“Haunted Bisbee” (Haunted America Series)

By Francine Powers. The History Press. $21.99; $12.99 Kindle.

With its rich and somewhat checkered history steeped in Western lore, it’s not a stretch to assume that the Southern Arizona town of Bisbee might harbor a ghost story or two. The sheer abundance of paranormal goings-on in the old mining settlement, however, is startling. Bisbee is one of the “most haunted towns in America,” says Francine Powers, who runs historical haunted tours there. She is qualified to make this case: the journalist, author, and historian had her first paranormal experience at age 6 — instigated by the mishandling of a Ouija board — that required intercession by a Catholic priest. She became a spiritual medium at 14, has penned numerous articles about haunted sites, and is a frequent guest on radio and television. In “Haunted Bisbee” she provides a historic overview that gives context to her reporting on hauntings, visions, and restless ghosts in locations in and around the city. As a journalist, says Powers, she’s a stickler for facts and gives little credence to accounts of paranormal activity that she can’t verify. As a result, this is no tall tale about things that go bump in the night: an eerie, historically supported read is guaranteed. Powers, whose roots go back a long way in Bisbee, recently relocated to Tucson. She is also the author of “Mi Reina: Don’t be Afraid.”

— Helene Woodhams

“A Marriage Out West: Theresa and Frank Russell’s Explorations in Arizona, 1900–1903”

By Theresa Russell, Nancy J. Parezo, and Don D. Fowler. University of Arizona Press. $100 hardcover, $35 paperback and digital.

They called it their “busman’s honeymoon.” Two days after their July 3, 1900, wedding, Frank and Theresa Russell arrived in Gallup, New Mexico, to begin married life. It wasn’t the romance of the Southwest that attracted them; they were driven by the imperative to investigate sites that would support Harvard anthropologist Frank’s research in a climate salubrious to his chronic tuberculosis. For Theresa it was hardly a lovers’ idyll. The educator and would-be author was no outdoorswoman, but over the four-year course of their forays into the Arizona territory she learned to drive wagons, participate in digs, and assess cultural preservation needs, becoming a model anthropologist’s assistant. Viewing her role through the lens of a philosopher with an eye toward her own ambitions, she kept detailed field journals that served as the basis for “In Pursuit of a Graveyard: Being the Trail of an Archaeological Wedding Journey,” a 12-part serial she wrote for Out West magazine. The series, written with charm and wit and replete with classical illusions, underscored her scholarly credentials, and also served as a memorial to her archaeologist husband — who succumbed to tuberculosis in 1903 — and their tragically brief marriage.

This impressive, multilayered volume is more than a thoroughly researched biography of two intellectually gifted and uniquely determined individuals who had the good fortune to find each other, however briefly. Authors Parezo and Fowler also take a deep dive into the mechanics of field research and the overall state of archaeology as a nascent science at the turn of the last century. And, importantly, they provide context for the Russells’ field notes and Theresa’s own writings, which encompass half the book. A captivating read for those with an interest in a unique perspective on Arizona territorial history.

— Helene Woodhams

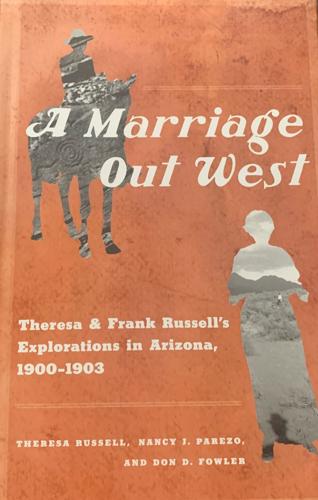

“The Nature of Desert Nature” (Southwest Center Series)

Edited by Gary Paul Nabhan. University of Arizona Press. $16.95, print and digital.

Coming to terms with the desert is not a rational process, says Gary Nabhan. Rather, it’s an imaginative exercise that involves solving riddles, reflecting on paradoxes, and expunging hackneyed descriptors like “desolate” and “empty” from your desert vocabulary. For too long, desert regions have been characterized as nonproductive wastelands, observes the plant conservationist, desert ecologist, nature writer and Ecumenical Franciscan brother. But, a fresher, nondualistic approach is emerging in the arts and sciences, and this is the good news that Nabhan celebrates with this essential book of essays contributed by authors who write, from myriad perspectives, about their appreciation for the rich fullness of the place.

Nabhan begins by taking on a few paradoxes and describing some verified cases of enchantment in a “deep history” of the desert’s prickly nature, punctuated with anecdotes drawn from his extensive arid land experience. It’s a thought-provoking, scientifically grounded exposition that encourages readers to look again, using “Zen eyes,” while gently reminding us that historically, the desert has been defined by people only capable of recognizing what it lacked, and not what it offered. With the stage set, the essays follow, divided into sections authored by Indigenous people, contemplatives, longtime desert dwellers, recent arrivals, and those who know it as contested ground. The final section, containing essays written by artists, includes several four-color reproductions of Tucson murals. If you think you know the desert, think again. As this captivating collection ably demonstrates, there’s so much more here than meets the eye.

— Helene Woodhams

“The Amorous Adventures of Charlie Meyer: A Novel of the Sixties”

By Arthur D. Hittner. Apple Ridge Press. $16.95 paperback.

Arthur D. Hittner doesn’t dawdle unveiling the central theme of this rambunctious novel: In the opening scene, sitting at a picnic table with his first girlfriend, Susie Sadowski, 6-year-old Charlie Ulysses Meyer stealthily runs his hand down the front of her bright red shorts. Eureka! Charlie’s discovered gender difference. He will turn that discovery into a focused study.

This is retired attorney Hittner’s seventh published book — four nonfiction and three previous novels — which primarily relate somewhat seriously with art and/or baseball. In his preface, Hittner writes that “The Amorous Adventures …” was, in fact, the first book he wrote. Since it was loosely informed by his and friends’ experiences, he debated releasing it, but says he’d leave it to readers to judge its relative merits.

The action follows Charlie from his New Jersey childhood through college in New Hampshire (New Jersey-raised Hittner went to Dartmouth). Much of the action ends up being various attempts to deepen the Susie Sadowski red-shorts revelation … with a couple of manhood-threatening misadventures thrown in. The book’s light. It’s not politically correct, but it’s entertaining. It’s a species of period piece — the late 1960s, with the draft and Vietnam hovering, the Summer of Love fading. Charlie, though, is an appealing character, a romantic who naively confuses lust with love, and finds himself living every college boy’s dream — choosing among the four girls he’s bedding.

So… does this Hittner book measure up to his others? Sure; why not? It presents another facet of Hittner’s oeuvre. It offers a bit of insight into the nature of relationships. Its perspective might be enlightening to the Susie Sadowskis of the world. And, yes, it’s likely, as he admits, “to embarrass [his] children and grandchildren.”

— Christine Wald-Hopkins

“A Desert Feast: Celebrating Tucson’s Culinary Heritage”

By Carolyn Niethammer, with foreword by Jonathon Mabry. University of Arizona Press. $19.95 paperback.

“Our city doesn’t taste like anywhere else,” writes Carolyn Niethammer quoting archaeologist and Tucson City of Gastronomy Director Jonathon Mabry. “It’s a combination of recipes and ingredients from a long and complex culture.” Indeed, this comprehensive, tastefully illustrated text is a testimonial to the richness, diversity and history of the food culture of Tucson, UNESCO’s first City of Gastronomy. In the book, longtime food writer Niethammer takes an expansive, historical view (4,000 years of occupation) of native traditional foods and means of preparation — and folds in European, Mexican and Chinese contributions. She offers desert gardening tips, resurrects heritage fruits and vegetables; highlights small-scale commercial agriculture, local artisan food producers; and discusses food justice. Extensively researched, this work includes photographs, recipes and an epilogue addressing Tucson’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Niethammer reminds us how fragile and significant food production is and underscores the importance of supporting its local purveyors.

— Christine Wald-Hopkins

“Jiggling: A Gradual Release”

By Eugene Lowe. Self-published via Amazon. $8 paperback.

According to the cover of this memoir, “jiggling is a dancing to the music; it is sometimes an altered state; it is a picking up of whatever shines; and it is a yearning to be released.” But this coming-of-age tale in the time of sex, drugs, rock ’n’ roll, and Vietnam seems to yearn for embrace as well as release.

Eugene Lowe, who describes himself as “once a constant rhythmic wanderer … now moored in Tucson,” here chronicles his life from age 12 to 18. It’s a poignantly disturbing, eventful period. It opens with young Lowe nervously wetting himself at his mother’s second wedding, and then being left for days on his own. When his mother and her new husband finally returned, Eugene realized this Air Force staff sergeant was no caring “dad.” From then on, Lowe calls him the “Dive-bomber,” and things will not go well in the household.

Born in 1955, Lowe missed the older boomers’ idealistic early free-love, anti-war, civil-rights idealism; he hit its no-longer-idealistic dark side. As a young teen, he got straight into drugs; eventually into LSD. With his family stationed in Germany, his mother, relishing her own victimhood (the Dive-bomber having proved to be a violent, erratic drunk), provided him benign neglect, and Lowe plunged full bore into rebellion. He grew out his hair, defied the Dive-bomber, disrespected school rules, began hitchhiking around Europe, and engaged in the single-minded pursuit of sex he called love. The last two activities would continue to drive him once he returned to his real father’s “care” in the U.S.

In some ways, this is a study in damage — from both social and domestic fracture. Eugene wasn’t an innocent victim, however; he acknowledges the thrill that both he and his drama-prone mother enjoyed in abuse and resistance. It’s a fascinating read. You only wonder what happened in Lowe’s life in the intervening 47 years.

— Christine Wald-Hopkins