More than 50 years have passed since three teenage girls disappeared in Tucson.

And the story that a young Richard Bruns would tell police back then would take some of the city’s innocence while also putting it in a harsh national spotlight.

Bruns had been friends with Charles H. Schmid, a well-mannered and charismatic 23-year-old who associated with teenagers and turned out to be a killer.

It was Bruns who told authorities that his friend Schmid had shown him where two of the girls, who Schmid had killed, could be found.

Bruns helped police find the bodies of the two sisters and testified against Schmid.

By 1966, Schmid was known as the “Pied Piper of Tucson” and had been tried and convicted for the murders of sisters Gretchen and Wendy Fritz. He was later convicted of murdering Alleen Rowe in 1964.

Schmid pointed the finger back at Bruns, saying he was the killer, an accusation many appeared to believe.

Schmid was interviewed about the murders and his life analyzed, but no one outside of law enforcement asked Bruns his side of the story.

He’s telling it now.

After the trials ended and Schmid was convicted, Bruns wrote what he knew of the sordid tale and then stuffed it in a box.

Years later, two of Bruns’ daughters, Lisa Espich and Leah Bruns, were helping their mother go through boxes of old papers and found their father’s story.

The twin sisters knew that their father was involved in the Charles Schmid case back in the 1960s and that he was the one who went to the police, but they didn’t know the details.

Lisa read it right away. Leah wasn’t quite ready to read it then, but they suggested to their father that he publish the manuscript. He declined, not wanting to dredge it up again.

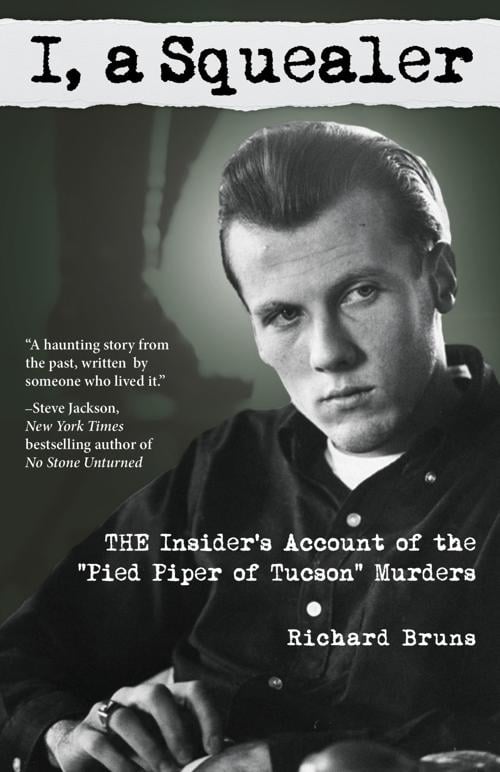

Bruns put it in a closet and thought perhaps he had thrown it away. Years later while helping him move, Leah found the manuscript again and gave it to Lisa for safekeeping. This time they were able to convince Bruns that it was time his story was told. His book, “I, a Squealer,” will be published next month.

The book is an often chilling account of the story of the “Pied Piper of Tucson” from the point of view of an insider.

Life was difficult for Bruns after the trial.

Some apparently believed Schmid’s stories that Bruns was the killer and some called him a rat and finger man. He had trouble getting and keeping a job because of the notoriety surrounding the case.

In a recent interview Bruns gave an example: “I went to a pawn shop to pawn something because I wasn’t working, and the guy said, ‘Are you the Richard Bruns we’ve all been reading about?’ I said, ‘Yeah,’ and he said, ‘I don’t want to do business with you.’”

Bruns said that once he was playing pool with his brother at a bowling alley on South Alvernon Way. “At the table next to us was somebody I recognized had gone to prison; he was a big dude and I thought, ‘Oh my God, I’m in trouble.’ Then he shot a couple balls and said, ‘How you doing, Richard,’ and he was friendly as hell.

“So here was somebody who was in prison and lived by a strict ‘you don’t squeal’ code and he recognized the difference between squealing on somebody for stealing a candy bar and squealing on somebody who was out there killing girls. It was quite a different thing. But your average high school kids who grew up with things and had these wonderful jobs, they’d drive by my house and throw stuff and yell derogatory things, mainly about being a rat.”

Perhaps one reason people didn’t trust Bruns was that he didn’t turn Smitty in immediately when he bragged that he had killed Alleen Rowe. But Bruns said he had no proof.

After he knew about the Fritz girls, Bruns became obsessed with the idea that Smitty would kill Kathy Morath, a girl Bruns had dated. Bruns began stalking her with the idea that Smitty couldn’t kill her while Bruns was watching her.

Kathy’s parents took Bruns to court. He was ordered by a judge to move to Columbus, Ohio, for six months to live with his grandmother.

Within a few days of arriving in Ohio, Bruns called the FBI and turned Smitty in for the murders.

“Once I turned him in, I never went down her street again in my life,” Bruns says of Kathy. He no longer needed to protect her.

Bruns stayed in Tucson with his wife and daughter. The twin daughters followed. After Bruns and his wife divorced, he went to the University of Arizona, graduated cum laude and became a teacher. He was in his 30s by then.

Bruns, now in his 70s, is finally telling his story because he said he is tired of the way books and movies have portrayed him as a loose cannon who could be capable of anything, especially after his stalking of Kathy. He says he doesn’t even recognize himself in these portrayals.

Bruns wrote his story after the trials to keep the details fresh in his mind at the time. He has not read the manuscript since. His daughter, Lisa Espich, was the driving force behind getting the book published. She wants her father’s story told in his words to set the record straight.