Sara Bruner is intense.

The director of Arizona Theatre Company’s production of the musical “Cabaret,” is huddled together with Sean Patrick Doyle, who plays the Emcee, and Madison Micucci, who is the cabaret singer Sally Bowles. They are a little more than a week into rehearsals and these are the only two actors in the room.

They are deep in conversation as they try to work on a key scene, with Sally and the Emcee both on stage but not interacting.

They talk about the text, the emotions, the movements. Just as they are about to break into the scene, Bruner says “The entanglement theory! Have you heard of the entanglement theory?” and she heads back to the huddle.

The quantum physics theory holds that the actions of one can impact the other. It’s a perfect visual for what they are trying to do in the scene.

And it gives Micucci and Doyle what they need to make it work.

Talk is essential to what Bruner is doing.

“When the text is so rich and written so well, there are so many things you can talk about,” she says in an interview a few days later. “There is not just one way you can play Sally or the Emcee.”

“Cabaret” has been around since 1966, first as a play with Joel Grey playing the Emcee, and most recently on Broadway, in 2014, when Alan Cumming created a more sinister Emcee (that was a remounting of the 1998 revival).

Doyle is not planning to do Grey or Cumming. He’s going to do Doyle.

The trick, he says, is “how to reinvent a piece that is so burned in people’s minds, and to find where there is room for innovation.”

And he thinks the road to that is to hold on to the character’s human aspect.

“I would like to portray someone who succeeds at the provocative dancing, the satire, but underneath is a person who is empathetic and affected by it.”

And he and all the actors keep what Bruner said at the very first rehearsal: “We are not here to recreate. We are here to create.”

“My hope is that people do not come to see a play recreated,” she says. “I should not be recreating the memory of a show people have seen.”

Bruner is in good company: A reshaping of the musical has been a constant since that first Broadway production. Songs were added and taken away. The bawdiness evolved. The sexuality of its characters became more fluid.

The 1972 movie, directed by Bob Fosse and staring Grey and Liza Minnelli, was rewritten to more closely follow the source material, Christopher Isherwood’s somewhat-autobiographical novel, “Goodbye to Berlin.”

When Director Harold Prince, who helmed the original, remounted it on Broadway in 1987, it was again tweaked. Director Sam Mendes totally reimagined it for the 1998 Broadway production starring Cumming — the same production was remounted in 2014.

There are actually three versions of the performing script available, which is almost unheard of. According to Playbill, the only other piece with multiple versions is Leonard Bernstein’s “Candide.”

“It has changed more than any other play,” says Bruner.

She wants to make sure her production is marked by the hearts and souls of the characters populating the musical.

“I have some whip-smart actors,” she says. “They did their research. They want to mine their characters’ humanity.”

“We never lose the human aspect,” says Doyle. “The numbers are big and lavish, but you have to keep the human in mind.”

There’s something else to keep in mind: The story is about Berlin just as Hitler was coming to power. There was a willful ignorance about what was happening to the country. Many believe that ignorance echoes in this country today.

Chanel Bragg smirks as Madison Micucci who plays Sally Bowles in the Arizona Theatre Company’s production of “Cabaret” runs through lines during a read through of the show, on Nov. 5, 2019.

“What I really appreciate about Sara’s version is it ... suggests an urgency and a call to action and asks the audience to look at themselves in the mirror,” says Micucci. “Without going to the obvious place, I think it’s begging the question ‘what would you do and how would you behave?’ This is an example of how inaction can potentially lead to something.”

Doyle agrees that though more than 50 years old, the play smacks with relevance.

“We are in a stage where we are flirting with fascism,” he says. “The undermining of the press, creating enemies, capture-and-release scare tactics — these are signs. … ‘Cabaret’ is a good reminder to audiences that apoliticism and apathy are not helpful and have a cost.”

Sean Patrick Doyle, who plays Emcee, left, and director Sara Bruner talk about a scene during a “Cabaret” rehearsal.

Jaclyn Miller, choreographer, shows her dancers some movements for the musical “Cabaret.”

Madison Micucci, right, who plays Sally Bowles, looks over at Sean Patrick Doyle, the Emcee, as the two act out a scene.

The “Cabaret” actors get into character during a read through of the show.

Shaun-Avery Williams, far right, holds a pose during a rehearsal of “Cabaret,” which hit Broadway in 1966.

From left to right, Spence Ford, Tatumn Zale, Alex Caldwell and Lisa Kuhnen work on their routines.

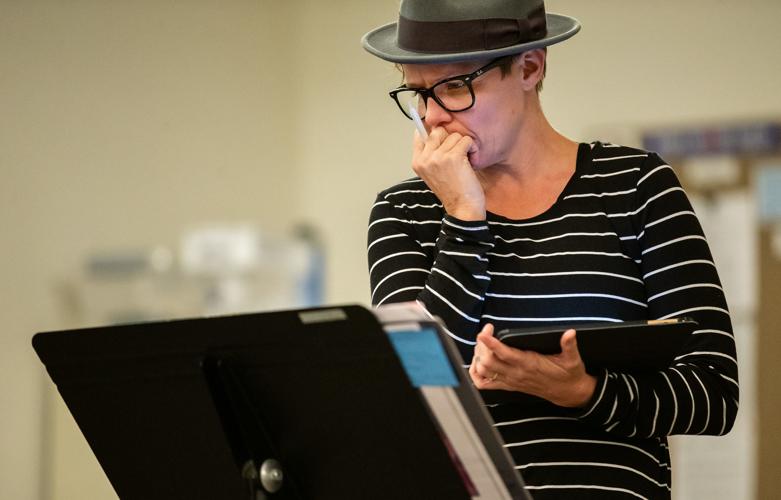

Sara Bruner, who is directing the Arizona Theatre Company’s upcoming performance of “Cabaret,” looks over the show’s script during a read through, on Nov. 5, 2019.