Arizona's Verde Mining District has historically been one of the richest outcroppings of copper ore in the world, with the United Verde and United Verde Extension Mines producing over $4 billion in recovered metals.

Electrification of the United States in the late 19th century, followed by World War One, increased demand for copper extraction.

Jerome went from an unincorporated camp of 500 residents in 1892 to a population close to 10,000 in 1916. By 1900, it overtook the Copper Queen Mine as the most productive copper mine in the Arizona territory, yielding 40 million pounds of copper per year.

The massive sulfide deposits of Jerome include pyrite, chalcopyrite and sphalerite in quartz matrix, along with carbonate minerals modified by the supergene process involving descending meteoric waters from the Earth’s surface mixed with the chemical processes and mineral reactions of weathering.

By 1894, the Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railroad connected Ash Fork to Prescott. William Clark built a 27-mile narrow gauge line that enabled Jerome to connect to it through the hills at Jerome Junction. Frequently referred to as the “crookedest line in the world,” it twisted by 186 curves, some at 45-degree angles.

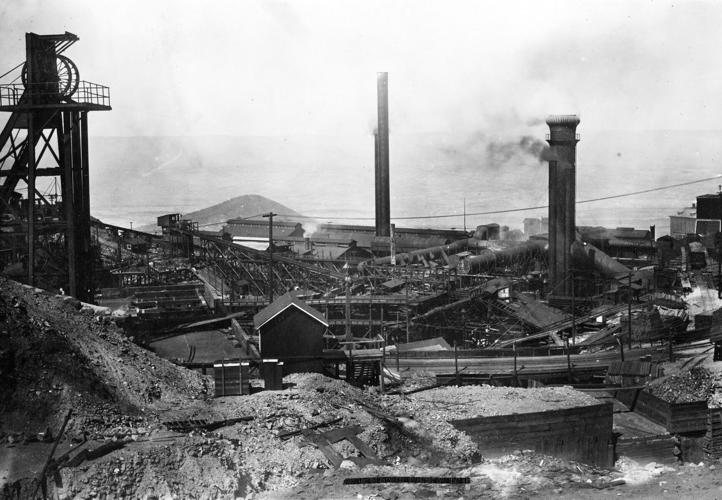

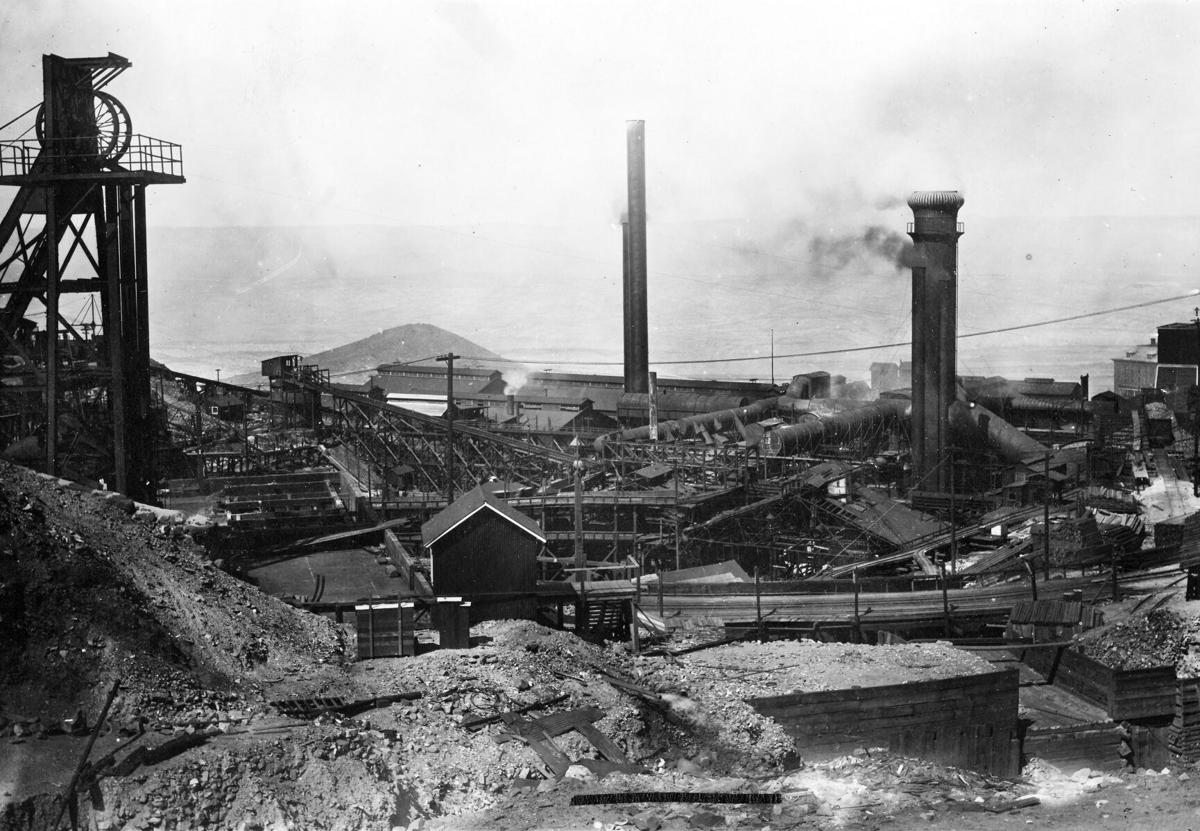

United Verde miners at Jerome congregate around original smelter, circa 1890s.

That year, the spontaneous combustion of unstable sulfide ore in one of the underground mines at the United Verde caught fire due to friction caused by caving. The combustion caused a conflagration in part of the ore body that could not readily be put out by means of flooding or inundating with carbon dioxide due to the vast cracks and vents in the rock structure.

Extreme smoke and heat hindered mining operations in parts of the mine until open pit mining methods were employed in the 1920s to successfully extract the ore from the surface. Some rare hydrated sulfate minerals were formed from this heat including butlerite, guildite, lausenite and ransomite.

The 6,593-foot long Hopewell tunnel measuring 7 by 9 feet was completed in 1908 and helped dewater the United Verde Mine underground operations above the 1,000-foot level. The copper-bearing waters were in turn sent to a precipitation plant so as to separate the copper and other metals in solution to market for profit.

Heightened copper production led to increased burden on the smelter. In 1907, it became evident that a larger smelter to serve the needs of fully exploiting the ore deposits was a necessity.

Additional factors included the smelter’s proximity above miles of underground mining tunnels and its location along the steep hillside, prohibiting expansion. The smelting works began to slip downhill as a result, leading locals to refer to Jerome as “a town on the move.”

Hopewell Tunnel Ore Train

William Clark remedied the matter by purchasing ranches including their water rights 6 miles northeast and 2,000 feet lower in elevation than Jerome along the Verde River.

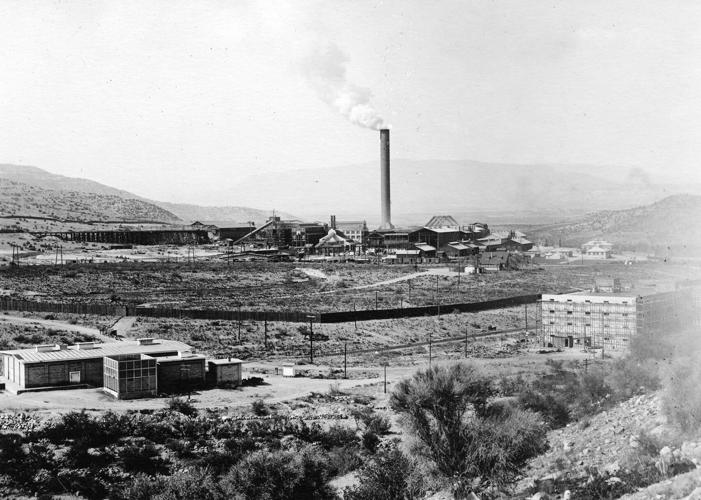

The site was selected based upon access to a water supply, a large clay deposit for stability of a brick infrastructure, accessibility to sand and gravel deposits for construction, proper elevation for slag and tailing disposal, railroad access and the operation of the smelter at a cost of $2 million.

Another factor was the erection of a nearby company town christened Clarkdale, a planned community for the United Verde miners and their families at Jerome.

Work commenced on the new Clarkdale smelter in 1912, culminating in 1915. With a production capacity of 5,000 tons of ore per day, the operation included a crushing and calcining plant along with a Cottrell precipitating plant that included six 100-foot reverberatory furnaces.

A $3.5 million financial advance from William Clark to the Santa Fe Railroad ensured a 38-mile railroad line direct to the Clarkdale smelter from Cedar Glade on the Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railroad. The immediate benefits to the new line were twofold, including the reduction of costs in transporting ore on the steep grades of the old narrow gauge line; and the staffing requirements necessary to transfer freight and express at Jerome Junction from the Santa Fe to the company line.

Depth of the United Verde Mine eventually reached 4,500 feet. Challenges arose that necessitated technological innovation. The burning of sulfide ores over the years hindered mining operations to the extent that open pit mining proved essential to extinguish the fires by the 1920s. The use of timber in stopes employed by the square set method was reduced by employing horizontal cut-and-fill mining methods.

Ultimately, it was the discovery of the United Verde Extension Mine that proved to be the greatest mining achievement around Jerome in the early 20th century. Read about that in next month's installment of Mine Tales, on Oct. 10.

Surveyors employed by the United Verde Mine determine location of new smelter, circa 1907-1910.

Map depicting Clarkdale smelter site and railway connections in 1915.

An Osgood Steam Shovel employed at the United Verde Mine, circa 1920.

The new Clarkdale smelter, circa 1920s.