Don and Mera Rubell had a key criteria when they started collecting contemporary art in the 1960s.

It had to be interesting.

“The art that ultimately proves most interesting is the art that makes you uncomfortable when you see it,” Don Rubell said at a talk earlier this year at the São Paulo (Brazil) Museum of Modern Art, as reported by Artnews magazine.

Among the interesting — and important — pieces they have collected are works by African-American artists.

This Friday, Oct. 5, the Tucson Museum of Art opens “30 Americans,” art by African-American artists from the Rubell family collection.

The Rubells, who show their expansive collection at the Miami-based Rubell Museum, have a good eye.

They purchased pieces from emerging artists, some who now have international reputations, and pieces by established artists who continue to grow in stature.

“This is some of the most significant art of our time,” Julie Sasse, TMA’s chief curator, says of the exhibit.

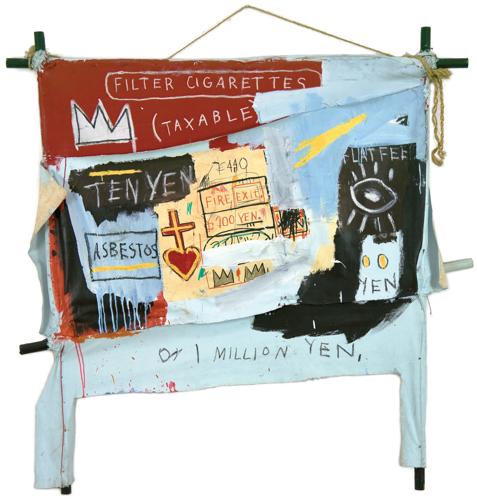

Among them: Kehinde Wiley, who was tapped to do President Barack Obama’s portrait; Robert Colescott, who taught at the University of Arizona and gained an international reputation for his works, which colorfully mock sexual and racial stereotypes; Mark Bradford and William Pope.L, who were listed among artsy.net magazine’s 20 most influential artists of 2017; graffiti artist, poet and painter Jean-Michel Basquiat — a painting by the late artist sold for more than $110 million last year, the most ever paid for a work by an American artist. The list of impressive names go on.

“These are rock stars of the art world,” Sasse said about many of the artists in the traveling exhibit.

“The scale, the quality, the time period of these works — there’s no way (TMA) could put an exhibition of this caliber together. The Rubells are sharing a big gift.”

Here’s a peek at what’s in the show:

Nick Cave

Nick Cave’s “Soundsuit, 2008, synthetic hair, fiberglass and metal, 98” by 27” by 14”

“Soundsuit,” 2008, synthetic hair, fiberglass and metal

Cave is an Alvin Ailey-trained dancer whose art often echoes the grace of dance.

His “Soundsuit,” a series of 8-feet tall wearable and outrageous sculptures, has brought him plenty of buzz.

“This sculptural form is based on the scale of my body,” Cave says in the catalog of the show. “It creates a camouflage, masking and forming a second skin that conceals race, gender and class, forcing one to look without judgment.”

And to be in awe.

Said a New York Times review of the “Soundsuit”: “Whether Nick Cave’s efforts qualify as fashion, body art or sculpture, and almost regardless of what you ultimately think of them, they fall squarely under the heading of Must Be Seen to Be Believed.”

The elaborate suits are actually designed to be worn by dancers, and they make a musical sound as they move.

Xaviera Simmons

In “One Day and Back Then (Standing),” Xaviera Simmons transforms herself into a different character.

“One Day and Back Then (Standing),” 2007, Chromira C-print

Simmons transforms herself into different characters for her photographs. Here, she is in black face, dressed in black, and standing in the midst of golden reeds as she looks directly at the camera, proud and defiant. It’s jarring and provocative. Her work often demands we rethink what we understand about memory, time, politics and landscape. “When I see this,” TMA’s Sasse says, “I think she’s saying ‘this is how you see us.’ ”

Rashid Johnson

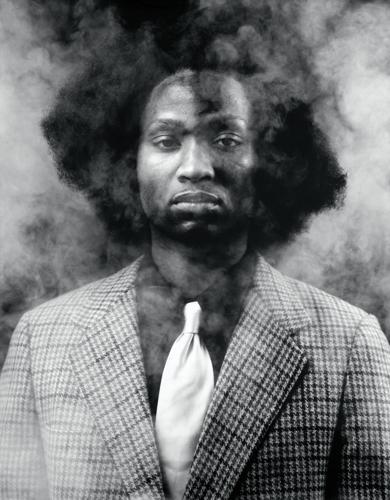

“The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club (Thurgood)” by Rashid Johnson is part of series of Lambda prints.

“The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club (Thurgood),” 2008, Lamda print

Forbes magazine has called Johnson “one of the four or five most important contemporary American artists.” This piece is one in a series about the members of a fictional club. “Thurgood” is a reference to Thurgood Marshall, the first African-American to sit on the Supreme Court.

Johnson developed this series after learning about a club founded in 1904 at a black university. “I thought it was an interesting moment to talk about the black upper class and how they had developed these clubs in order to help each other,” Johnson said in an interview with ArtPulse magazine.

“… I wanted to frame that group in a poetic sense with these portraits, as well as leave a lot of open-ended space to interpret how they might participate with one another. We are not given any information as to how the club works, what their ceremonies or rituals are. All we see are the members.”

Mickalene Thomas

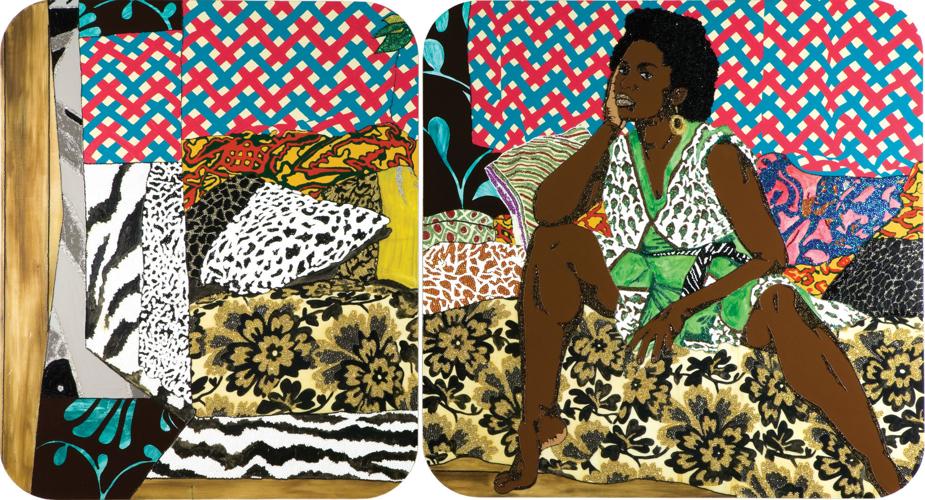

Mickalene Thomas reimagines images from the 1970s, when black power and feminism were on the rise. “Baby I Am Ready Now” is a 2007 diptych in acrylic, rhinestone and enamel.

“Baby I Am Ready Now,” 2007, acrylic, rhinestone and enamel on wood panel

Thomas, called a “renaissance rock star” by Smithsonian magazine, reimagines images from the 1970s, when black power and feminism were on the rise. “The late ’60s and ’70s for me is a particular space for black women and black people where they were really sort of defining themselves,” she said in an NPR interview.

“Defining themselves and their place in the world culturally, artistically, how they feel about their own sense of identity. With mantras and slogans — ‘We’re black and we’re proud.’ This forging their foundation, saying, ‘Look at us, we’re here, this is our validation.’ ”

Her influence is clear in this diptych: the women on the right is cool, composed, direct. On the left, the interior without the anchor of the woman explodes into abstraction.

Kehinde Wiley

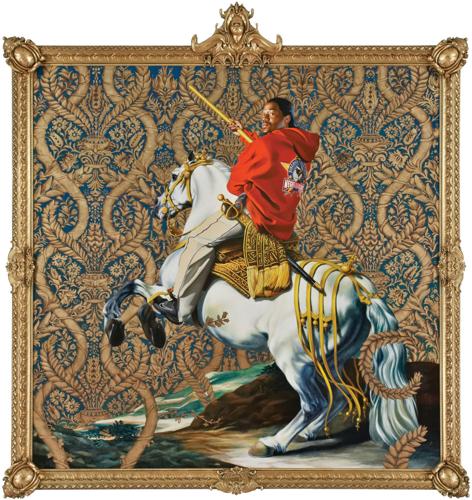

Kehinde Wiley’s “Equestrian Portrait of the Count-Duke Olivares” is based on a Diego Velázquez painting of the same name.

“Equestrian Portrait of the Count-Duke Olivares,” 2005, oil on canvas

Wiley, the artist behind President Barack Obama’s portrait, calls on the Old Masters and inserts a black subject — often someone he finds on the street — to transform the story. This image is based on a Diego Velázquez painting of the same name. The rearing horse is under control in the rider’s hands, the sword, indicative of nobility, and the baton, which implies the subject’s leadership skills, are all found in the Velázquez painting. Portraits like the original Velázquez were intended to convey the subject’s social status, power and wealth. By replacing Olivares with a young black man dressed in a hoodie and baggy pants, those traits are transferred to him.