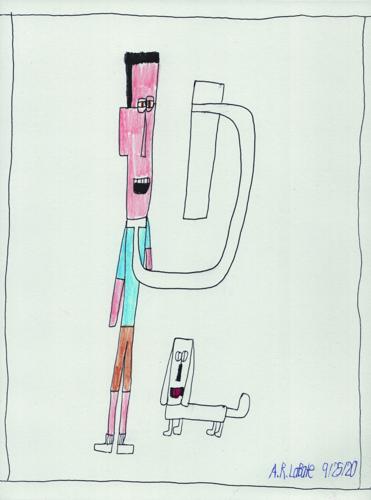

Once considered a haven for people with developmental disabilities, Arizona is denying 4 out of 10 applications for assistance from families that are now forced to fight for services they’ve been promised. Above, 11-year-old Kyra Wade, who is deaf and has autism.

Kyra Wade’s favorite color is pink. The 11-year-old likes road trips and the movie “Monsters, Inc.” She loves to watch people laugh. Her culinary preferences run to noodles and rice.

Beyond that, her parents don’t know much about her needs and wants.

Kyra is autistic and profoundly deaf. She was born premature at about 27 weeks, just a little over 2 pounds, which has impacted pretty much everything: eyesight, hearing, digestion, sleep patterns. A strong tremor in her hand makes it impossible for her to use American Sign Language. Her parents think she recognizes a couple dozen signs.

They know she’s frustrated. Kyra often smacks herself on the side of the head with her hand or bites her palm so hard she draws blood, said her mother, Ka Wade. The Wades assume she is doing it when she is in pain. Kyra is not potty trained, but she got her period recently. Ka couldn’t explain what was happening.

The Wades moved to Arizona in the summer of 2017 with the expectation that services provided by the state would help them care for Kyra. Arizona had long enjoyed a reputation as one of the best places in the country for people with developmental disabilities and their families. Thanks to a special Medicaid program created in 1988, Arizona had an innovative and generously funded system in place.

Arizona’s Division of Developmental Disabilities, or DDD, aimed to keep people with developmental disabilities at home with family, or in small group settings, rather than place them into institutions.

For many years, it worked. The division sent nurses, speech therapists and respite workers to assist families with the responsibilities of caring 24/7 for relatives with autism, cerebral palsy, epilepsy and intellectual disabilities. Care providers were well paid. There were no long waiting lists for help, as there were in other states.

But like many families in Arizona, the Wades discovered that the state’s vaunted system does not always deliver on its promises after years of budget cuts, poor management and leadership turnover. Fewer than a third of the estimated 157,000 Arizonans with developmental disabilities receive any home and community-based services, and an even smaller number actually get access to therapies, day treatment programs, job training, housing and health care — elements designed to allow a person to live as independently as possible.