Estimates of the number of valley fever cases recorded by local, state and federal agencies vary so widely that they call into question the accuracy of the figures released to the public, a Center for Health Journalism Collaborative investigation has found.

The finding comes during a critical year for valley fever, or coccidioidomycosis. In Kern County, California, public-health officials declared an epidemic in October, predicting more than 2,000 cases in that county alone by year’s end. But data collection methods in California are inconsistent.

In Arizona, the other state with a high concentration of valley fever cases, changes in lab testing for the disease have made it hard to understand the underlying trends.

And Texas, where valley fever is also relatively common, does not publicly report any valley fever cases.

Without an accurate count and without mandatory reporting of the disease, it is difficult for public-health officials, clinicians and businesses that rely on workers in high-exposure areas to plan and staff appropriately. And, the human cost is even higher as the poor tracking contributes to the lack of policy attention to the disease.

“Valley fever is almost certainly underreported, due to physicians and the public not being familiar with the disease,” said Dr. Susan Hoover, an infectious-disease specialist in Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

Hoover and others would like to see states required to publicly report the disease to the federal government, regardless of how many cases they see.

“Diseases are reported according to the state where the patient lives, so having it reportable in the non-endemic area increases awareness among travelers and seasonal residents,” she said. “We would have a more complete picture if it were reportable in all 50 states.”

South Dakota this year made valley fever a reportable disease and is capturing data from people who spend time in Arizona or other places where the disease is endemic. To date, four cases have been reported in South Dakota, all a result of patients exposed in Arizona.

“The mandatory piece of reporting is very important and at least that way we know what is being tested for,” said Dr. Janis Blair, a valley fever expert at the Mayo Clinic in Arizona. “It doesn’t tell us everything, but at least it we would have some sense of how many people out there are walking around with a known diagnosis of valley fever.”

Federal counts

lag behind

At the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), one official said the numbers his agency releases weekly are generally lower than the actual number of cases reported, and blamed the difference on backlogs in the data-entry process at the state and federal levels.

“Those are really released just as provisional, and honestly it takes several months past the end of the year for a state to finalize those numbers,” said Orion McCotter, a CDC epidemiologist.

This means that the nation’s lead agency tasked with protecting the public from serious diseases does not know the full extent of a valley fever outbreak until months after it occurred. Early detection and treatment is especially important as valley fever can spread from the lungs to other parts of the body and ultimately become fatal.

CDC officials would not address deficiencies in the reporting process, and instead referred reporters’ questions to the California Department of Public Health.

“This is just the system that we have right now, and I think lag-time questions need to go to the local and state (agencies) for what their process is, but I think this is the best system available,” Brittany Behm, a CDC spokeswoman, said before abruptly ending an interview.

The data deficiency exacerbates what researchers already describe as widespread underreporting. Experts estimate that valley fever infects more than 150,000 people across the Southwest alone, with 50,000 being sick enough to require medical attention. And yet CDC reports of people infected with the disease have never exceeded 23,000 cases nationwide.

This has allowed valley fever to languish in the shadows as other diseases draw more policy attention and funding. Cocci kills more people annually than hantavirus, whooping cough and salmonella poisoning combined, and yet is not nearly as well known or understood as those diseases.

Local agencies lack reporting guidelines

The responsibility for identifying and warning the public of epidemics falls on local public-health agencies, some of which have no set guidelines for defining epidemics, The Center for Health Journalism Collaborative has found.

For example, one valley fever researcher at the University of California-Davis said he saw a spike in cases in Yolo County, California, but public-health officials there said they only recorded two confirmed cases in September.

Such discrepancies aren’t uncommon. County public-health departments often don’t post up-to-date case numbers, despite having the most accurate data available. This can lead to stark differences among reports from county agencies, the CDC and the California Department of Public Health. For example, the CDPH confirmed 1,204 cases statewide through June. It reported that Kern County logged 455 cases at that time. Kern County itself, however, reported 890 cases to The Bakersfield Californian.

There’s another problem. Because the cocci fungus never leaves the body after infection, it’s not immediately clear whether all 890 cases are new for 2016, or if some are old cases of valley fever that were detected in testing patients for other diseases.

Some high-ranking county health officials weren’t aware of the disparities between local, state and federal data.

“I’m definitely going to look into it because it’s important that we’re on the same page,” said Gilda Zarate-Gonzalez, deputy director of the public-health department in Madera County, California.

The differences in case numbers and the lag time in reporting are so pervasive at all levels that Kirt Emery, an epidemiologist at the Kern County Department of Public Health Services, said it’s the first thing he’d change to get an accurate picture.

“If I were a millionaire and could divvy up my money, my first goal is to get the tests in and move resources so they could get it in their computers, or get it back to the doctors to manage the patient within 24 hours,” Emery said.

Arizona lab changes cause confusion

The delays in reporting the disease begin with the time lag between a person being exposed to the fungus and actually getting sick. It can take as short as one week but as long as four weeks for the fungus to incubate and actually cause symptoms. Then there may be an additional delay between a person noticing symptoms and going to see a health-care provider.

The Arizona Department of Health Services conducted a study that found the median time between symptom onset and diagnosis in Arizona was 55 days.

Once the disease is diagnosed, Arizona is generally faster than California in reporting the disease trends publicly. The trouble is the way laboratories test for the disease.

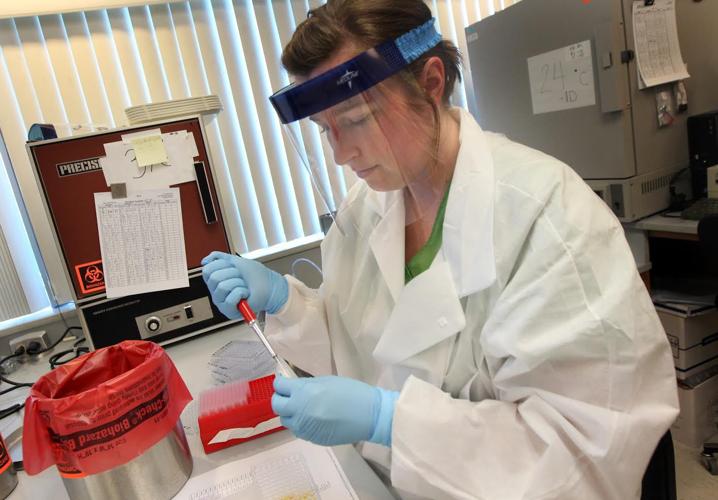

The disease is often detected in a lab test from a saliva or blood sample, and that initial diagnosis can be confirmed or negated by subsequent tests. In 2009, the laboratory that processed most of the valley fever tests in the state began including the initial test in the total count of valley fever cases regardless of whether a follow-up test was positive or negative. The number of reported cases immediately doubled. So by 2011, Arizona had its highest reported valley fever rate in two decades: 255.8 cases per 100,000 residents.

State officials acknowledged to the Center for Health Journalism Collaborative that the lab reporting change may have resulted in false positives being included in the counts, but they have not examined the numbers to determine how many. They also noted that while there are false positives in the first test, there also are false negatives with the second test. So the change in lab reporting allowed the state to include patients who did have valley fever but were given a false negative test.

“Add in possible fluctuations in the actual occurrence of disease and trends become difficult to interpret,” Arizona health department spokesman Benjamin Palmer wrote in an email.

In late 2012, that same Arizona lab changed manufacturers for the tests that it uses, which state officials say may have resulted in a decline in false positives. Together, those changes make it difficult to track the disease.

Last year, a spike in reported cases prompted an investigation by the Arizona Department of Health Services. It did not determine what caused the rise in cases. But weather patterns that affect the growth, spore formation and dispersal of the fungus that causes valley fever are likely a factor, department epidemiologist Shane Brady said. An increased recognition by health-care providers, added awareness among the public and increases in the number of people with weakened immune systems could also influence the reported caseload, he said.

By the end of 2015, the total reported valley fever caseload in Arizona was 7,622, including 50 deaths. Through Nov. 1 of this year, the reported cases have totaled 4,971. Data on deaths so far this year is not available.

“Epidemic” is ill-defined

With case numbers high in Arizona, why didn’t the state declare an epidemic?

Brady blamed the uncertainty about the valley fever trend line. An epidemic is generally defined as unusually higher than the baseline of what’s considered normal, but in Arizona the surveillance changes have made that baseline difficult to define.

“We usually say we have a high number of cases versus an epidemic,” Brady said. “We’d have to have consistent reporting for multiple years to have a baseline.”

Some California counties that have seen large spikes in reported cases have not declared epidemics, either. There are no uniform guidelines across the state for when county health agencies should declare an epidemic.

Public-health officials also expressed reservations about using the word “epidemic” for fear of scaring the public and portraying an image of endemic regions as less inhabitable.