It’s the grandest gorge on the face of the Earth.

One look into the Grand Canyon — a mile-deep maze of carved-stone majesty slashed into a Northern Arizona plateau — inspires an outburst of superlatives from many visitors:

Unbelievable!

OMG!

Awesome!

My golly what a gully!

This year — as the National Park Service celebrates its centennial — Grand Canyon National Park reigns as one of the crown jewels in the nation’s public-lands treasure chest.

The 277-mile-long natural wonder is revered not only for its incomparable, multi-hued rock formations but also for its cool forests, blooming deserts, frothing waterfalls, abundant wildlife and wealth of geologic and human history.

Those attractions — along with grand lodges such as the historic El Tovar on the canyon’s South Rim — have drawn more than 6 million visitors this year. That’s an all-time record for annual attendance.

Christine Lehnertz, who took over as superintendent of the park in September, has an idea of what lures so many people to the canyon.

“I think the Grand Canyon gives us an opportunity to have a personal experience of awe,” Lehnertz says.

“A part of it is the immensity of the canyon and the perspective it builds in each of us when we have an opportunity to be on the rim, along the water or in between,” she says. “It lets us think about our place in the universe.”

ORIGINS

What created the Grand Canyon?

Short answer: The persistent, very persistent, Colorado River carved the canyon into a high plateau.

How old is the canyon?

Best estimate by park scientists: It’s 5 to 6 million years old. But other experts believe its age is much greater than that.

A brief description of the geologic processes can be found on the park’s website.

“Grand Canyon is the result of a distinct and ordered combination of geologic events,” says the website entry. “The story begins almost 2 billion years ago with the formation of the igneous and metamorphic rocks of the inner gorge. Above these old rocks lie layer upon layer of sedimentary rock, each telling a unique part of the environmental history of the Grand Canyon region.

“Then, between 70 and 30 million years ago, through the action of plate tectonics, the whole region was uplifted, resulting in the high and relatively flat Colorado Plateau. Finally, beginning just 5 to 6 million years ago, the Colorado River began to carve its way downward. Further erosion by tributary streams led to the canyon’s widening. Still today these forces of nature are at work slowly deepening and widening the Grand Canyon.”

HUMAN HISTORY

People have been exploring the Grand Canyon, and living in it, for thousands of years.

According to the National Park Service, the earliest known period of occupation, known as the Paleoindian period, began some 11,500 years ago and lasted about 3,000 years to the end of the last ice age.

A Park Service document called “Prehistory of the Grand Canyon” says that in those long-ago days, “small, mobile bands of people hunted megafauna such as mountain goats, ground sloth and bison; and gathered wild plants. Paleoindian sites are extremely rare in the Southwest. One known site has been found within the Grand Canyon.”

Over the ensuing thousands of years, native peoples relied on hunting and gathering and later cultivated plants. They built storage granaries in canyon cliffs, made baskets and pottery and went on to construct masonry pueblos and subterranean rooms known as kivas. By A.D. 900, puebloan peoples were cultivating maize along the Colorado River corridor.

“It is believed that by A.D. 1300, semi-nomadic, non-puebloan peoples occupied the river corridor of Grand Canyon,” says the Park Service document. “These Pai and Paiute hunter-gatherers had a stable subsistence economy based on combined agriculture and hunting and gathering, supplemented by trade.”

According to historians, the first Europeans to visit were members of Francisco Vasquez de Coronado’s expedition in 1540.

Over the next several centuries, the canyon was hardly seen as a worthy destination.

In 1861, a U.S. Army lieutenant named Joseph Christmas Ives echoed a then-common sentiment about the so-called “God-forsaken” terrain in and around the Grand Canyon.

“This region is, of course, altogether valueless,” Ives wrote. “It can be approached only from the south, and after entering it there is nothing to do but leave.

“Ours has been the first, and will doubtless be the last, party of whites to visit this profitless locality. It seems intended by nature that the Colorado River, along the greater portion of its lonely and majestic way, shall be forever unvisited and undisturbed.”

But later came John Wesley Powell, a one-armed Civil War veteran who led the first documented expedition through the Grand Canyon on the Colorado River in 1869. Powell’s journals awakened the nation to the wild, incomparable beauty of the little-known inner gorge and inspired a passion for the canyon that endures to this day.

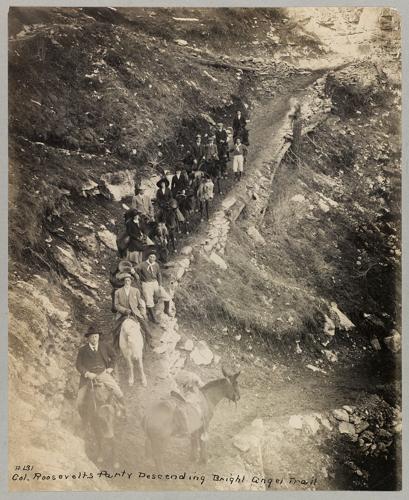

President Theodore Roosevelt established a precursor of today’s park, Grand Canyon National Monument, in 1908. But it wasn’t until 1919, seven years after Arizona became a state, that Congress passed a bill creating the park and President Woodrow Wilson signed it into law.

GRAND ACTIVITIES

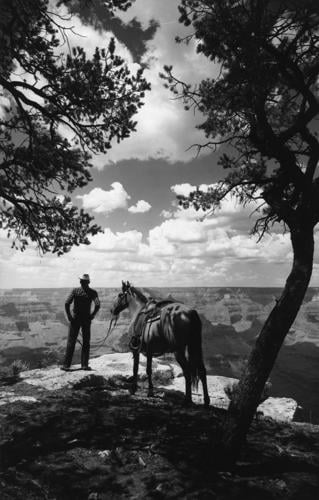

Visitors to the Grand Canyon can experience its splendors in a wide variety of ways — from simply walking to an overlook and snapping selfies while spewing superlatives, or strolling along a flat rim trail, to hiking into the gorge, trekking all the way across it, or rafting the Colorado River through thrashing rapids.

No matter the approach, the canyon does its part by dazzling the daylights out of most visitors with its sheer, rock-solid, timeless beauty.

The canyon’s South Rim — at an elevation of about 7,000 feet, 80 miles northwest of Flagstaff — is open all year and receives most of the park’s visitors.

The North Rim — at an elevation of about 8,000 feet, south of the community of Jacob Lake — is closed from Oct. 15 through May 15 annually.

Each of the rims offers numerous spectacular viewpoints accessible by vehicles and, during part of the year, by canyon shuttles.

Then there’s everything between the rims. Vista-rich trails — including the popular Bright Angel and South Kaibab routes — lead legions of hikers and mule-train travelers to sites at the bottom of the canyon, including historic Phantom Ranch.

Rafting the Colorado River through the canyon is, for many, the adventure of a lifetime.

Not uncommonly, a first awestruck visit leads to a lifelong love affair with the grand abyss.

“I think I was 5 when I first saw the Grand Canyon,” says Helen Ranney, a resident of Flagstaff who now works as a guide in the canyon with The Wildland Trekking Co. and Arizona Raft Adventures.

“I remember being out near the rim and my mom holding on to the back of my shirt.”

Later in life, Ranney was drawn back again and again. She lived in the park for more than three years while working with the Grand Canyon Association, and she now spends much of the year guiding hikers and serving as a volunteer backcountry ranger with the Park Service.

“The Grand Canyon has changed my life,” she says. “It recharges me. It’s almost a church for me. I recharge and find my peace.”

Mike Harris, a member of the Southern Arizona Hiking Club and a former chief guide for the group, has his own trove of rich Grand Canyon experiences.

“I hiked from the North Rim to the South Rim on a day when it was 110 degrees at Phantom Ranch,” Harris recalls. “I’ve seen elk on the South Rim.

“I take a lot of pictures at the canyon,” he says. “I’m awestruck every time I’ve been down there or up on the rim. And I’m going back in April for a three-day backpack trip with my son.”

Like so many others, Harris says he never ceases to be excited about a planned visit.

“People think it’s hard to get excited about a big hole in the ground — until they see it,” he says.

Even those who never venture into the vast expanse of the inner canyon come away from a visit with incomparable memories — of a sunset walk along the South Rim followed by a canyon-side feast in El Tovar’s restaurant, or perhaps an evening of stargazing outside the rustic North Rim lodge.

CANYON CHALLENGES

For all the inspiring beauty, a site that receives 6 million visitors in a single year faces some daunting challenges. Among them:

- Crowding at viewpoints sometimes detracts from a peaceful or contemplative experience.

- Traffic congestion on canyon roads and in parking lots.

- Concerns about runaway development in communities near the canyon and impacts from proposed mining ventures near the gorge.

Lehnertz, the park superintendent, notes that issues also arise among Grand Canyon’s 500 National Park Service employees and some 2,000 or so concessionaires and others.

Since replacing a former superintendent who departed in the wake of revelations of widespread sexual harassment among park employees, Lehnertz says her “No. 1 priority is a creative and respectful workplace here at the Grand Canyon.”

SIGHTS TO SEE

Travel to the Grand Canyon and something is likely to capture your attention practically anywhere you look. Here’s a short list of some of the top observation sites and destinations:

- Mather Point — Peer down from this overlook, east of Grand Canyon Village, and you’ll need approximately a nanosecond to understand why the canyon is considered one of the natural wonders of the world. The point serves up a soaring hawk’s view of the canyon’s splendor — from top to bottom and rim to rim.

- Hermits Rest — The views from this outpost and overlook, at the western end of a road tracing the South Rim, are breathtaking. A stone building designed by architect Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter crowns the site.

- North Rim overlooks — The North Rim provides a different experience from the South Rim because of its higher altitude, more remote location and, some say, more spectacular overlooks. Among them are Bright Angel Point, Cape Royal and Point Sublime.

- El Tovar Hotel — The hotel, perched a stone’s toss from the edge of the South Rim, was built in 1905. It has hosted Theodore Roosevelt, Albert Einstein and a long list of other noteworthy guests. But the building itself — with its wood-frame construction, namesake tower and elegant dining room — outshines its guests.

- On the trail — This is where many of us move beyond mere observation to truly experience the canyon. Here are a few sentences from a personal experience in 1994:

At a place called the Eye of the Needle, I feel the Grand Canyon in the pit of my stomach. The feeling is sheer drop. The feeling is narrow trail. The feeling is don’t fall. The Eye of the Needle, a short passage on the North Kaibab Trail named for a nearby needle-shaped spire, is essentially a ledge that was blasted into a vertical wall of what I dearly hope is solid limestone. The ledge is 5 or 6 feet wide and perfectly safe — so long as you watch where you walk. I watch very carefully indeed.

For more photos of Arizona’s National Parks, go to tucson.com/parks