You will be able to spot Ted Warmbrand in the crowd next Sunday at the Little Chapel of All Nations.

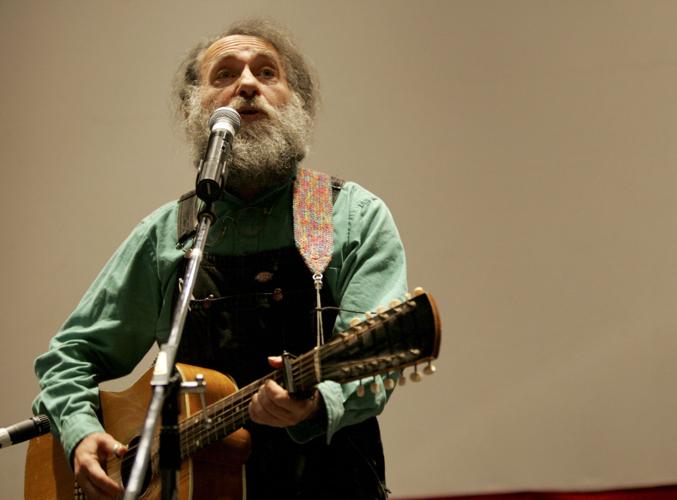

He’ll be the one with the head of unruly nearly all-white hair, thinned high on his forehead, and a bushy white beard that dips nearly chest level.

He might lean in a bit when you talk to him so he can hear you better. He’s being fitted for hearing aids after noticing recently that sometimes he mistakes what people are saying.

But he has no trouble hearing when people sing. Songs have always been his preferred way to communicate, especially when the topic tends to be controversial.

“I believe in the power of singing songs,” said Warmbrand, 73, who was voted in 1991 by Tucson Weekly as the Best Local Eccentric — a category the paper later eliminated from its annual best-of polling. “I try not to get into arguments and argue a point, but if I can sing them” people might be more inclined to listen.

At his song circle on Aug. 7, he will return to a familiar topic, the nuclear age. He’s been singing out against nuclear power and its dangers since the early 1970s, not long after a chance meeting with activist John “Skip” Laitner, a man who had the ear of powerful consumer advocate and political activist Ralph Nader. Laitner and Nader were going around the country warning of the dangers tied to generating electricity by splitting atoms.

Warmbrand recalled that he was living out of his car at the time, traveling around the country singing his songs wherever he could and collecting songs of other singers along his travels.

“I remember standing in a restaurant with my stomach growling waiting to see if I could sing for a meal,” recalled Warmbrand, who was a KXCI radio host for 17 years and has promoted concerts with his nonprofit Itzaboutime Productions for years in Tucson.

But the argument against nuclear power struck a nerve like no other issue he had tackled. And he had tackled plenty, from the mistreatment of migrant workers and immigrants to advocating for the downtrodden displaced by political or economic circumstance.

Warmbrand learned to sing when he was growing up in the Bronx, New York, listening to old phonograph records and scrounging through songbooks. His parents occasionally sang in their apartment; Dad sang happy songs and Mom leaned more on the sad side.

As a kid, Warmbrand turned to music to get through everyday life. Whenever he couldn’t find a song that fit his mood, he wrote one.

“I admit I always liked songs that bravely or bluntly faced ‘ealities’,” he said. “Honest” music best expressed in folk songs.

“I even loved the Gilbert and Sullivan operas Linda Ronstadt mentioned her mother liked,” he confessed. “Art that helped us peek behind the mask of social mores to some extent, not to destroy them, or abandon them, but to grow from and delight in the act of artful probing.”

Warmbrand doesn’t call his music protest songs. He’s not protesting as much as advocating a different opinion. Protest songs urge listeners to “feel bitter, not better”; they get to vent, but not act, he said. His songs encourage change.

“I try to sing and make honor songs for those who may be willing to swim against the tide for something greater than themselves,” he explained. “And songs to provide example for those who are not yet convinced they have it in them to honor their most generous instincts.”

Warmbrand started singing those songs at early United Farm Workers boycotts in the 1960s and took up the cause of Central American refugees and the Sanctuary Movement, following his wife’s lead. When Humane Borders was formed in the early 2000s, he penned the group’s anthem, “Take Me to the Border,” which is still sung today.

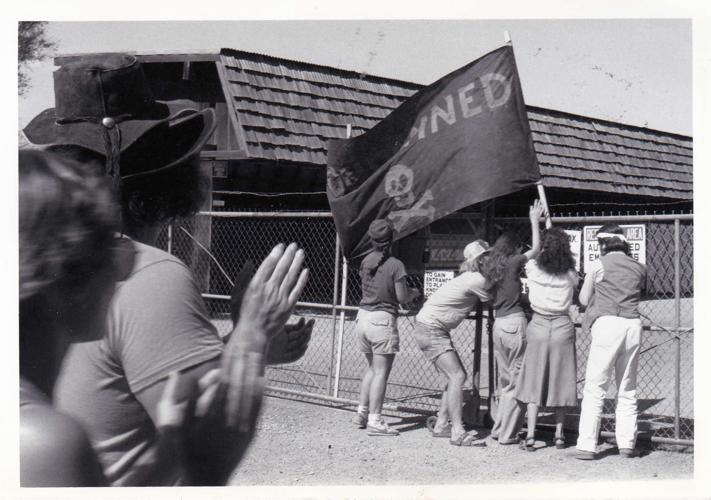

But the nuclear age of the early 1970s posed the biggest threat of any issue he had taken on. It defied geographic, racial and socioeconomic borders because it relied on the same technology that proved deadly to the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan at the end of World War II in 1945; the first atomic bomb was dropped over Hiroshima on Aug. 6 that year.

Warmbrand and others of his generation couldn’t erase those pictures of the mushroom clouds over those cities. And in the 1970s the rush was on to convert that same technology into powering America’s electric plants and, in turn, homes and businesses.

But Warmbrand and others worried that the technology had dangerous side effects, including uranium leaks and the potential for mishaps that could lead to explosions and all manner of unnatural man-made disasters.

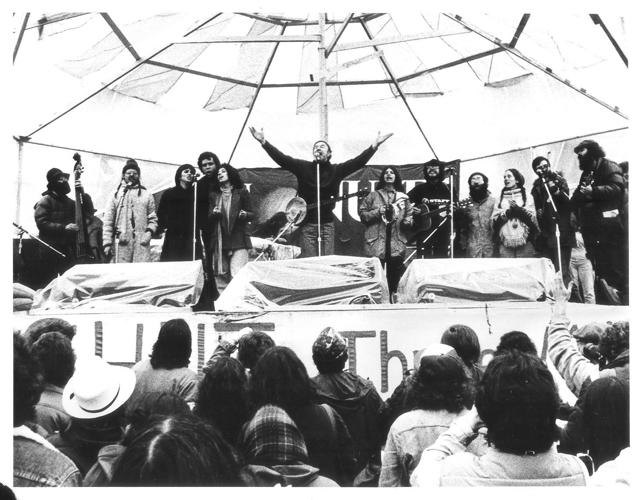

Warmbrand joined Laitner’s effort and was quickly anointed the resident songbird. Every good movement, after all, needs a song, and Warmbrand was not only regarded as a pretty capable vocalist and songwriter, but as a gifted song collector, the person who hears a good tune and takes it to his audiences.

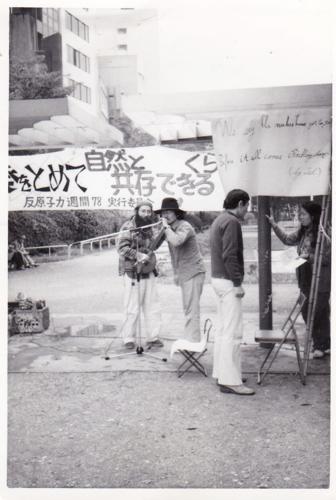

In 1977, Warmbrand joined a group of survivors of the Japanese attacks who were in the U.S. visiting American nuclear plants, including Arizona’s Palo Verde Nuclear Power Plant near Buckeye. Warmbrand persuaded the group to make a side trip to Tucson. On the ride home, he sang some upbeat anti-nuclear songs and the Japanese group was so impressed they invited him to come home with them. He made the trip to Japan the following year and spent a month there, joining protest marches, visiting significant landmarks where the bombs did their biggest damage, and performing for and alongside survivors.

“In Japan, the group that I was around, every time they tested a nuclear weapon they went to the (courts) and sang protest songs,” he recalled.

At a performance in Hiroshima, Warmbrand saw American folkie great Pete Seeger. Warmbrand sang the nursery rhyme “I’m A Little Teapot,” but he subbed “We better watch out for the trouble / They are brewing for us” for the refrain “When I get all steamed up I just shout / Tip me over and pour me out.”

He also was invited to an apartment of a Hiroshima survivor who was a child during the bombing. She had burn scars over her body from the blast. When Warmbrand arrived at the home, he was greeted by a roomful of little kids, so he sang a Japanese nursery rhyme he had collected in his Japan travels.

At the end of his month in Japan, Warmbrand came home and was anxious to share his experiences.

But his words fell on deaf ears.

“Nobody gave a damn pretty much,” he recalled. “I was so depressed. I had all this excitement in me and they were like, ‘So what.’”

But the Japanese were listening. A collection of his songs was published in the Japanese songbook “Love Songs of the Nuclear Archipelago.” Warmbrand still has a copy.

At his song circle on Aug. 7 — one of several he holds throughout the year as a way to give a voice to folks reluctant to speak up — Warmbrand will pull out those 1970s songs to commemorate the 38th anniversary of his Japan trip. He’ll sing his self-penned “Why Get So Excited,” his reaction to a University of Arizona nuclear proponent trying to explain away how much natural radiation is already in the atmosphere.

He’ll also mix in a few of his other songs, all perfect vehicles for sing-alongs.

“I know what it’s like to be in a big crowd and to be singing together and we sound good,” he said. “It can inspire us to keep going.”

And it can inspire folks to speak out on issues about which they feel strongly but may be reluctant to say anything.

“Music can make you braver,” he said.