Tucson once had an Indian School and a street named after it — but both are gone.

On August 24, 1886, T.C. Kirkwood, superintendent of the Board of Home Missions of the Presbyterian Church, petitioned the Tucson Common Council for a grant or extended lease on 15 acres of land just west of the university to build an industrial school for Native American boys. The council let a 99-year lease at $1 per year for an area of four blocks near the university. The Board of Home Missions then purchased 42 acres on the Santa Cruz River from Sam Hughes for its farms.

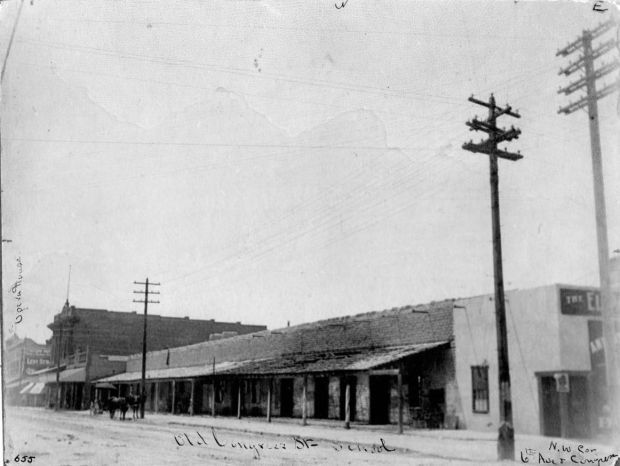

While the school was being built in early 1888, Mary Whitaker used a temporary site — the old adobe public school building on Congress Street — to teach about 10 pupils. Later that year, the school’s first permanent superintendent, Rev. Howard Billman, arrived and the school opened with 54 boys and girls.

|

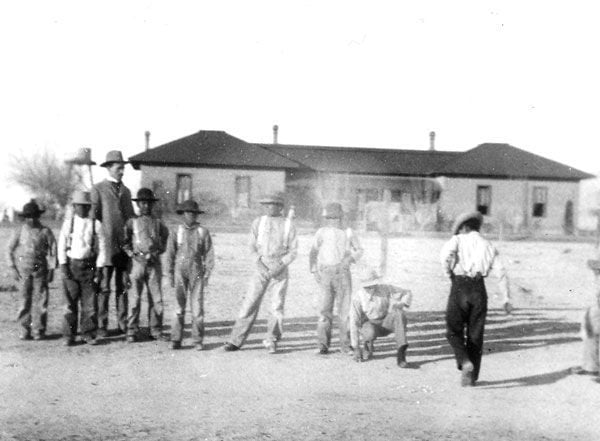

The new boarding school was semireligious. Boys learned trades such as farming, blacksmithing, carpentry and tinning, while girls were taught sewing and similar skills.

In 1890, additional buildings were finished. The stone and adobe work was done by Jules Flin, whose daughter Monica later founded El Charro Restaurant. Even with the additional space, the school soon became inadequate for the demand and students had to be turned away. The following year, Fort Lowell was abandoned and transferred to the U.S. Department of the Interior for use as an Indian school, but it appears it was never used for this purpose.

In 1894, the Tucson Indian School became the last of the schools run by the Presbyterian Church to stop accepting government aid. The same year, boys from the school helped build a small bridge and built chairs for a new Native American church, while the girls sang in a cantata, a religious-themed musical work, at an opera house in town.

By 1895, Rev. Billman had become the second president of the University of Arizona and the Rev. Frazier Herndon became superintendent of the Tucson Indian School. Herndon, who came from Missouri, soon wed one of the teachers, Elise Prugh. Under his direction, the school entered into a contract with the city of Tucson to grade and maintain streets as a way to raise funds. He also expanded the curriculum and brought in more students. One student, Jose Xavier Pablo, who may have been the first Tohono O’odham to graduate from the school in 1903, later became a leader in the tribe.

|

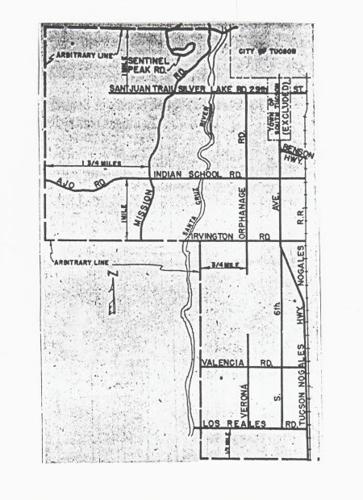

Around 1903, Rev. Herndon set up the Papago Mission (sometimes listed as an Indian school) around what is now 22nd Street and 10th Avenue. From there, he and his wife carried out missionary work with the Tohono O’odham. In 1904, when George Pusch recorded a subdivision called the Native American Addition just north of that location, he recorded four street names: Papago Street, Sacaton Avenue, Quijotoa Avenue and Herndon Place. The latter was named in honor of the Herndons and still exists. The other three seem to have disappeared in the 1950s.

The school next was under the direction of Rev. Haddington Brown, who along with the Presbyterian Board of Missions on Dec. 31, 1906, purchased the land near the university from the city for $480 and resold it to a developer for a sizeable profit. Then, in 1907, the Board of Missions bought 160 acres just east of the Santa Cruz River and about 4 miles south of downtown for a new school.

On March 25, 1907, the Escuela Post Office was set up on campus, with Rev. Brown as postmaster. The name was chosen after the U.S. Post Office rejected the name Indian School Post Office. Many people came to know the Tucson Indian School as Escuela. The new school opened in the fall of 1908.

In 1912, Pima County made the dirt path in front of the new school a county road, but it doesn’t appear the road was given a name.

The school went through several superintendents until 1915, when Martin L. Girton took the helm for 26 years. By 1920, it appears that the name Indian School Road was in use.

|

In a pamphlet written by Girton in the mid-1930s said, “The school was originally organized for two tribes: the Pimas and Papagos (Tohono O’odham), but at present the Maricopas and Apaches are also represented....Girls are graded on their ability to darn a stocking just the same as on their ability to ‘do sums’ (and) boys on their ability to handle a hoe as to recite history.” He also wrote that, the “School plant covers 160 acres, 60 acres under irrigation, has 9 buildings, capacity 130 pupils.”

In 1940, about 18 tribes were represented on campus. Around 1950, Indian School Road was made part of Ajo Way.

In 1960, the Tucson Indian Training School at 802 W. Ajo Way — then under its final superintendent, William D. Hennessy — closed its doors. Four years later the Tucson Citizen newspaper announced that the landmark was being razed to make room for a shopping center.