These days nerds are hip; artists hipper.

Combine the two, as the University of Arizona College of Science is doing for this year’s Tucson Festival of Books, and you create a hipster paradise — the Science in Art neighborhood of the festival’s Science City.

Science City came into being during a public-relations boomlet that sought to brand Tucson with a new logo.

That didn’t quite pan out, but Science City has become a popular destination on the UA Mall during the book festival — a place where you can hold a brain in your hand, see where they make the world’s largest telescope mirrors or pet some Sonoran Desert critters.

The new, artsy neighborhood takes note of a trend in scientific inquiry that mates writers, poets and artists with scientists to produce an artful way of presenting scientific thought, or a scientific approach to art.

The UA Museum of Art explores the chemistry of making paint and pigments from minerals, while the mathematics department demonstrates the sound-wave science behind musical instruments.

Astronomers and planetary scientists will display real and imagined scenes of the cosmos.

It’s a new neighborhood, but actually an old pairing. Scientists have always used artistic techniques to visualize and explain things. Artists have always used math, chemistry and technology to create new methods of conveying artistic truth.

A couple of books whose authors will be presenting on the Science City stage on the weekend of March 12-13 illustrate that marriage of literature, art and science.

“The Sonoran Desert,” edited by Eric Magrane and Christopher Cokinos, is subtitled “A Literary Field Guide.”

Which raises the question: “What the heck is a literary field guide?”

Cokinos, who directs the creative writing program at the University of Arizona, is a poet and author whose books often explore scientific topics.

He said this book began with a scientific endeavor — the 2011 BioBlitz at Saguaro National Park, which enlisted scores of Tucsonans in an effort to document the many species of flora and fauna that create the Sonoran Desert ecosystem.

Eighty writers and artists went along to provide a poetic inventory of the park. Their output begat a website and the idea of publishing a book.

“Give most of the credit to (co-editor) Eric Magrane. He was the driving force behind the project,” said Cokinos. Magrane is a poet and geographer at the UA, where he is a graduate research associate with the Institute of the Environment.

Cokinos and Magrane brainstormed concepts for publication in the library at the former Desert Botanical Laboratory on Tumamoc Hill. “It was clear just an anthology wouldn’t do it,” Cokinos said.

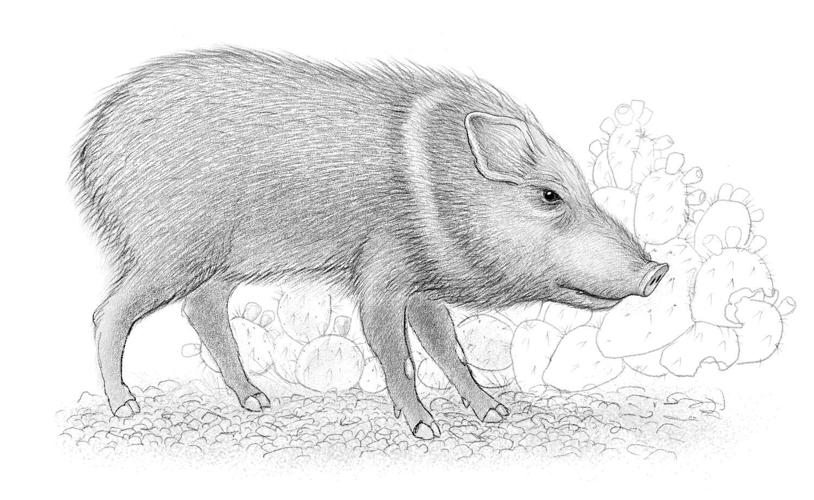

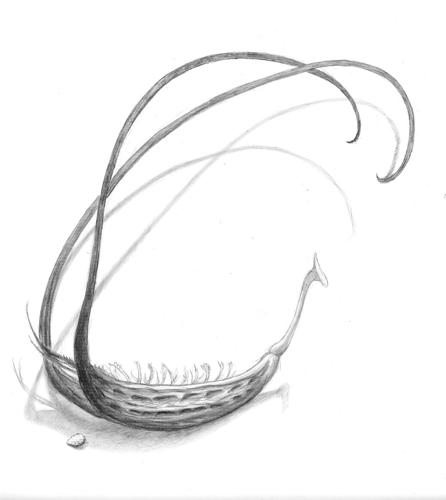

A field guide that introduces readers to 64 of the Sonoran Desert’s prominent and interesting denizens began to take shape.

The editors commissioned some pieces from artists who didn’t take part in the Bio Blitz, filling in some important categories and introducing more “voices” from a new generation of Sonoran Desert writer/naturalists.

“The thing Eric and I were thinking about was the need to establish that there are a number of voices in the desert right now. People tend to think of it as ‘Ed Abbey country’ or ‘Barbara Kingsolver,’ but there a number of others out there.”

So add to the list celebrated poet Alison Hawthorne Deming, whose poem asks questions of the signature saguaro.

If it takes you a hundred years

to grow your first arm

for how long do you feel

the sensation of

craving something new?

And Erec Toso, who writes an ode to jojoba that asks another:

How many whales swim free

because of your gifts of golden oils?

Even the short field guides that accompany each entry of plant, bird or mammal, are questioning at times.

Magrane and Cokinos compiled and vetted the field guide entries on habitat, description and life history from authoritative sources, but could not resist the urge to muse.

On the Gambel’s quail: “Why would a bird develop such a plume on its head? Why would a bird choose to walk instead of fly?”

The field guides aspire to accuracy, not pomposity. “We wanted the natural history sections to be as well-written, as open and playful, and as accurate, of course, as the other pieces.”

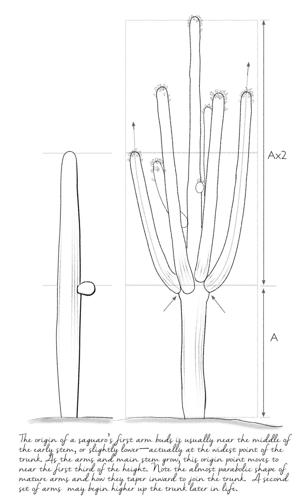

Cokinos said he decided to write the saguaro section of the guide because he has trouble appreciating the ungainly cactus on anything more than an intellectual level, thinking “the more you know, the lovelier something can become.”

That “knowing” can come from more than scientific inquiry.

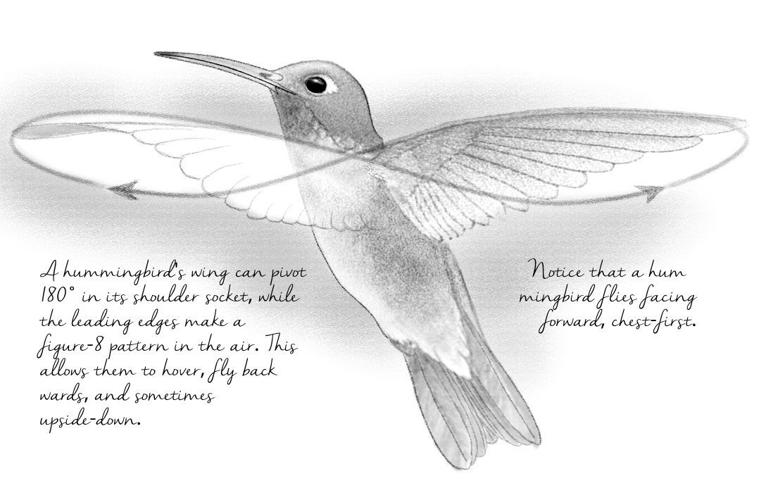

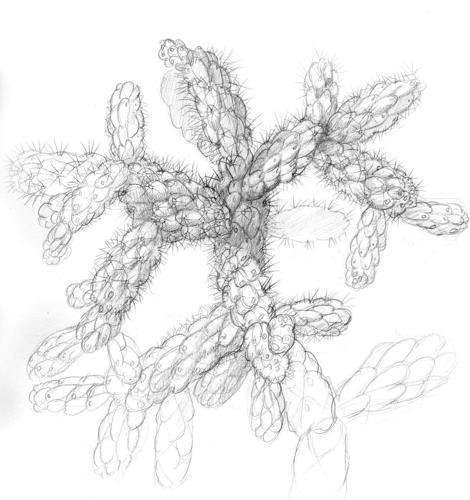

In his “Illustrator’s Note,” Paul Mirocha, whose pencil drawings illustrate each entry, said “drawing is a way of seeing,” a kind of scientific inquiry of its own.

His saguaro drawing explores the proportionality of the gigantic cactus and his sketch of a pouncing mountain lion examines the physiology of its powerful leap.

There is science in art; art in science; loveliness in knowledge.

Under Desert Skies

Planetary scientists were, for a time, considered a bit myopic, studying the dull, nearby bodies of the solar system while their astronomer colleagues peered more deeply into the cosmos.

That changed when President Kennedy announced the plan for America to go to the moon.

Suddenly, the engineering and scientific energy of American scientists was harnessed to exploration of the solar system, and the man best positioned to take advantage of that direction was Gerard Kuiper, an astronomer at the University of Chicago’s Yerkes Observatory.

Kuiper chose the campus of the University of Arizona as home base for his lunar project, where he would help create a field that combined astronomy with geology, chemistry, atmospheric sciences and multiple other disciplines.

“He was Mr. Planetary Scientist,” astronomer Stephen Larson says in the book. “He was about the only one carrying the banner at the time.”

Kuiper, with funding from the new National Aeronautics and Space Administration, created the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, which played a key role in those early moon missions and has participated in every planetary exploration NASA has conducted over the decades since.

Melissa Sevigny, in “Under Desert Skies,” takes us through those years and into the present day, with LPL now leading its second robotic mission into space for NASA. OSIRIS-Rex lifts off from Cape Canaveral six months from now to travel to the Asteroid Belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter, where it will gather a pristine sample of rock to return to Earth.

Sevigny didn’t set out to write a book about the Lab.

She was an undergraduate intern at LPL when its former director, the late Mike Drake, asked her to preserve the memories of LPL scientists who worked with Kuiper to establish the lab.

Her favorite was Ewen Whitaker, lured by Kuiper from England to help create an atlas of the lunar surface, critical for planning the moon missions.

Whitaker, Kuiper and crew were also able to convince NASA, through repeated observations and chemical analysis of the moon’s surface, that its lander would not sink its struts into the deep, sandy soil as other scientists claimed it would.

“I love the old stories about how they didn’t even know what the moon was made of — crazy stories that seem old-fashioned to us now. But that’s science. We’re always in that stage where there’s going to be something out there we don’t know,” Sevigny said.

Sevigny said she wanted the book to preserve the personality of the characters and the stories they told her, in addition to the continual mission of discovery that is the scientific world.

She details the personalities and progress through the decades. The founding of an academic department of planetary sciences and the parade of involvement in NASA missions that turned points of light, one-by-one, into geologic landscapes.

Sevigny, whose major fields of study at the UA were creative writing and geology, was able to be part of one of the UA’s significant contributions to planetary science — the Phoenix Mars Lander mission — the first NASA mission led by a university rather than a NASA-sponsored center.

She attributes her interest in space to participation in the regional science fair as a high school student.

“I’d always thought, as a child, that I was going to be a geologist. At age 14, I went to a science fair and two things happened: I won an asteroid and a trip to an astronomy camp in Hawaii.”

She continued to enter science fairs every year, focusing on Mars. In her junior year, one of the judges, Pat Woida, was a member of the Phoenix Mars Lander team. “He was impressed and invited me to join his team.”

She worked as a volunteer, pursued her education, and returned to the Phoenix mission as a member of the public outreach team during its five months on the Martian surface.

She now works as a science reporter at KNAU, the National Public Radio station on the campus of Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff.

Her work at LPL combined with her journalistic bent to give her an “insider/outsider point of view,” she said.

“I look at it through the eyes of a science communicator,” she said.

“I use a technique called ‘black box.’ You listen to them explain, ‘So this technique does this, but we’re not gonna explain how it works, we’re just gonna move on with the story.’”

“I wanted it to be a character-driven story and have all these big arcs about how science gets done — starting with knowing nothing.”