Technology developed at the University of Arizona can tell just how shaky your hands get when you lie online.

Neuro-ID, a new company founded with technology developed by UA researchers and licensed by the university, aims to stop deception online by probing the intent behind clicks of a computer mouse.

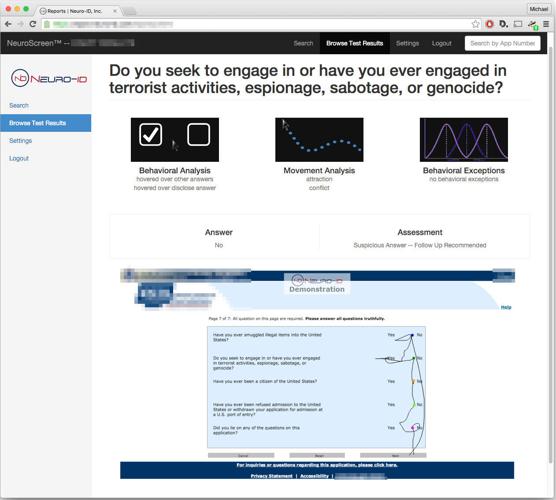

The company’s software tracks users’ computer inputs, such as mouse movement, click accuracy and behavior during questions. It then assigns the user a “suspicion index score” that compares that information to the way he or she answered control questions such as birth date and gender.

“It’s not necessarily that we try to define and say that this person is a liar, because no technology can do that,” said Joe Valacich, founder, chairman and chief science officer at Neuro-ID and professor of management information systems at the UA’s Eller College of Management.

The software, called Neuro-Screen, not only uses control questions to assign a score, it also compares subjects’ behavior to the behavior of more than 7,000 people who tested the product during development.

“When people are in a good mood, they actually get a little faster and more accurate,” Valacich said.

Neuro-Screen has the potential for a wide variety of business and government uses, the company says. For example, a company could use it for its online job applications to spot applicants who might be lying about their qualifications.

An insurance company could use the technology in its claims department to identify claims that might be fraudulent and need a closer look.

The company will first focus on the financial and insurance sectors, Valacich said, noting that employee fraud costs the world economy an estimated $3.5 trillion annually.

“It can be applied to almost any situation where people have some reason to be deceptive,” he said.

Neuro-Screen uses over 250 different measures to determine a user’s score. The software can also break down the analysis by question, so firms can see which answers may not be truthful. If someone hovers over an answer for too long, that question might be flagged.

Neutral algorithms

Neuro-ID’s product works with any computer that has a mouse and a keyboard, but the company is working on cracking the mobile computing market.

The company has already set up basic functionality for its software on phones and tablets but is still trying to improve its accuracy on such devices. One current avenue of research is how a user holds a phone — people who are being deceptive often have stiffer movements and posture, Valacich said.

Unlike other methods to detect deception like a polygraph test, Neuro-ID’s software can be instantly deployed to millions of people at once. It also eliminates any human bias, the company says, because the algorithms are generating the final score.

“It treats everyone the same and lets the data do the talking,” Valacich said.

The technology Neuro-ID employs sounds similar to software used by online advertisers, said Cooper Quintin, a staff technologist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit that advocates for civil liberties online.

“A lot of online advertising companies use (algorithms) to determine if an ad is being clicked on by a human or is being automated in some way,” Quintin said.

However, Quentin worries that any errors in Neuro-ID’s system could create unintended and possibly serious consequences.

“Any system where we are using an algorithm to determine if something is fraud or spam is going to have false positives,” he said. The result would be much more damaging than simply flagging an email as spam.

He also worries that certain people — such as those who use non-traditional input methods because of a disability or people who aren’t confident with computers — might be falsely flagged as behaving suspiciously. He said he hopes Neuro-ID clients would never make decisions based on such data without investigating further.

“There should always be a human in the loop actually looking at these things,” he said.

Becoming reality

Valacich founded the company with his former graduate student Jeff Jenkins, now an assistant professor at Brigham Young University. While Jenkins pursued his doctorate at the UA, the research that would become foundational to Neuro-ID was part of his dissertation.

The pair worked with Tech Launch Arizona, an office within the UA that helps to commercialize university research, to patent the technology while Jenkins was still a graduate student.

“It’s a neat experience to take science and to start materializing it into patents and then businesses,” Jenkins said.

Before the company was formed, Tech Launch Arizona helped the founders identify where their product would be needed in the market. Through the office’s Proof of Concept program, they were able to prototype the software and get feedback from external experts.

The program “provides data that they are able to go and talk to with investors about and use to talk with potential customers,” said David Allen, vice president of Tech Launch Arizona. This data helped Neuro-ID identify potential markets, such as health care and financial-fraud detection.

Michael Byrd, senior vice president of products at Neuro-ID, has years of experience investigating fraud.

As a graduate student at University of Texas at Austin in 2001, he became interested in fraud when he watched it destroy Enron. Ironically, he followed the company’s downfall live on an “Enron-sponsored stock ticker” in the business-school lobby.

Byrd then spent years after earning his master’s degree investigating fraud in the financial sector as an employee of Ernst & Young. While there, he became more interested in the technology he was using to detect fraud.

“Instead of buying and using, I would rather be inventing and selling,” he said.

He decided to attend the UA’s Eller College of Management as a doctoral student to create technology that could solve real-world problems.

“One of the things that drew me here was the degree to which the MIS program emphasizes making things,” he said. “We want to do research and find great ideas, but we want to make things that make a difference.”