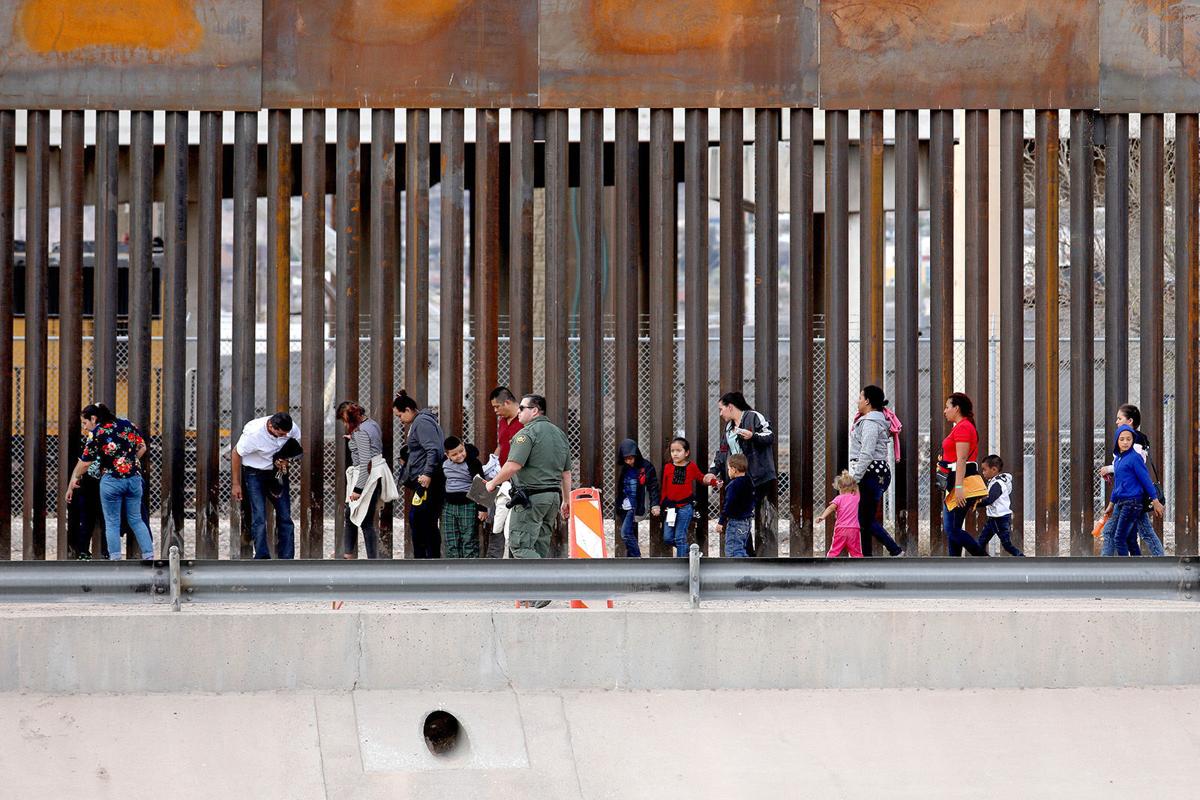

Top photo credit: Gary Coronado / Los Angeles Times ─ Migrants seeking asylum turned themselves in to Border Patrol agents in late March on the El Paso side of the Rio Grande bordering Ciudad Juarez, Mexico.

LEER EN ESPAÑOL: Paradoja en la frontera: La aplicación de la ley podría estar atrayendo a más migrantes

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

The Trump administration has tried prosecuting everyone who crosses the southern border illegally, separating families as parents go through criminal courts and children are sent to shelters. The president has threatened to shut down the border, ordered that asylum-seekers wait in Mexico as their cases are processed, and continues to demand construction of a border wall.

But the migrants keep coming, often in groups of 100 or more, waving down border agents to surrender in hopes they can stay. From Dec. 21 through April 8, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) released nearly 24,000 parents and children, most from Central America, out of 133,500 people arrested at the border.

“It’s a colossal surge and it’s overwhelming our immigration system, and we can’t let that happen,” Trump said during his April 5 trip to Calexico, California.

“The system is full,” he said. “Can’t take you anymore. Whether it’s asylum, whether it’s anything you want, it’s illegal immigration. We can’t take you anymore. We can’t take you. ... So turn around. That’s the way it is.”

But in order to address what Trump calls a national emergency, experts on both sides of the border say policymakers must understand the complex root causes of the migration and of who is arriving.

MORE: Passports to the American dream: Mounting debt, few opportunities keep Guatemalans coming

“It’s not just the conditions in Central America that are propelling people to leave,” said Elizabeth Oglesby, an associate professor of Latin American Studies at the University of Arizona. “It’s the border enforcement itself that acts to produce migration in particular ways.”

Border Patrol agents take two men into custody as they search for several undocumented migrants near the intersection of East Ajo Way and East Benson Highway. Agents took at least four people into custody in last Tuesday’s operation.

Releases on the rise

Every day, ICE officials in Arizona release about 300 parents and children, said Henry Lucero, field office director for the state. About 90 percent are from Guatemala. That doesn’t include migrants the Border Patrol has started releasing in certain areas, including Yuma, but the agency refuses to provide that number.

Daily releases are up from 100 a year ago, he said.

“Most are saying that they are told if they come with a child or children ... that they will likely spend only a few days in Border Patrol and ICE custody and be released to go to their final destination,” he said. And friends or relatives who go through the process confirm it.

During the past six months, Lucero said, parents have started to bring more than one child.

“We think the problem is going to get worse — the word is out in Central America,” said Lucero, and it will continue as long as our laws and policies are unchanged.

A deputy mayor in Yalambojoch, in the western highlands of Guatemala where many migrants come from, talks of the kind of misinformation the administration is up against.

“I don’t know how it is, that law that Donald Trump has over there in the United States,” José Pérez said. “When you enter with minors, you enter transparently, before the eyes of the law, and they get in very easily.”

Pérez doesn’t have any children between 10 and 12 — the age people in the village believe a child must be to be allowed in, so he is not able to come.

When men leave to find work in the United States, their tasks at home, like carrying wood, are left to wives and children, like these in Bulej, Guatemala.

Families in Yalambojoch started to hear last year from men in neighboring towns that kids could be their tickets to a new life in the United States, Pérez said. Now nearly everyone is leaving, planning to send money home so family members left behind can buy food and build the coveted concrete houses that are the primary status symbol here.

“Sometimes the dad leaves with a kid, then the mom leaves with the other and they abandon their home,” said Perez, 44.

Some of the departments (Guatemalan states) with the highest poverty or malnutrition rates are also those where a lot of migrants are coming from.

Pérez has made the trip himself. He came through Arizona illegally, first in 2000, to work in the poultry plants of South Carolina, but eventually was deported and says it became too difficult to try again.

Traveling with children, he said, “is the last option we have to migrate.”

The role of smugglers

Behind this trend is a network of smugglers that includes a person to entice families in Guatemala; someone to transport them to Mexico; someone else to buy food, pay bribes and bus families directly to the U.S.-Mexico line.

One Guatemalan smuggler said family migration from the Central American country picked up in 2013 after parents with children started to cross through the desert, only to be released after they were caught.

“They started to talk among friends and families that there was an opportunity. Today they only grab a child and they are leaving,” he said.

For families, the trip to Mexico costs about $1,300, he said. Then there’s another $800 to $1,000 in extortion money paid to a cartel for the right to cross its territory. That’s about half as much of what it would cost for a single adult who wants to evade authorities and be delivered to friends or family in the interior of the country.

Governments try to vilify coyotes, he said, but they provide a service people want.

“People seek me out,” the smuggler said. “They call and ask if I can do them the favor.”

Reasons for release

What smugglers tell prospective border crossers is not entirely false. Migrants are very likely to be released — but that doesn’t mean they will get to live and work here legally.

“They are being released because of the volume. There are so many families coming over that it’s overwhelming the system, and ICE does not have the detention capacity for them all,” said Lucero, the field office director.

“We kind of go through the process of making sure they don’t have U.S. criminal history, that they are not a threat to their child, and that they have an address where we can mail them their court documents to attend a court hearing in the future.”

ICE has about 3,000 beds for parents and children in three centers: two in Texas and one in Pennsylvania. But one of those is being temporarily converted to house female adult detainees as well.

About 98% of family units sent to a detention center are released before their immigration cases are settled. It doesn’t make fiscal sense, Lucero said, to expand ICE’s family detention under existing laws and requirements.

“Even if we detain a family unit, they don’t go through the entire process because they can only be there 20 days and generally a hearing is not scheduled during that time,” he said.

The 1997 Flores Settlement Agreement calls for immigrant children in custody to be released to a parent, legal guardian or close adult relative. If that is not possible, they are to be placed in the least-restrictive setting appropriate to their age and needs.

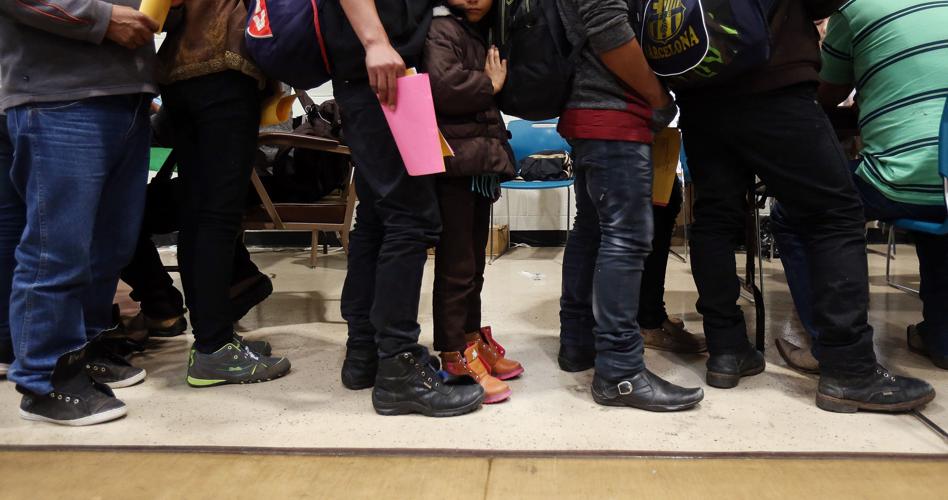

Migrants line up for help with phone calls and travel assistance as Tucson volunteers help hundreds of others with the basics of food, clothing, medical assistance and temporary shelter at a Tucson church. These migrants were among those that Customs and Border Protection dropped off after finding several large groups in the desert west of Tucson last October.

In 2014, when then-President Barack Obama expanded family detention in an attempt to stop the first surge of family migration, advocates challenged him.

Ultimately, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the settlement covered not just minors traveling alone, but also those who came with their parents. It set a general standard that the government couldn’t hold families for more than 20 days.

Of those processed in Arizona, only 5 percent say they fear persecution if returned to their home country, and that holds true for the roughly 12 hours when they are in ICE custody, Lucero said, based on a form Border Patrol agents fill out and explain to the migrants in Spanish.

Most indicate they want to see an immigration judge, he said, which means they could be deported within the 20 days once their identification is verified and travel documents secured.

But expanding detention centers could shift those numbers, Lucero said. Families there talk with other migrants and attorneys, and then claim asylum — starting a process that takes much longer than the time judges have ruled children can remain in custody.

In 2014, when Obama opened a temporary family detention center in Artesia, New Mexico, nearly all of the women arrived there in expedited removal status, meaning they didn’t have the right to see an immigration judge unless they said they were afraid to return to their home country and they passed an asylum officer’s interview.

After spending time at the center, about two-thirds of the women asked to go through the asylum process, attorneys said back then.

Trump and members of his administration call the asylum system a “fraud,” and one full of loopholes. Immigration judges deny 85 percent of asylum claims, Lucero said, “So most people who claim asylum never get it anyway.”

But Lucero’s figures may not tell the entire story. Many of those arriving from Guatemala are indigenous-language speakers who have to communicate with officials in Spanish as they decide which box to check when they are apprehended.

By the time they get to a detention center, they might have had more time and resources to understand the process. Attorneys and immigrant advocates also argue that the low approval rate for asylum-seekers is not so much a reflection of frivolous claims, but of the complexity of the law and migrants’ lack of legal representation.

María García Domingo, 33, leaves home to go to work in the coffee harvest, while her 5 daughters and one son have breakfast

Seeking dignity

Many Guatemalan migrants also leave their country because they decide they can’t afford to stay.

“If you don’t have access to health care, employment, education, if the conditions to live a dignified life aren’t there — it is not an option,” said Julia González Deras, executive coordinator of Menamig, a Guatemalan nonprofit that works on issues of migration and human rights.

Oftentimes there is no single reason why someone leaves.

On top of the entrenched poverty, communities are being displaced by mining and hydroelectric megaprojects, and individuals are victims of violence perpetrated by domestic partners, gangs, organized crime and the state, she said.

This is a population historically disenfranchised in one of the most unequal countries in the world. Discrimination often drives indigenous Guatemalans to leave, said Ruth Piedrasanta, a researcher with Guatemala’s Rafael Landívar University.

“They know that (in the United States) they will be able to achieve things they will never accomplish here,” she said.

While it’s important to defend asylum, the UA’s Oglesby said, “It doesn’t encapsulate everything that Central Americans are to the U.S.”

Central Americans have migrated to the U.S. in large numbers before, she said. Up to 1 million arrived in the U.S. in the early 1980s, including about 200,000 Guatemalans, according to some estimates.

“They aren’t just victims, they are workers and they are members of communities, so at some point U.S. immigration policy is going to have to come to grips with that,” Oglesby said. “We are going to have to have comprehensive immigration reform that recognizes people are here and have a full presence in our society.”

At a time when Trump has said the country is full, Oglesby said that if Mexican migration is any indication, the current crisis won’t last forever. Migration from Mexico dipped after peaking in 2000, she said, as a result of lower labor demand in the U.S., as well as lower birthrates and rising wages in Mexico.

“Let families be reunified. Let workers in that are actually filling a U.S. labor demand,” she said, and support efforts in the home countries.

Young girls learning crops diversification during a workshop, in Yalambojoch, Guatemala.

“Killing a generation”

In Yalambojoch, Per Andersen works to help those who stay. He arrived in the community in 1997 after refugees started to return from Mexico. They had emptied entire villages during Guatemala’s internal armed conflict that left more than 200,000 dead and displaced a fourth of its population during the 1980s.

The community center he oversees, supported by the Swedish government, focuses on education and the environment.

Per Andersen runs a community center in Yalambojoch that helps those who stay.

But lately, the pull to the U.S. has become so strong that officials had to close the only middle school after enrollment dropped by 60%.

“For some, at the age of 13, 14, the only thing they have in mind is to go to the United States. They don’t want to study anymore,” he said. “There are others who do, but then their parents force them to head north.”

Andersen estimates that about 100 people, mostly parents with minors, have left Yalambojoch so far this year. Before long, he said, 80% to 90% of families left behind will depend on remittances, the money sent home from relatives working in the United States.

The center’s goal is not to stop people from migrating, but to prepare the youth for change for when there are no more remittances, he said.

Trump has vowed to cut aid to Central American countries, saying their governments are not doing enough to stop migration.

“I think there’s something that perhaps in the U.S. they aren’t truly taking into account,” said Piedrasanta, the Guatemalan researcher. “We are countries in crisis. While current economic conditions in the country remain, of course this level of migration will continue.”

“We need to create opportunities here at home so people don’t have the need to migrate,” said Paul Briere, a Guatemalan congressman.

“You won’t be able to cut migration 100 percent,” he said. But if instead of 150,000 Guatemalans leaving every year, you have 50,000, that would be a good thing.

“People’s fear of hunger is greater than Trump’s wall,” he said. “They will keep looking for ways to go across. That’s not the answer.”

But fixing the structural issues, and the corruption that diverts resources from communities, will take time, he said. There is no quick fix.

Over the last several months, the Arizona Daily Star has made repeated requests to speak with the Guatemalan consul in Tucson. They have gone unanswered.

“There are some very critical things going on in Guatemala right now and I’m afraid the Trump administration is so fixated on the wall, which is a debacle, and the national emergency that doesn’t exist,” said the UA’s Oglesby. “It is actually not paying attention to the very important things going on in Central America that could actually have a long-term impact.”

Guatemala’s anti-corruption program is in limbo and the country is in what Oglesby describes as a power grab that threatens many of the advances it has made since the peace process.

Meanwhile, Guatemala is losing its youth, “those who should be shaping and educating this country,” said González Deras, the human-rights executive. “The few who are left are excluded (from society) and those who come back will return to be even more so as they face mounting debts. What’s happening is that this country is killing an entire generation.”