Progress is not easy.

It can be bloody. It can be cruel.

And, yes, it can be glorious.

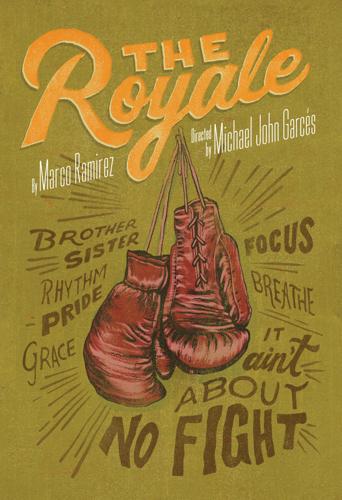

Progress is at the heart of “The Royale,” Arizona Theatre Company’s painful — and glorious — season opener.

It is loosely based on the boxer Jack Johnson, a black man who, in the early 1900s, had the nerve to climb into the ring with a white man in hopes of proving he was the champion of the world, not just the black world. These were in the Jim Crow days, when lynchings were common and racism ruled. The white world was outraged.

Marco Ramirez’s rhythmic and tense play, economically and gracefully directed by Michael John Garcés, tells the story of Jay “The Sport” Jackson, who has gained fame and the title of “Negro Heavyweight Champion of the World.” It opens with a boxing match between Jackson and Fish, a young amateur boxer. They both throw ferocious punches, though they never make contact.

That’s part of the beauty of this stylized play: they move as though they’ve been punched, wince as though they hurt, but the blows are in the choreography, the words and the precise clapping and stomping of the cast.

Jay wants, insists, that his white manager persuade the reigning world champion to come out of retirement and fight him so he has a chance to gain the title he deeply feels he deserves.

But no black man has ever climbed into the ring with a white man.

And the prospect, it turns out, is a dangerous one.

This play, is, of course, about much more than boxing.

It is also about the need, the thirst, the demand, for equality. And it is about the cost of getting that.

The Misha Kachman-designed set, spare with just a boxing ring, a punching bag and a bell, had an eloquence, and Allen Willner’s lighting, sometimes harsh, at other times more gentle, beautifully punctuated moments.

This is a pristine cast, led by Bechir Sylvain as Jay, big, powerful and a man with a deep longing to make the world right for those who look like him. Sylvain is a master of subtext — he makes his pain, his hunger, palpable without ever overdoing it. He was a magical presence.

Roberto Antonio Martin is Fish, the boxer who challenges Jay and then becomes his sparring partner. That opening sequence — the fight between Fish and Jay — is remarkable to watch: his face changes, almost seems swollen and bloody, his legs weaken, as the match wears on.

Martin made that fight scene and Fish’s exuberance for the sport and working with Jay shimmer.

Peter Howard skillfully portrays Jay’s often-frustrated white promoter and manager as well as a slew of reporters who throw questions at the boxer. Erica Chamblee is Nina, Jay’s sister.

She doesn’t speak until late in the play, but is a shadowy presence throughout, a poignant symbol of what drives Jay and what he could lose.

Nina’s pride at what her brother has accomplished, and her indignation that the cost has spilled out over her family and others with skin like theirs, are powerful in Chamblee’s hands.

Edwin Lee Gibson’s Wynton, Jay’s trainer, is a wizened and wise presence.

What he has lived, what he has endured and his determination, are clear in Gibson’s face, his walk, his voice.

And there is one remarkable scene that brings Gibson to center stage. He stands there and for the longest time, alone and silent, he slowly looks over the audience.

His face is a mixture of resentment and sadness, his eyes packed with ache and accusation. There is no doubt: we were culpable, we wielded the knives, tied the ropes, tolerated inequality. Our silence, inaction, equals guilt. It’s an extraordinarily powerful moment. And it brings this story that takes place more than a century ago right into modern times.