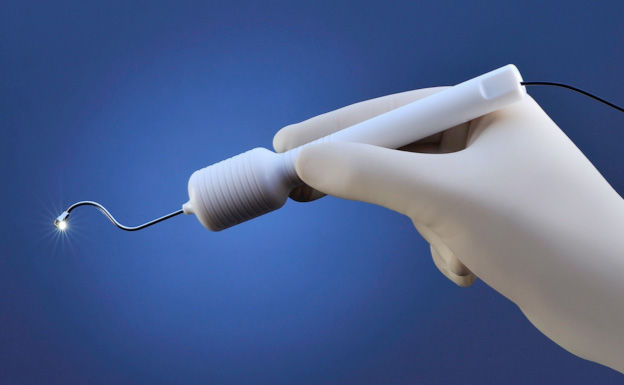

The medical instrument that Tucson-based startup Salutaris Medical Devices is developing can give you the willies, with a hook designed to be inserted behind the eye.

Despite the high yuck factor, Salutaris’ new method for radiation treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration offers new hope for patients with a major cause of age-related blindness.

And some nine years after its founding based on research at the University of Arizona faculty, Salutaris is preparing for its first full clinical trial, after a small earlier study showed promise.

Age-related macular degeneration, or AMD, is an eye disease that progressively destroys the macula — the central portion of the retina at the back of the eye — impairing central vision and leading to partial blindness.

Macular degeneration is the leading cause of legal blindness in people over age 55 in the U.S., affecting more than 11 million individuals, according to the nonprofit Macular Degeneration Association.

There are two types of AMD, dry or atrophic, and wet or neovascular, which accounts for about 10 to 15 percent of all AMD cases — still more than 250,000 new cases each year.

So far, there are no cures for either dry or wet AMD, but the progress of the more aggressive wet AMD has been managed with several drugs approved since the early 2000s that can limit the abnormal blood vessel growth that characterizes the disease.

Despite its looks, Salutaris’ applicator offers patients with wet AMD an alternative treatment that can limit the need for drug injections, said Ryan Lohrenz, who was named CEO of Salutaris earlier this year after serving as the company’s engineering director.

The company’s patented and patent-pending technology consists of a hook-shaped applicator with a light at the end and a cup that holds a tiny disc-shaped pellet containing radioactive strontium.

In a minimally invasive procedure that could be performed on an outpatient basis, the applicator is inserted through a small incision in the eyelid and worked around to the back of the eye, where it is rested outside the macula, an area in the center of the retina.

The whole process takes about 15 minutes in a “one and done” procedure, Lohrenz said.

Lohrenz, a UA engineering alumnus, said he’s used to people shivering when he tells people he meets about what what the company is developing.

“When you think about our device going around the back of the eye, that sounds pretty unpleasant,” he said. “But when you think about getting an injection right into the eye every month, it doesn’t sound so bad.”

Radiation therapy, known as epimacular brachytherapy, has been tried with an applicator inserted through the eye, with mixed results. A study presented at a European conference in 2015 concluded that the procedure did not look promising as a treatment for previously treated wet AMD.

Researchers in England also have been studying a method where radiation is precisely beamed through the front of the eye.

Lohrenz cited a limited feasibility study Salutaris published in 2012, showing that of six patients who received the company’s treatment, two patients required no additional drug injections after two years, and four patients had improved or stabilized vision.

Salutaris rolled out an improved version of its disposable applicator last fall. The company’s first model featured a mechanism that pushed the radioactive pellet through the end of the device once it was in place.

Lohrenz said the applicator is already being produced by a specialty plastics firm in Phoenix, and the company has secured a long-term partner in Boston to supply the specially deigned radioactive pellets.

A full clinical trial is the next step.

Salutaris is preparing a larger clinical trial that is expected to launch in the coming months, Lohrenz said. The company isn’t discussing details of the planned trial because of regulatory concerns.

“We’re looking at how big that will be, planning that up and working on a budget,” he said.

Salutaris, which has raised millions of dollars in private investment, has enough money to proceed with the near-term trial but will be looking to raise more money for later, larger trials, Lohrenz said.

The company got a major partner in 2015, when Japan-based Hoya Group made an undisclosed investment.

Hoya owns 18 percent of the company, the largest single stake, with other investors including members of the local Desert Angels and tech-oriented funds like the Scottsdale-based Translational Accelerator LLC, or TRAC, and Arizona Tech Investors.

“Our very first investors from 2008 were Desert Angels, so thanks to the Tucson community,” said Maryline Boulay, development director for Salutaris.

The company got another boost last year, when it won a $250,000 award in the Arizona Innovation Challenge, which is funded by the Arizona Commerce Authority.

Salutaris has deep ties to the UA, though its original founders are no longer involved in the company’s day-to-day operations.

Salutaris Medical Devices was launched in February 2008 by four co-founders: former UA ophthalmologist Dr. Luca Brigatti; Russell Hamilton, a UA professor of radiation oncology; Dr. Laurence Marsteller, a UA medical school alumnus and entrepreneur and Michael Voevodsky, a UA alum and Harvard MBA who was Salutaris’ CEO for seven years and now heads an advanced manufacturing firm in Michigan.

Marsteller stepped down as CEO earlier this year and is now a consultant to the company. Hamilton is a scientific adviser along with Dr. Reid Schindler, an ophthalmologist and specialist in the treatment of ocular disease with radiation.