Felipe Molina realizes there’s a segment of history, particularly that of his culture, that is slowly disappearing with age.

Molina is a Yoeme − more commonly known in Southern Arizona as Yaqui Indian − who is trying to keep the history of his culture alive through education, writings and, in mid-February, a community tour through the various Yaqui communities in the area, some of which still exist and others which are just a vision of the past.

At 65 years old, Molina likes to share what it was like to live in a small house made of mud and sticks, and how happy a family could be with its modest existence in a time when the world around a Yoeme village was headed toward where we are today.

“There’s some people still interested in finding out about the way we lived,” Molina said. “I think it’s important because we carry on our language, we carry on our traditions and our ceremonial lives.”

On Feb. 11, Molina will lead a tour of the Tucson and Marana Yaqui communities in an event organized through the Old Pueblo Archaeology Center, a local non-profit whose mission includes, “to educate children and adults to understand and appreciate archaeology and other cultures.”

The tour is $25 ($20 for Old Pueblo Archaeology Center members). Reservations and prepayment must be made by Feb. 8 to participate in the tour.

“It goes back to our mission to educate people about Arizona and Southwestern archaeology, history and the cultures,” said Allen Dart, executive director of the Old Pueblo Archaeology Center. “Cultures is a big part of that. When most people think of archaeology, they think of the Tohono O’odham being the main culture in the area. But a major component is the Yaqui or Yoeme culture that not too many people know about.”

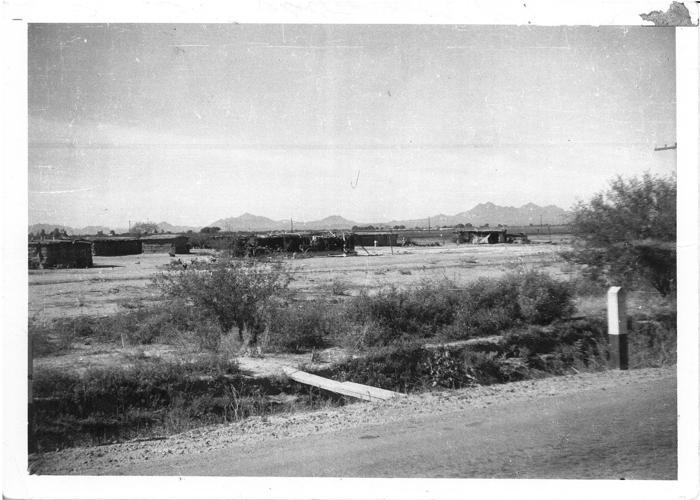

Some of the tour will require some imagination by those who attend because some of the villages on the tour no longer exist, having been displaced over the years as Tucson developed around them.

“Part of the reason for doing this is to get non-native people into the concept that most native cultures, Yaqui and otherwise, tie very high importance to the land and the landscape. Just visiting these landscapes where they originally established communities gives people a perspective of what the land means to native cultures here.”

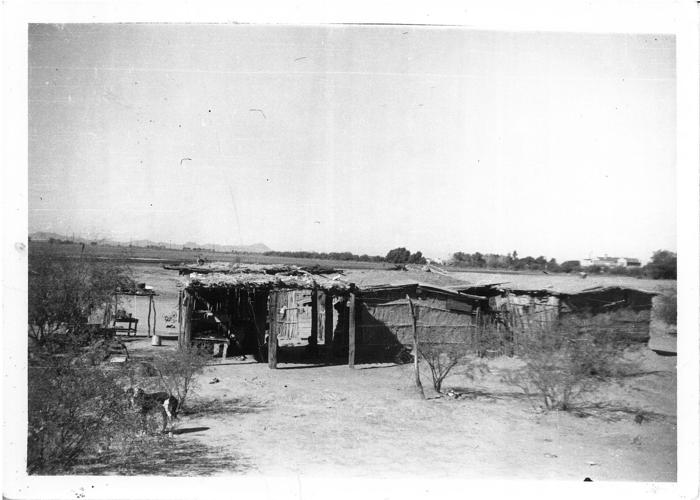

Molina will take the tour to an area near the Santa Cruz River and West Irvington Road where the first Yoeme people migrated from Mexico in the 1890s and early 1900s, living in mud houses known as “jacals” and growing their food.

“That’s the area the elders called ‘Bwe’u Hu’upa’ which means ‘large mesquite,’” Molina said. “We’re going to start there because that’s where the people lived. Some of them had gardens because it was close to the river.”

Because of the time Molina spent absorbing the Yoeme history as a child, he said he will be able to stand where they lived and describe what life was like, who the people were, and what they meant to their community and the history of Tucson as a whole.

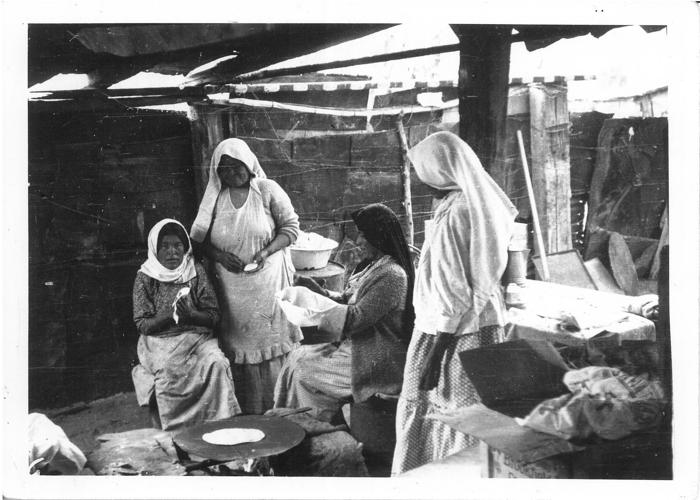

“I will tell them this is where our people used to live,” he said. “They had gardens. They lived in mud houses with ramadas. They collected the mesquite pods which were ground into flour.”

Having lived in one, Molina can describe how a jacal was built, using railroad ties and lumber for framing, saguaro cactus ribs and mud for the walls, and then wood, corrugated metal and mud to insulate the roof.

“That’s what kept it cool in the summer and warm in the wintertime,” Molina said. “You didn’t need much heating.

“I was almost born in one of them. My mother was going to give birth to me but it didn’t happen and I was born at St. Mary’s Hospital. Back then there were midwives in the village. Many people, many of my relatives, were born in that house.”

Molina grew up in the Yoeme village that gave way to Interstate 10 between Tangerine Road and Marana Road. The tour will stop there where Molina can give a first-hand account of living in the farming community and the people who started moving there at the turn of the 20th century.

“Those people worked for the farmers clearing land,” Molina said. “Marana was a big farming area and that’s how they earned money to make a living. My grandfather said that after the Mazocoba Massacre (in 1890 Mexico) many of them came across and some went straight to Marana to look for work and raise a family. My grandfather went there in 1921.”

The villages were small, some with just a few houses and a few families. Others more populated, like the Old Pasqua Yaqui village that still exists east of I-10 and off Grant Road.

“Many families just clustered in small areas,” Molina said.

And they were close.

The jacal was simple but provided a gathering place for families in the villages, Molina said.

“The biggest room was the kitchen,” he said. “It had the stove, the table, the chairs. When you had visitors, that’s where they congregated. And then there would be a bedroom to one side and another to the other side.”

In that day, the kitchen was a place where the young generation was interested in listening to the elders, as Molina did, to understand the culture, the traditions, the ceremonies that seem to be fading with time as the kitchen tables are now surrounded by a younger generation that hardly looks up from their cell phones.

“The job of the elders was to keep the young people on the right path,” Molina said. “If they went sideways they had to tell them a story or give them advice.

“The elders back then lived over 100 (years) because they were living in that area eating the traditional foods and wild greens. I think that’s what they’re trying to pass on to the new generations.”

Molina now finds himself as one of the elders who is doing what he can to pass on his knowledge of the life, the culture and ceremonies to the young generation that gets most of its information, history and knowledge from the technology that surrounds him. And there is hope.

Molina said some impetus for the February tour came from a tour he gave to a group of youngsters last fall.

“I did a little (tour) on my own back in November,” he said. “We visited the first village and I talked to them about the way they carried on their lifestyle, the ceremonial life, respecting the ceremonial kinship that was very important in those days.

“They didn’t know there used to be a village there. They were surprised to hear it. Maybe they drove through there every day or once a week, and they didn’t know there was a community there. They were happy.”

“I will tell them this is where our people used to live. They had gardens. They lived in mud houses with ramadas. They collected the mesquite pods which were ground into flour.” Felipe Molina