It’s not quite the “duck and cover” exercises of the 1950s when schoolchildren were practicing to be prepared for nuclear attack.

But state officials want all Arizonans to drop to the ground and get under a desk at 10:18 a.m. Thursday, Oct. 18, as a different sort of drill.

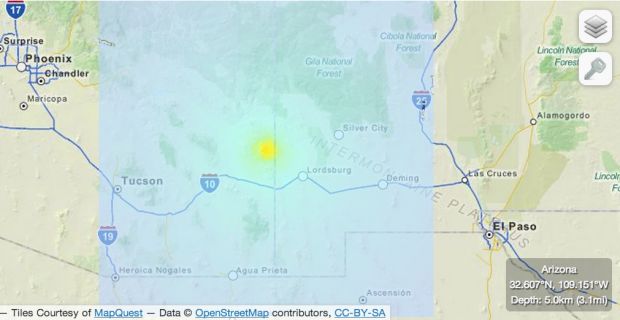

In this case, the issue is earthquakes. And if you think you’re safe here in the Grand Canyon State, history and geology would prove you wrong, says Michael Conway, senior research scientist at the Arizona Geological Survey.

“It turns out Arizona is earthquake country,” he said, albeit not quite like our neighbors to the west. There are about 100 earthquakes a year within Arizona’s borders.

“Most of those go unfelt,” Conway said. “But the potential for magnitude-6 and 7 earthquakes is real.”

One of the highest-risk areas is Yuma, 50 miles from the Imperial fault, which is a splay off the well-known San Andreas fault.

“And that’s a fault system that’s capable of rupturing with a magnitude-7.2 to 7.3,” Conway said. The last rupture on that Imperial fault was 1979, with one prior to that in 1940.

“Yuma got shook pretty good in both of those,” he said.

In Northern Arizona, there are several small faults. But Conway said the Lake Mary fault, which runs under Flagstaff, is capable of delivering “a magnitude-7 event.”

A century ago, there were three magnitude-6 quakes within a six-year period within 25 miles of Flagstaff, he said.

“So it’s been a while since they’ve been rocked,” Conway said. “But these faults remain active faults and they’re going to rupture again at some point.”

And Southern Arizona residents should not get too smug about their safety.

“Just south of Tucson, along the Santa Rita front range, there’s an active fault that can deliver a magnitude-6.5 to 7.0,” he said.

“It hasn’t ruptured in 15,000 or 20,000 years,” Conway said. “But it’s an active fault and the stresses are building and, at some point, probably will rupture.”

Outside the state’s border, a magnitude-7.6 event struck just south of Douglas in 1887. That not only shook up much of Cochise County but also flooded the mines in Tombstone, changing that community’s fortunes.That 1887 Sonora quake also dislodged massive boulders in Sabino Canyon northeast of Tucson.

All of which leads to teaching Arizonans to do the “drop, cover and hold.” That’s so they’ll know what to do, if not for a major quake here, then for when they’re visiting California or somewhere else where it’s not unusual for the ground to shake.

The plan, being coordinated with the state Department of Emergency and Military Affairs, is for an “earthquake-preparedness drill” at 10:18 a.m. Thursday.

The three-step process is simple:

- Drop to the ground.

- Take cover under a sturdy desk or table and protect your head and neck.

- Hold on until the shaking stops.

All that, said Conway, should make a quake in Arizona quite survivable without injury.

“Most of the buildings in Arizona, especially if they’re newer buildings, are not going to collapse,” he said. “So you don’t have to worry about them ‘pancaking’ on you.”

The real problem, he said, is “all the stuff on the ceiling, all the books on the shelves, the glasses, everything else coming off and coming down and hitting on the floor.”

And in some ways, technology has only made things a bit more dangerous.

“In a recent earthquake in California, the greatest number of injuries — there weren’t many, but there were some — involved the flat-screen TVs,” he said.

“They’re unstable as can be,” Conway said. “People try and catch them or people are hiding under them.”

At least part of the reason for the drill, he said, is to make “drop, cover and hold” instinctive.

In the Midwest, Conway said, people get at least a bit of warning about approaching tornadoes. That allows them to find the safest place in the house.

But earthquakes strike without warning.

“In this particular case, we’d rather people didn’t run around their homes looking for a safe place,” he said. “Ideally, there’s a bed or a table or something you can get underneath.”

And there’s something else, especially if it’s a magnitude-5 or higher event: major aftershocks.

“Those major aftershocks, especially in buildings that have been damaged, can be very, very damaging, can even destroy buildings,” he said. “So you’ve got to be ready for those aftershocks that will come within minutes or shortly thereafter, especially the big ones.”