Several million dollars worth of new flood infrastructure could soon be put to the test on Tucson’s northwest side, as monsoon season officially gets underway.

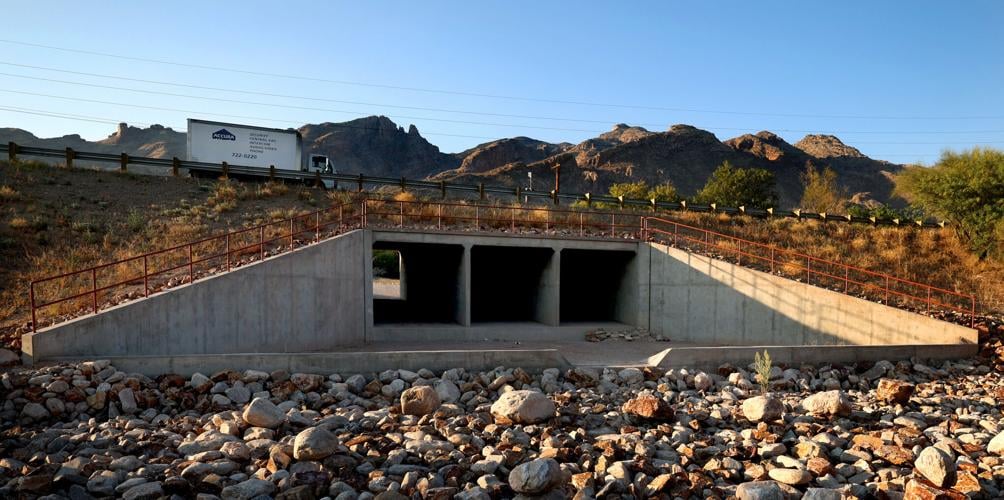

This will be the first full summer of action for an almost $2.4 million culvert project in the Catalina Foothills that is designed to safely carry Finger Rock Wash water under Skyline Drive near Columbus Boulevard.

That work was initiated in 2020, after the Bighorn Fire burned almost 120,000 acres in the Santa Catalina Mountains and increased the risk of flooding in the Coronado Foothills Estates subdivision.

Since then, two major flash floods have damaged homes along Finger Rock Wash and threatened the stability of the earthen berm that holds up Skyline, a potential hazard officials compared to a dam failure.

People are also reading…

A street sign lies on the side of the road at the corner of Havasu Road and Columbus Boulevard after a flash flood swept down Finger Rock Wash on July 31, 2022, damaging a number of homes in Tucson’s Coronado Foothills Estates subdivision.

The berm and the road on top of it are now fortified with three 12-foot-by-10-foot concrete box culverts built to replace a single, 2-foot pipe that previously provided the only outlet for the wash.

The project was overseen by the Pima County Department of Transportation and paid for with state wildfire mitigation funding secured by the Pima County Regional Flood Control District.

Meanwhile, federal grant money is being used to launch work this week on $4.3 million worth of levee improvements along more than 4 miles of the Cañada Del Oro wash.

Flood district deputy director Brian Jones said the project area stretches from just east of Oracle Road to just west of La Cañada Drive, where enough sediment has collected in the wash channel to require the levee walls to be raised on both sides.

The channel still has enough capacity to handle a major torrent, he said, but the sediment build-up has cut into what flood officials call the levee’s “freeboard,” in this case a 3-foot safety cushion above the level of a 100-year flood.

Most of the levee walls lining the Cañada Del Oro were built in 1987.

A cyclist rides along the flooded Loop bike trail along the Cañada del Oro Wash as it flows with the runoff from several monsoon storms on July 14, 2021.

In some places, the freeboard can be restored by removing some sediment from the channel or raising the levee a few inches by simply adding a new layer of pavement to the Loop, the county’s walking and biking path along the wash. Elsewhere, though, the levee wall needs to be raised by as much as 3 feet, said Jones, who also serves as floodplain administrator for the district.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency is providing $2.5 million for the project through its Hazard Mitigation Grant Program, leaving the district to cover the remaining $1.8 million.

According to FEMA, a hydrologic study conducted after the Bighorn Fire found significant changes to the Cañada Del Oro, with “increased risk of flooding and debris flow in areas that were previously low risk.”

Managing sediment in the county’s mostly dry rivers and washes is a big part of what the district does.

Every three to five years, surveyors will fly over the county’s major watercourses and use lasers to collect precise elevation data. That state-of-the-art topographic mapping helps the district decide which channels are most in need of clearing.

Almost half a million cubic yards of sediment have been removed from local washes and rivers over the past five years alone.

“We feel like we’re in good shape,” Jones said. “We feel like we’re on top of all our maintenance heading into the upcoming monsoon.”

House hunters

In addition to the FEMA funding for the levee project, the district is seeking about $1.2 million in federal grant money to buy and tear down at least two more houses along the Finger Rock Wash in Coronado Foothills Estates.

In the event of a 100-year flood, Jones said, “we predict these homes will be in upwards of two feet of water.”

A 100-year flood is a term hydrologists use for a flow event with a one-in-100 chance of happening in any given year.

Six homes in the subdivision have already been acquired — at a cost of about $4.3 million — through the county’s Flood-prone Land Acquisition Program, which was created after the devastating floods of 1983 to proactively keep homes and businesses out of at-risk areas.

What will this year's monsoon season look like in Southern Arizona? Here's a preview from the National Weather Service's Tucson Forecast Office.

The district spent another $507,000 to demolish the six houses, including one that operated as an assisted living facility until July 31, 2022, when 10 residents had to be evacuated by firefighters during a flood that filled the structure with several feet of water.

Clearing the properties meant tearing out a couple of swimming pools and carefully disposing of asbestos from structures built at least 50 years ago, Jones said.

Just one occupied house now stands along a quarter-mile stretch of Havasu Road that was mapped out in the early 1960s, prior to the creation of the flood district or the adoption of county regulations against building in flood zones.

Jones said FLAP only buys from willing sellers and only receives about $1 million a year to purchase property at appraised value. That’s why the district applied for FEMA funding for its next two acquisitions in Coronado Foothills Estates: to keep from spending all of its FLAP money for the entire county in a single Foothills neighborhood, he said.

Going with flow

Before the six homes were demolished early this year, about 40 volunteers from the Tucson Cactus and Succulent Society spent several days rescuing almost 300 cactuses from the properties.

Julie Shulick, urban rescue coordinator for the nonprofit society, said most of the plants collected in December and January were nonnative cactuses such as golden barrels, Mexican fence posts and Peruvian apples.

They were either sold to support the society’s work or planted at Pima Prickly Park, a 9-acre cactus garden maintained by the county and the society near the west end of River Road.

Shulick said the only native plants rescued — mostly saguaros and native barrel cactuses — were the ones directly in the way of the demolition crews. The rest were left in place as part of the county’s plan to restore the now-vacant land as a natural, desert riparian area.

An empty lot, except for a few palm trees and brick wall, are all that’s left of a home in the 4200 block of East Havasu Road, just east of Columbus Boulevard. The home was one in a flood zone the county bought and leveled.

Jones said a few brick retaining walls were left in place, and some earthwork was done here and there to try to preserve the overall grade of the properties. Workers also laid down a layer of native seeds in hopes of getting some plants to grow where the homes once stood.

Ultimately, officials want to make sure that removing the houses didn’t make the flood situation any worse for the neighboring properties.

“We’ll see what happens. We’ll see if they get some flows this year,” he said.

June 15 marks the official start to the monsoon season, which lasts until the end of September. Forecasters from the National Weather Service and elsewhere are predicting hotter and drier conditions than normal across much of Arizona this summer.

Of course, all it takes is a few downpours in the wrong spots to create problems. As Jones pointed out, 2020 was the second driest monsoon season on record in Tucson, but “we still had flooded houses.”

“A prediction of a dry monsoon doesn’t let us off the hook,” he said. “Even in dry monsoons, there are still significant storms, and those storms cause flooding.”

Several million dollars worth of new flood infrastructure could soon be put to the test on Tucson’s northwest side, as monsoon season officially gets underway.

This will be the first full summer of action for an almost $2.4 million culvert project in the Catalina Foothills that is designed to safely carry Finger Rock Wash water under Skyline Drive near Columbus Boulevard.

That work was initiated in 2020, after the Bighorn Fire burned almost 120,000 acres in the Santa Catalina Mountains and increased the risk of flooding in the Coronado Foothills Estates subdivision.

Since then, two major flash floods have damaged homes along Finger Rock Wash and threatened the stability of the earthen berm that holds up Skyline, a potential hazard officials compared to a dam failure.

A street sign lies on the side of the road at the corner of Havasu Road and Columbus Boulevard after a flash flood swept down Finger Rock Wash on July 31, 2022, damaging a number of homes in Tucson’s Coronado Foothills Estates subdivision.

The berm and the road on top of it are now fortified with three 12-foot-by-10-foot concrete box culverts built to replace a single, 2-foot pipe that previously provided the only outlet for the wash.

The project was overseen by the Pima County Department of Transportation and paid for with state wildfire mitigation funding secured by the Pima County Regional Flood Control District.

Meanwhile, federal grant money is being used to launch work this week on $4.3 million worth of levee improvements along more than 4 miles of the Cañada Del Oro wash.

Flood district deputy director Brian Jones said the project area stretches from just east of Oracle Road to just west of La Cañada Drive, where enough sediment has collected in the wash channel to require the levee walls to be raised on both sides.

The channel still has enough capacity to handle a major torrent, he said, but the sediment build-up has cut into what flood officials call the levee’s “freeboard,” in this case a 3-foot safety cushion above the level of a 100-year flood.

Most of the levee walls lining the Cañada Del Oro were built in 1987.

A cyclist rides along the flooded Loop bike trail along the Cañada del Oro Wash as it flows with the runoff from several monsoon storms on July 14, 2021.

In some places, the freeboard can be restored by removing some sediment from the channel or raising the levee a few inches by simply adding a new layer of pavement to the Loop, the county’s walking and biking path along the wash. Elsewhere, though, the levee wall needs to be raised by as much as 3 feet, said Jones, who also serves as floodplain administrator for the district.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency is providing $2.5 million for the project through its Hazard Mitigation Grant Program, leaving the district to cover the remaining $1.8 million.

According to FEMA, a hydrologic study conducted after the Bighorn Fire found significant changes to the Cañada Del Oro, with “increased risk of flooding and debris flow in areas that were previously low risk.”

Managing sediment in the county’s mostly dry rivers and washes is a big part of what the district does.

Every three to five years, surveyors will fly over the county’s major watercourses and use lasers to collect precise elevation data. That state-of-the-art topographic mapping helps the district decide which channels are most in need of clearing.

Almost half a million cubic yards of sediment have been removed from local washes and rivers over the past five years alone.

“We feel like we’re in good shape,” Jones said. “We feel like we’re on top of all our maintenance heading into the upcoming monsoon.”

House hunters

In addition to the FEMA funding for the levee project, the district is seeking about $1.2 million in federal grant money to buy and tear down at least two more houses along the Finger Rock Wash in Coronado Foothills Estates.

In the event of a 100-year flood, Jones said, “we predict these homes will be in upwards of two feet of water.”

A 100-year flood is a term hydrologists use for a flow event with a one-in-100 chance of happening in any given year.

Six homes in the subdivision have already been acquired — at a cost of about $4.3 million — through the county’s Flood-prone Land Acquisition Program, which was created after the devastating floods of 1983 to proactively keep homes and businesses out of at-risk areas.

What will this year's monsoon season look like in Southern Arizona? Here's a preview from the National Weather Service's Tucson Forecast Office.

The district spent another $507,000 to demolish the six houses, including one that operated as an assisted living facility until July 31, 2022, when 10 residents had to be evacuated by firefighters during a flood that filled the structure with several feet of water.

Clearing the properties meant tearing out a couple of swimming pools and carefully disposing of asbestos from structures built at least 50 years ago, Jones said.

Just one occupied house now stands along a quarter-mile stretch of Havasu Road that was mapped out in the early 1960s, prior to the creation of the flood district or the adoption of county regulations against building in flood zones.

Jones said FLAP only buys from willing sellers and only receives about $1 million a year to purchase property at appraised value. That’s why the district applied for FEMA funding for its next two acquisitions in Coronado Foothills Estates: to keep from spending all of its FLAP money for the entire county in a single Foothills neighborhood, he said.

Going with flow

Before the six homes were demolished early this year, about 40 volunteers from the Tucson Cactus and Succulent Society spent several days rescuing almost 300 cactuses from the properties.

Julie Shulick, urban rescue coordinator for the nonprofit society, said most of the plants collected in December and January were nonnative cactuses such as golden barrels, Mexican fence posts and Peruvian apples.

They were either sold to support the society’s work or planted at Pima Prickly Park, a 9-acre cactus garden maintained by the county and the society near the west end of River Road.

Shulick said the only native plants rescued — mostly saguaros and native barrel cactuses — were the ones directly in the way of the demolition crews. The rest were left in place as part of the county’s plan to restore the now-vacant land as a natural, desert riparian area.

An empty lot, except for a few palm trees and brick wall, are all that’s left of a home in the 4200 block of East Havasu Road, just east of Columbus Boulevard. The home was one in a flood zone the county bought and leveled.

Jones said a few brick retaining walls were left in place, and some earthwork was done here and there to try to preserve the overall grade of the properties. Workers also laid down a layer of native seeds in hopes of getting some plants to grow where the homes once stood.

Ultimately, officials want to make sure that removing the houses didn’t make the flood situation any worse for the neighboring properties.

“We’ll see what happens. We’ll see if they get some flows this year,” he said.

June 15 marks the official start to the monsoon season, which lasts until the end of September. Forecasters from the National Weather Service and elsewhere are predicting hotter and drier conditions than normal across much of Arizona this summer.

Of course, all it takes is a few downpours in the wrong spots to create problems. As Jones pointed out, 2020 was the second driest monsoon season on record in Tucson, but “we still had flooded houses.”

“A prediction of a dry monsoon doesn’t let us off the hook,” he said. “Even in dry monsoons, there are still significant storms, and those storms cause flooding.”

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean@tucson.com. On Twitter: @RefriedBrean

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean@tucson.com. On Twitter: @RefriedBrean