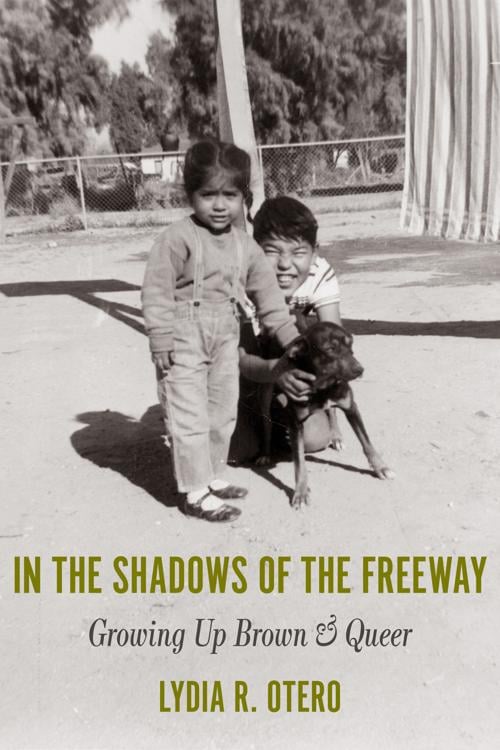

If a reader asks Lydia Otero, author of “In the Shadows of the Freeway: Growing Up Brown & Queer,” whom she wrote the book for, she would say that she wrote it for an audience of one: herself.

“Throughout the book I tried to make it about me and my experiences,” Otero said in a phone interview.

However, in writing for herself, Otero’s book is for people interested in the themes — class, gender and race — that she explores in her memoir of growing up in a Tucson barrio wiped out by “urban progress.” The universal truths in her story, from when she was born in 1955 to 1973 when she graduated from high school, continue to force us to confront the challenges faced by people in communities of color and nonconforming heterosexual norms.

Lydia Otero

“Even before I entered the first grade, my older brother had nicknamed me ‘La Butch.’ My queerness never faded in the background, and it stood at the core of almost every dialogue that took place in my head and every decision I made,” she wrote in her introduction.

She’s genuinely surprised at her book’s positive reception. The book was included in Pima County Public Library’s 2021 Southwest Books of the Year. On March 7, Otero will take part in the Tucson Festival of Books. She’ll appear alongside Nogales-born author and poet Alberto Álvaro Ríos, Arizona’s first state poet laureate, with moderator Mari Herreras. The panelists will talk about place and community, and the dislocation of families and the burial of their stories.

Otero grew up in Barrio Kroger Lane, on Farmington Road, in the southwest quadrant of West Starr Pass Boulevard and Interstate 10. Otero’s early years coincided with the city’s demolition of its Mexican past and neighborhoods inhabited by working-class families, overwhelmingly Mexican-American. While many of her neighbors fled because of the freeway, Otero’s family remained.

Kroger Lane and other barrios were razed or split by the interstate and later by downtown’s urban renewal. Otero, a retired professor of Mexican-American Studies at the University of Arizona, delved deep into the erasure of the old barrio in her book “La Calle: Spatial Conflicts and Urban Renewal in a Southwest City.”

In some ways, “In the Shadows of the Freeway” is a prequel to “La Calle.” She relies on personal memory and archives to tell her unique story of displacement and division caused by a freeway and attitudes of the time about her queerness.

Otero examines her life, her relationship with her mother, Chita, and the lives of her family and neighbors through the lens of loss and exclusion. The city’s power structure, which revved up before World War II and went into overdrive of destruction after the war, viewed the barrios as dispensable and embarrassing. Tucson saw itself more white than brown, more Anglo than Mexican. City and business leaders ignored the barrios at best. At worst, they caused great pains and wounds.

“Conditions in my barrio, such as the lack of parks, streetlights, and proper drainage, were based on decisions made at city hall by administrators and politicians who prioritized the needs of those in more upscale neighborhoods,” Otero wrote.

The environment that the Chicano working-class families lived in was placed in peril. Then there was no name for it. Today we call it “environmental racism.” Another clear historical example is that today many Tucsonans live with the consequences of the 1950s poisoning of drinking water on the south side contaminated by trichloroethylene (TCE), a cancer-causing industrial solvent. Routinely dumped on the ground or into drains, TCE caused numerous health problems for hundreds of Tucsonans.

The effects of environmental racism in Otero’s story were deadly. Her grandfather was mowed down while crossing the flattened roadway before it was elevated. There were no protected pedestrian crossings for the residents west of the freeway. And her older brother, when he was 9 years old, drowned in one of the several gravel pits dug along the Santa Cruz River. Rocks and sand were extracted to satisfy the increasing demand for cement to build the surging white suburbs. The sand pits were unprotected by its owners and the city, and the Otero family was ignored when it sought justice.

“What happened to that neighborhood was important to me. I see brown neighborhoods that are no longer there,” Otero said.

Documenting the violent deaths in her family, writing about the unfairness of how her barrio was treated was not a catharsis. Some writers feel that putting difficult memories to paper relieves them of the chokehold that they have lived with. Otero said the unhappiness remains. That violence, she said, remains with her.

Still she felt compelled to write her story. Unmasking it was intentional, she said. In telling the story, Otero tells the stories of many Tucsonans who were not born in a place that gave them privilege.

“We don’t take into consideration place,” she said. “Privilege is grounded in place.”

While the reader will share in Otero’s pain, there is also a sense of attachment and relief for readers, especially young people who are discovering their sexual identity and facing difficult family responses.

After the book was released in late 2019, Otero gave a presentation at Pueblo High School, where she graduated from. The event was sponsored by IAMME, a student group. A shy trans student who was accompanied by the student’s supportive mother approached Otero.

The mother was beaming, Otero recalled. The mother thanked her for the book. “This means a lot to him,” Otero recalled the mother telling her.

That would have not happened when Otero attended Pueblo. The exchange with the trans student is indicative of good change, she said. Still it is difficult for young people to acknowledge their sexual identity without jeopardizing their family support, Otero added.

It’s also unlikely a book like Otero’s would have been written then. Today, Otero’s book is for the trans student, the mother and all of us.