The line that separates humanitarian aid from human smuggling in Southern Arizona could be redrawn on Tuesday when prosecutors announce whether they will retry a border-aid worker.

Earlier this month, a dozen jurors could not reach a consensus in the trial of Scott Warren, a volunteer with Tucson-based aid group No More Deaths. Warren let two Central American men stay at an aid station in Ajo for several days in January 2018, and prosecutors said he was helping smuggle them to Phoenix. The jury spent three days deliberating before an 8-4 split favoring acquittal.

Now, the decision whether to retry Warren will be the first high-profile choice made under U.S. Attorney Michael Bailey, who was nominated by President Trump in February and confirmed by the Senate in May. The U.S. Attorney’s Office said Bailey was unavailable for comment last week.

Questions linger about why prosecutors decided to make Warren the first border-aid worker in more than a decade to face felony human-smuggling charges in Tucson federal court. Was Warren singled out because he worked with No More Deaths? Did Border Patrol agents simply follow normal investigative leads and end up at Warren’s door?

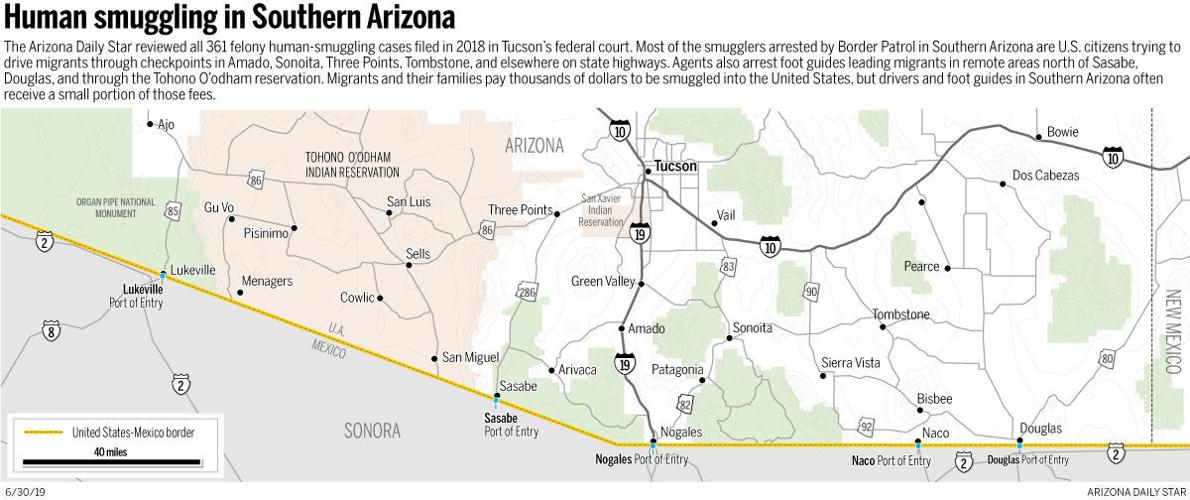

To get a sense of how Warren’s case fits among the typical smuggling prosecutions in Southern Arizona, the Arizona Daily Star reviewed all 361 felony human-smuggling cases filed in Tucson’s federal court in 2018.

The court filings paint a picture of an unruly world where smugglers use ladders to help migrants climb the border fence near Naco, guide them as they walk for days through the desert north of Sasabe, hold them in stash houses in Douglas, or try to pass off fraudulent IDs at ports of entry in Nogales.

Most of all, the court filings show Border Patrol agents arresting smugglers at checkpoints or pulling them over on highways, often with migrants hidden in the vehicle’s trunk. Vehicle stops accounted for nearly three-quarters of the cases in 2018.

In some ways, Warren loosely fits the profile of a migrant smuggler. He was arrested with two people who had crossed the border illegally, a common scenario in prosecutions. He also is a U.S. citizen, as are 80% of the 465 people accused in the 2018 cases.

But Warren, a teacher with a doctorate in geography, breaks the mold in most respects, particularly as one of the only accused smugglers not trying to make a profit.

The other nonprofit smuggler cases here included: a woman who drove to Nogales, Sonora, to pick up her niece but came back to the United States with another girl using fraudulent documents; a seasoned smuggler who did not say he was going to be paid; a man who said he was picking up migrants who paid to cross the border, but he was not getting paid; and a woman who led agents on a high-speed chase before wrecking her car with a migrant inside.

Making money

Judge Raner C. Collins looked down from the bench and addressed Eduardo Valle Robles, a 21-year-old U.S. citizen who said he was paid $300 to drive two Honduran men from a stash house in Tucson to Phoenix.

“For $300, you’re facing between 12 and 18 months in prison,” Collins said at a June 26 hearing. “Does that seem like a good return on investment to you?”

Valle said neither he nor his mother, who was sitting in the courtroom along with his sister and girlfriend, would agree that $300 was worth risking a prison term.

Collins gave Valle a choice: six months in prison or five years of probation. If he violated the terms of his probation, he would face a “heck of a lot more than six months.”

Valle chose probation.

Despite the maximum sentence for human-smuggling ranging as high as 20 years in prison, court records from 2018 show the longest sentence in Tucson’s federal court was less than four years.

Earlier in the hearing, public defender Leo Costales said Valle was a young man who made a mistake. As the only person in his family who was a U.S. citizen, he felt pressure to support them financially.

The decision to smuggle migrants for a few hundred dollars may be dubious in Collins’ estimation, but it is a choice that impoverished residents of Southern Arizona have made numerous times. Defense lawyers often write in sentencing memos that their clients grew up in poverty, were victims of abuse or neglect as children or struggled with drug addiction.

Their small paydays come from the smuggling fees paid by migrants and their families, court records show. In a case from December, a migrant said he paid $7,000 to get to Kalamazoo, Michigan, although that trip was derailed when his smuggler fled the Border Patrol checkpoint in Amado, led agents on a high-speed chase and then started shooting at agents.

Despite the large fees paid by migrants and their families, smugglers in Southern Arizona usually get only a small cut, court records show.

In a case from March 2018, two men said they would get $200 to drive a migrant through the Nogales port of entry using a fake ID. In January 2018, a man pulled over by Cochise County sheriff’s deputies for speeding with two migrants in his car said he was going to be paid $300.

On the other side of the pay scale, a woman in a separate case said she expected to get $4,500 to drive three migrants from a village on the Tohono O’odham reservation to Phoenix.

Warren never was accused of trying to make money when a man from Honduras and another from El Salvador, both in their early 20s, showed up at the building in Ajo known as The Barn. He checked their feet for blisters and called a doctor, who said they should stay off their feet, rehydrate and rest. Both Warren and the two men testified they barely spoke to each other over the next few days.

Prosecutors said Warren conspired with the operator of a migrant shelter in the Mexican border town of Sonoyta to get the men to Ajo, about 130 miles west of Tucson. Warren then conspired with a 67-year-old nurse to keep the men hidden from the Border Patrol, according to prosecutors.

During the trial, federal prosecutor Anna Wright said it was “clear” that Warren was not trying to make money. Instead, his goal was to “thwart the Border Patrol at every possible turn.”

Stash houses

Warren’s case also stands out as one of the relatively few arrests not made on a state highway or in the remote desert.

While No More Deaths described The Barn as a staging area for bringing food, water, and other supplies to places where migrants have died while crossing the border, prosecutors described it as a “stash house.”

Judging by court records, The Barn was the only suspected stash house operating in Ajo in 2018. The most common type of case involved U.S. citizens driving migrants on nearby highways, accounting for five of the eight cases based in Ajo.

The Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector referred questions about stash houses to Homeland Security Investigations, saying, “Much of our border enforcement operations are focused on areas where migrants are either on foot or in a vehicle.”

In response to questions from the Star, HSI said stash houses generally are established north of Border Patrol checkpoints in densely populated communities.

“Ajo would not be an attractive location for stash house operators due to its proximity to the border and few residential communities,” according to HSI.

HSI special agents busted one stash house each in Tucson, Sierra Vista, Ali Chukson and Sells, court records show.

Border Patrol agents made arrests at seven houses in Douglas, two houses in Nogales, one each in Arivaca, Rio Rico and the village of Menagers on the Tohono O’odham Nation.

After their arrests, migrants told agents at least 60 times that they crossed the border and then were taken to a stash house before a driver picked them up. In some cases, agents had residences under surveillance but arrested drivers only after they left the houses.

In Warren’s case, Border Patrol agents set up surveillance of The Barn hours before Warren was arrested. Prosecutors said agents were told migrants were in the area after crossing the border illegally. Warren said it was retaliation for No More Deaths releasing a video that morning showing agents destroying water jugs left for migrants in the desert.

The conditions at The Barn stand in stark contrast with stash houses described in court records.

In Warren’s case, prosecutors showed jurors “selfie” photos of the two Central American men smiling and cooking inside The Barn as evidence they were not in distress or in need of medical treatment, as Warren claimed.

In other cases, prosecutors emphasized the “deplorable” conditions at stash houses.

In a case from September, a Border Patrol aircraft saw eight people enter a trailer in Arivaca. Agents found 13 people from Mexico in the trailer during a search.

“There was no food, and several wanted to turn themselves in,” a Border Patrol agent wrote in a criminal complaint. “The doors were locked from the outside and they could not leave.”

The owner of the property said he was paid $50 for each migrant at the trailer.

In a case three weeks later in Sells, Tohono O’odham police officers were investigating a domestic violence call and found 12 migrants from Ecuador, Mexico and Guatemala inside a building. The owner told HSI special agents she gets $300 for each migrant.

The conditions inside the building were “terrible” and the migrants were held as “virtual prisoners,” federal prosecutor Ann DeMarais wrote in a sentencing memo. “One room was full of rotting garbage, the bathroom was dirty, and the aliens slept on dirty mattresses placed on a concrete floor.”

In a case from November, a Guatemalan man flagged down Tohono O’odham police officers near the village of Ali Chukson. He said he escaped from a residence where he was held against his will.

He directed police, Border Patrol agents and HSI special agents to a house. The owners consented to a search, during which the Guatemalan man’s cellphone was found, along with two firearms.

The Guatemalan man said he had paid to cross the border illegally and ended up at the house, where he “believed they were going to help him get further into the US,” a special agent wrote.

Instead, they told him he had to pay $1,000 per night and hit him when they saw him talking on his phone. The owners expected to be paid $300.

In the courtroom

Nearly 120 people indicted on human-smuggling charges in 2018 were sentenced to probation.

Warren was the only person indicted on human smuggling charges last year to take his case to a jury.

A man and woman were convicted in a bench trial before a judge. Nearly everyone else pleaded guilty or told the court they planned to plead guilty. The few exceptions include those who did not appear for their hearings, one who was deemed mentally incompetent and two whose cases involved kidnapping and a fatal wreck.

For the most part, court records show Border Patrol agents and HSI special agents arresting low-level offenders rather than dismantling smuggling networks.

One notable exception was a case involving 27 defendants running a money-laundering and smuggling network that moved thousands of migrants to more than 30 states, as the Star reported in March. The investigation included more than 4,000 calls and text messages collected by HSI special agents. From stash houses in Phoenix, the smugglers would call migrants’ family members in other states to arrange the rest of the smuggling fee.

That case was the only one that had more court filings than the 292 in Warren’s case.

The pattern among the rest of the cases was about 30 or 40 filings per defendant.

As prosecutors decide whether to retry Warren, he still is waiting for the verdict from a bench trial from May on misdemeanor charges related to leaving water jugs and food in a wildlife refuge in June 2017.