Jim Lowell is used to the question: “When are you going to turn your home into a museum?”

And it’s not just because the walls are packed with paintings.

It’s also the Victorian automatic musical instruments.

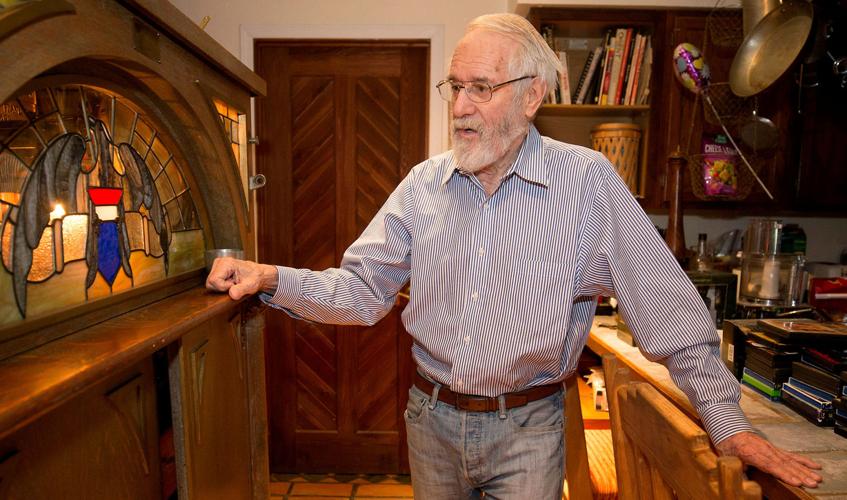

With the exception of the bathroom, there are the instruments in every room of the Lowell house. They range in size from large machines that resemble cabinets to small music boxes that rest on the coffee table.

There are about 40 of the instruments, and some date back as far as the 1830s. Lowell has been building his collection since the late 1950s, when he got a player piano and learned more about restoring instruments.

“Everybody says it starts with a player piano,” he says. “Then along the way you find out about the other things.”

The look and sound of the instruments drew Lowell to collect more of them over time.

He gestures to the carved instruments around his home. They are nice pieces of furniture, he says.

Some of the instruments play large shiny metal discs perforated with small holes and indentations. With the insert of a coin and a few winds of a crank, the disc turns and the magic happens. Music, ranging from beloved classics to unfamiliar tunes, fills the room.

And it fills it frequently: playing them is part of their upkeep.

The choices of music to listen to have expanded with the collection. Lowell’s collection grew as he got more involved with various musical instrument collectors’ organizations and saw their ads for instruments. Some instruments were even shipped from Europe.

“All the (instruments) we have are quite different from each other,” he says.

With many of the instruments came an opportunity to restore them to their original style and sound, a process that sometimes requires Lowell to experts to make some of the parts for the instruments.

Restoration can be a lengthy process. One of Lowell’s additions to his collection, the Wurlitzer BX with an automatic roll changer, has taken six years to restore. The instrument, a large orchestrion with 38 organ pipes and 17 bells, is ornately decorated with intricate carvings in its wooden build and stained glass panels. Topped with a whirling colorful light, the instrument looks far different than it did when Lowell first purchased it.

The Wurlitzer had been in a river boat that got hit by a runaway garbage barge on the Mississippi River in the middle of the 20th century. Dragged out of water that had risen above its keyboard and in need of repair, the instrument passed through the hands of several restorers. It was still in need of restoration when Lowell bought it.

He put in a new soundboard and updated the “wonderlight” — the spinning light on top. The instrument plays 30 different tunes. Lowell says the restoration work is almost completely done.

“I don’t think there’s a piece of dust on that piano that isn’t restored,” says Linda Rickert, who has been engaged to Lowell for 15 years.

Lowell now does much of his newer restoration work with his adult son, who Lowell says is used to being around the instruments.

“He grew up while I was (restoring),” Lowell said. “And that let him learn a lot about it.”

Lowell’s own interest in these instruments sparked when he was growing up in Ohio and his neighbor let him borrow a Regina music box. He now has three Regina-made instruments in his collection.

“I really liked (the music box), but I didn’t have one for many years,” Lowell says.

From Ohio, he went to Columbia University in New York. He started visiting Tucson regularly in the early 1950s. At the time, he was a herpetologist and he was drawn to this area because of its rattlesnakes.Lowell moved to the Old Pueblo in 1959.

“When I was first here, we would just run around the desert collecting critters,” Lowell says.

His affinity for collecting extended to his work in herpetology, where he would keep snakes he had collected in his bathtub to study them.

He later was one of the founders of Pima Community College and worked as a professor of genetics and biology at the college for around 35 years. He now is retired and works on restoring the instruments whenever he wants to.

“Right now the market for this stuff has dropped a little,” Lowell says. “Nobody’s selling them now because the prices aren’t what they should be or have been.”

Though Lowell says he doesn’t know of anyone in Tucson with a collection like his, he has found a community of other instrument collectors around the country. His travels to see others’ collections have taken him to Southern California, Maine and around Arizona.

His collection has drawn a crowd of its own, too. People often come to see it and this March, members from the Southern California chapter of the Music Box Society International are set to visit his home.

Lately, Lowell is setting his sights on the next addition to his collection, possibly an orchestra box. He flips through a copy of “The Golden Age of Automatic Musical Instruments” and points out glossy pictures of different instruments, speaking admiringly about them and collections he has visited.

But until the new one comes in, he still has repairs to make on that Wurlitzer. Lowell may not have plans to open a museum, but his life as a curator never stops.