Horne, a Republican, sent his deputy, Margaret Garcia Dugan, to speak at the school to present “the other side.” When she spoke, several students, some of whom were Mexican American Studies students, staged a silent protest, which Horne characterized as “rude” and “educationally disruptive.”

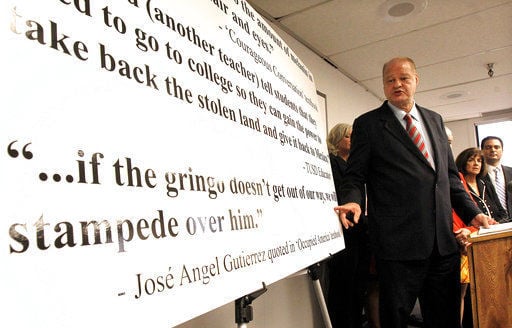

Horne said he concluded that Mexican American Studies teachers, who he said were ideological and radical, were responsible for mobilizing the students after talking with other former teachers and sought to eliminate the program.

Attorney Jim Quinn, who represents the plaintiffs, pointed out through his questioning that Horne used selective sources and outdated information to issue findings that MAS has violated the ethnic studies law.

The attorney also alleged that Horne did not investigate other ethnic studies programs or a Tucson charter school named after Paulo Freire, a Brazilian philosopher, whom both he and Huppenthal took issue with. Horne said repeatedly during the trial that he was opposed to any educational program that divides students based on race, which he said was racist.

Quinn also exhibited material and video clips from when Horne was campaigning for the state attorney general’s seat that showed him boasting about having fought to end MAS and the state’s bilingual education program, and supporting other policies or actions that many Latino Americans opposed, including suing Maricopa Community College to end in-state tuition for undocumented students who were granted protection against immediate deportation.

Horne said his support for “anti-illegal immigration” is conflated with “anti-Mexican” or “anti-immigration.”

“I’m an immigrant myself,” he said. Horne is from Montreal but has lived in Arizona since the 1970s.

The former attorney general repeatedly said he wanted to eliminate Mexican American Studies because of the number of complaints he had received and because he found evidence of violations. In his findings, Horne cited interviews with teachers and quotes from classroom material.

Robert Ellman, an attorney working with the state, asked Horne about his role in starting an anti-racism program in the Paradise Valley Unified School District, where he was formerly a board member, and his work with officials in Mexico.

Horne testified that he had good relations with the education department in Sonora, Mexico, and that as attorney general, he helped train Mexican attorneys in oral trial.

“My whole life has been a crusade against racism,” Horne said.