A strong synthetic opioid made by the Sinaloa cartel is increasingly making its way through Arizona, and officials fear a rise in drug-related deaths will follow.

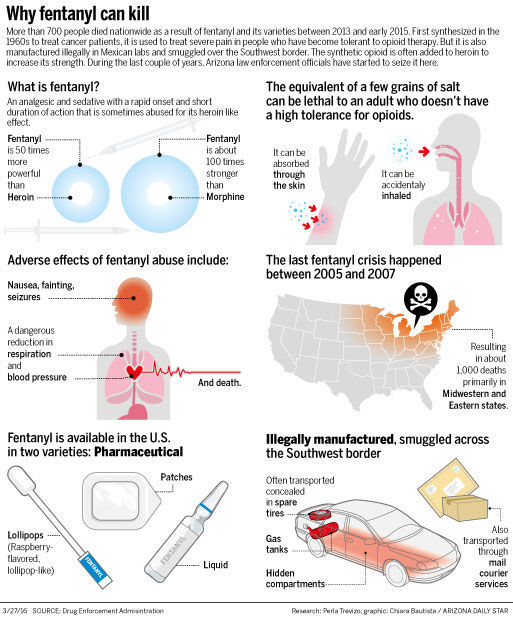

The strongest opioid available in medical treatment, pharmaceutical fentanyl, is used to treat severe pain and is usually administered through a patch. The euphoria-inducing drug is up to 50 times stronger than heroin and up to 100 times more potent than morphine.

Over the last couple of years, more than 700 people have died of fentanyl abuse in the United States, but the real number is likely higher because many state labs and coroner’s offices do not routinely test for fentanyl. Most deaths are attributed to the illegally manufactured version of the drug.

Since 2015, law enforcement agencies in Arizona have made at least five seizures of fentanyl — ranging from 4 ounces to 16 pounds — found inside stash houses and vehicles.

There are about 500,000 potential lethal doses of fentanyl in about 2 pounds, the Drug Enforcement Administration calculates. The equivalent to three grains of salt can be lethal to someone with a low tolerance.

“Fentanyl can put people to sleep to the point they can stop breathing,” said Greg Hess, chief medical examiner in Pima County. “Because fentanyl is more potent, the window or margin of error might be less for someone not as experienced.”

Only a small amount is needed of the illegal powder fentanyl cartels make to mix with heroin to make it stronger. Nationwide, persons dying from fentanyl are mostly heroin users exposed to fentanyl without knowing it.

There is no state data on fentanyl-related deaths, but the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner reported an increase from seven overdose deaths where fentanyl was listed as a contributing factor in 2014 to 17 last year.

“But what it means in the larger scheme of things, I don’t know,” said Hess.

The numbers include all overdose cases from Cochise, Santa Cruz and Pinal counties and additional cases from eight other counties.

During this time, there were only two deaths where combined heroin and fentanyl toxicity was listed as the cause of death. Medical examiners can’t distinguish between the pharmaceutical fentanyl and the illegally manufactured fentanyl smuggled through the U.S.-Mexico border.

But as the seizures continue, officials said it’s only a matter of time before the potentially deadly fentanyl-laced heroin makes its way here.

• • •

Reuven Shorr and his brother, Ezra, born four years apart, were best friends.

|

Growing up, Ezra tried to mimic whatever he saw his older brother doing. If Reuven bought new sneakers, Ezra wanted a pair. If Reuven played basketball, Ezra would play too.

“He would always want to tag along with my friends,” said Reuven, 31, who has his brother’s name tattooed across his knuckles.

They grew up with two loving, caring college-educated parents, he said.

The years are fuzzy to Reuven, who is on methadone to recover from his opioid addiction, but both brothers started taking painkillers more than a decade ago. First, buying them on the street, then a combination of prescribed and illegally obtained.

“I knew how to play the game,” he said.

After he got in a car accident, Reuven found a doctor and pretended to be in much more pain than he actually was.

“I bought a cane and would walk into the room as if my back was really hurting,” he said, and would leave with the dose and type of pill he had hoped for.

After he lost his job and his wife because of his addiction, he moved in with his brother. They would get high and play video games all day.

Their addiction got so bad they ended up selling everything they owned to get their fix.

As it is for many addicts, once they could no longer afford the pills, they switched to heroin and at some point were introduced to the fentanyl patches because they were stronger.

“You are always chasing that one feeling that you are never going to get,” Reuven said.

He said Ezra was mixing a combination of drugs, depending on what he could afford that day, including those prescribed for his depression and mental health disorders. Reuven is not sure when Ezra started abusing the fentanyl patches.

“If he’s taking fentanyl I don’t know because it can be on his hip,” he said. “If we are smoking or popping pills, I see it.”

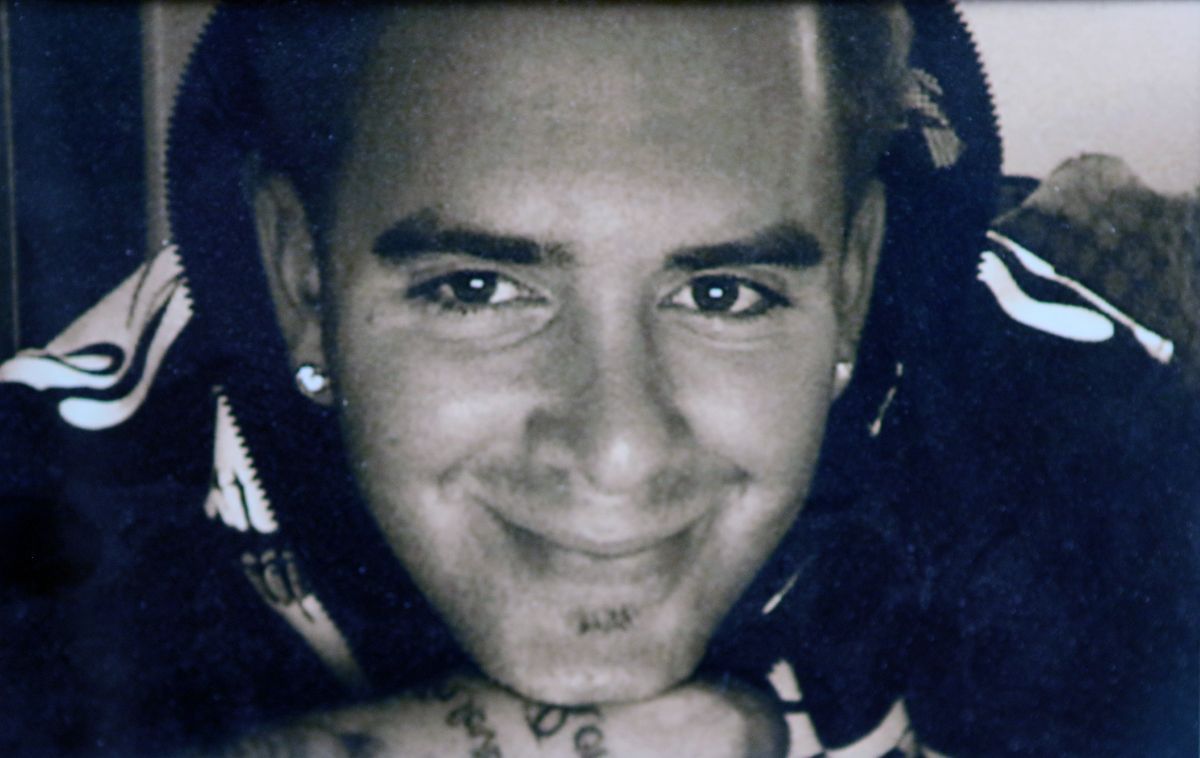

Ezra, 26, was found dead on Nov. 20, 2014, in the side yard of his mother’s home. The cause: acute combined drug intoxication including fentanyl, oxycodone and Ecstasy.

Reuven later found a stash of fentanyl patches in a safe.

At least six of the 24 fentanyl-related deaths seen by the Pima medical examiner and reviewed by the Arizona Daily Star note a fentanyl patch in the autopsy report.

Many of the several dozen cases seen at the Arizona Poison and Drug Information Center related to fentanyl have to do with the patch, said the center’s director, Keith Boesen.

“It’s a highly concentrated opiate,” he said, and absorption can be affected by things such as heat exposure or people forgetting to take it off after the third day.

That happened to Reuven Shorr once. “I didn’t remember I hadn’t taken the patch off and was using a bunch that day and was so high I couldn’t figure out what was going on.”

Other people have cut the patch open to put a small amount directly inside their mouths, Boesen said.

Fentanyl is often used to treat chronic pain, and it’s a good medication when used appropriately, he said. One of the benefits of using fentanyl as opposed to other opiates is that smaller doses can have the same effects. The patch is designed to deliver the drug consistently over three days.

Another advantage is that when administered intravenously for a short surgery, it acts very quickly but the effects don’t last too long, Boesen said.

But because of its strength, it can also be deadly. Eighty percent of the 24 deaths recorded by the Pima medical examiner were ruled accidental, with four suicides and one undetermined.

The list includes people ages 26 to 66 years. The dead were firefighters and paramedics, college graduates, outdoor enthusiasts and recovering drug addicts. There were middle-age men and women, most found dead by their loved ones, often in their beds.

A 50-year-old from Colorado was found face down on a cactus with three patches on him. His obituary said he died doing what he loved most, hunting rocks in the Arizona desert.

Most of the deaths involved fentanyl mixed with other drugs — both prescription and nonprescription — including oxycodone.

The Centers for Disease Control issued new guidelines for prescribing opioids and the Federal Drug Administration now requires a “black box” warning about the risk of abuse, addiction, overdose and death of painkillers such as oxycodone and fentanyl, in an effort to help slow the prescription drug abuse epidemic.

This year, Shorr completed peer support specialist training to council others about rehab and available services.

“I’m applying for positions so I can meet people and families from all walks of life to talk to them,” he said. “But most importantly, to listen and help them with advice or resources so I can avoid as much as possible another situation ever happening like what happened to my brother and happens to people every day.”

|

Three months before his brother died, Shorr went on methadone, which is an opioid but is also used to treat addiction, after he says he realized he couldn’t get clean just by going to rehab.

If it weren’t for that, he said, he probably would be dead. But Ezra was never interested in rehab or treatment, even after a number of overdoses.

“You can’t make someone quit who doesn’t want to,” Shorr said.

Ezra’s death, he said, changed his family forever.

His father, a renowned artist and photographer, “finds very little happiness in his normal day-to-day life,” Shorr said.

“It’s a lot harder to explain with mom. I can see in my mom’s eyes that she’s missing something, even when she’s smiling,” he said, trailing off.

“I miss having conversations with him about things I can’t with anyone else, not because it’s a secret, but because I’m only interested in his opinion.”

•••

While the share of fentanyl-related poisonings and deaths in Arizona is small compared with other opioids, what worries local law enforcement and medical officials the most is the illegal fentanyl made in Mexico.

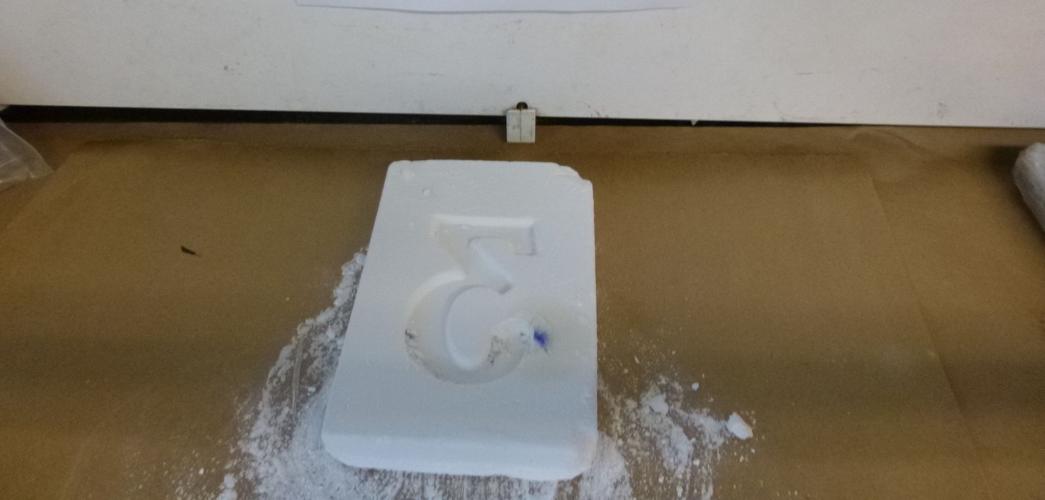

In 2014, a 35-year-old Tucson resident was found unresponsive in a Tempe hotel with white foam coming out of his mouth and nose. A plastic bag with a large amount of white powder was found in the room. It was later identified as fentanyl.

“For a guy to take fentanyl and snort it as if it was coke or something like that, I’m pretty sure he didn’t know what he had in his hands,” said Doug Coleman, DEA special agent in Phoenix.

“In the past, we’ve had offshoots and isolated incidents where fentanyl raised its ugly head in the heroin-user community,” Coleman said, but it was normally one particular batch or a particular trafficker.

Between 2005 and 2007, over 1,000 deaths nationwide were attributed to fentanyl, concentrated in Chicago, Detroit and Philadelphia. The source was traced to a single lab in Mexico, and when that lab was dismantled the surge ended, the DEA said.

Now, fentanyl is seized and distributed throughout the country as opposed to specific hot spots, Coleman said.

|

“What we are seeing now is fentanyl added to these heroin batches or sent in specifically to try to raise the price of the product or to get people hooked,” he said.

Last November, Tucson police raided a stash house where they made four arrests and seized 18 weapons, cash, cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine and what turned out to be 2 ounces of heroin cut with fentanyl and 4 ounces of pure fentanyl.

Initially there was nothing unique about the raid, said James Scott, a lieutenant with the Tucson Police Department Counter Narcotics Alliance, besides the number of firearms.

“We suspected a large chunk of drugs we found were meth, but turned out to be fentanyl,” he said.

The department knows a lot of the drugs that end up back East come through the Arizona-Mexico border, he said, but it hadn’t seen fentanyl until last year.

In February, an Arizona Department of Public Safety trooper seized 15 packages with about 16 pounds of fentanyl powder during a traffic stop on Arizona 87 at Milepost 118.

Lacing heroin with fentanyl gives traffickers an advantage for selling the strongest stuff, the DEA’s Coleman said.

“There’s no question that Mexican cartels will get more involved in the fentanyl trade,” he said. “For sure we are going to see them manufacturing pills, and for sure we are going to see some of those pills sent here.”

TPD already had its first. A few months ago the department seized a batch of pills branded as oxycodone, which Scott said was fentanyl.

In other parts of the country, a rise in fentanyl seizures has coincided with an increase in fentanyl-related deaths.

The number of fentanyl drug seizures reported to the National Forensic Laboratory Information System rose from 618 in 2012 to nearly 4,600 in 2014. In Arizona, as of March 16, fentanyl drug seizures went from two in 2011 to 25 in 2015, but represented less than 1 percent of overall drugs reported.

The recent seizures are tied to the rise in heroin being trafficked through Arizona, Coleman said.

Since fiscal 2010, the amount of heroin seized in the state jumped more than 250 percent, from 359 pounds to 1,272 last year.

“The difference is that people, generally speaking, aren’t smuggling 100 kilos of fentanyl at a time,” Coleman said. “It’s coming in smaller quantities,” which makes it harder to find.

Customs and Border Protection data from the country’s ports of entry show at least 16 seizures in the past five years, most of them of a few ounces each, although there are exceptions, including a 29-pound fentanyl seizure in New Orleans in fiscal year 2015.

Another concern regarding the powder fentanyl is the risk to first responders because it can be absorbed through the skin or accidentally inhaled.

TPD is already educating officers on the potential dangers of fentanyl, Scott said.

Trying to get ahead, the department is looking to buy field test kits and naloxone to treat overdoses, he said. It is also reminding officers of the importance of wearing gloves and to call the counter narcotics alliance unit if they go into a house and they think there’s fentanyl.

“What happens on the East Coast typically ends up here also,” Scott said. “It’s just a matter of time.”

• • •

Fentanyl should not be seen as a unique problem, but as a feature of the heroin epidemic fueled by prescription painkillers, officials said.

“People need to realize that nobody wakes up in the morning wanting to become a fentanyl addict, but it’s a progression that starts with people taking prescription drugs different than they are supposed to, not under a doctor’s supervision and diverting those things,” the DEA’s Coleman said.

In 2014, doctors wrote 6.6 million legal fentanyl prescriptions. “Opioid-based prescriptions led us to this problem and a massive increase in those prescriptions is what’s taking us down this path,” he said.

From 2000 to 2014, nearly half a million people died from drug overdoses in the United States. More than half in 2014 involved some type of opioid, including heroin.

Some of the worst-hit areas are places like New Hampshire, which ranks third highest for per capita drug deaths nationwide. Fentanyl is killing more people there than heroin.

|

Elizabeth Stabler was from Hollis, New Hampshire. Described by friends and family as artistic and an animal lover, she played the guitar and flute and liked to travel. She graduated in 2009 summa cum laude with a degree in anthropology and sociology from Appalachian State University in North Carolina.

Her social media page is full of pictures of her with animals and friends. Some are of her in her garden.

She was the type of person you could just have long conversations with, said long-time friend Heather Oliver. “She always said something that made me think.”

But she had a hard time finding a job, said her uncle, Ken Brown, from New Hampshire. She worked as a barista and with AmeriCorps, which didn’t last very long.

She returned to New Hampshire where she started dating a man who got her hooked on drugs, said Oliver, who first met Stabler in middle school.

Stabler came from an upper-middle-class family. Her father was a Harvard graduate and software engineer. “But she was not able to get away from what I would call the generalized pain of living,” Brown said. Her mother died when she was in middle school, and her father died in 2012 due to complications of diabetes, according to his obituary.

“Both things had caused her pain she couldn’t get over, and she numbed herself with drugs,” he said.

After a stint in rehab in New Hampshire, she moved to Tucson, where she had heard good things about a treatment center, Brown said.

On Christmas 2013, she posted on her Facebook account: “Merry Christmas to all! I am finding myself in Tucson Arizona, making a new life down here, and sitting in the 60 degree sun! Unreal :) Sending lots of love and to those I’ve been out of touch with, I will be in touch soon! Miss you,” followed by three pink hearts.

There had been progress before her death, Brown said, “but the last month she had cut herself off from her brother and the rest of the family, and we were getting concerned when we were not hearing from her.”

Stabler, 32, was found dead on Nov. 21, 2014 — that month there were three fentanyl-related deaths recorded by the Pima medical examiner, including Stabler’s and Ezra’s.

Stabler broke into a motel room where her boyfriend, who had previous drug arrests and was in jail at the time, lived. She was found in the bathroom with a spoon with burn marks and residue in her purse.

“I don’t know if she had any reason to believe it was more potent,” Brown said.

Stories like Stabler’s need to be told, he said, because this can happen to anyone.

“For anyone who knew her, you wouldn’t look at her and say, ‘Oh, my God, she has a drug problem,’ ” Oliver said.

“She was so active with her art, she wrote a lot, she had so much going on that you never knew she had a problem.”

Not even Oliver knew much about her addiction.

“She was one of my closest friends, but there was a part of her I never got to see,” she said. “We never talked about that.”

Society’s best bet against this epidemic is education, Brown said.

“The family has to be constantly vigilant, and even sometimes that’s not enough. I don’t think the children can be too young when you start to talk about it,” he said.

“Once someone becomes addicted it is so dominating, it’s very hard to combat it,” he said. “I won’t say it’s too late because there are people who have recovered, but it makes the struggle tougher.”

|