Police militarization became an issue of national debate as Americans watched heavily armored police crack down on protesters after the Aug. 9 shooting of an unarmed black teenager in Ferguson, Missouri.

Now some local law enforcement officials are reconsidering their own tactics and interactions with the public.

“Militarization of the police has been pushed more and more to the forefront. Is there a warrior-guardian type mind-set that we need to be cautious of?” said Chris Nanos, chief deputy of the Pima County Sheriff’s Department. “You would be remiss if you didn’t look at those events and say, ‘Could that be us?’ And then do what you can to learn from it and not be in that position.”

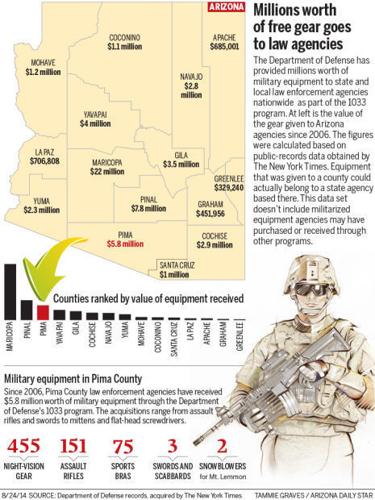

The Department of Defense’s 1033 program and other federal programs have helped supply local police with assault rifles, armored vehicles, night-vision goggles and other military equipment since the 1990s. Pima County law-enforcement agencies have received $5.8 million worth of military gear through the program since 2006, according to Defense Department records obtained and shared publicly by the New York Times.

The data set breaks down the 1033 military transfers by county, but not by law enforcement agency. It does not include military equipment agencies acquired through other programs or purchases.

Nationwide, 500 law enforcement agencies used federal programs or grants to acquire mine-resistant, ambush-protected vehicles that can withstand roadside bombs, says a June report from the American Civil Liberties Union that focused on the militarization of American police.

“Using these federal funds, state and local law-enforcement agencies have amassed military arsenals purportedly to wage the failed War on Drugs, the battlegrounds of which have disproportionately been in communities of color,” said the report, which called for greater oversight of programs like 1033, and more judicious use of heavily armed SWAT teams, which are now routinely used to carry out search warrants in homes.

Last year, four local police agencies settled a lawsuit with the family of Jose Guerena, a former U.S. Marine who was killed in 2011 during a drug raid by a Pima County Regional SWAT Team.

Guerena’s wife woke him as the raid began, saying she thought intruders were in the yard. Guerena, 26, came around the corner into a hallway holding his AR-15 rifle and SWAT officers shot at him 71 times, hitting him 22 times, the Star reported at the time. The lawsuit alleged the SWAT team acted negligently.

WHAT AGENCIES GOT

Law enforcement in Arizona counties — Gila, Mohave, Navajo, Pinal, Yavapai, Yuma and Maricopa — have 11 mine-resistant vehicles obtained since 2006 through the 1033 program, which was launched in 1997 and gave preference to agencies engaged in counterdrug and counterterrorism activities.

Maricopa County alone got four of them, plus more than 400 assault rifles, seven other armored vehicles and five helicopters. The Defense Department records include equipment transfers to state agencies that happen to be based in a given county. Maricopa, home to the state Capitol in Phoenix, is also the headquarters of most state agencies.

Pima County agencies’ military transfers through 1033 include 455 night-vision optics such as goggles and scopes, 282 pieces of body armor like vests or helmets, and 151 assault rifles. Among the other acquisitions in Arizona since 2006: Navajo County got dozens of rifles; a rubber, an inert grenade launcher for training purposes; and three night-vision sniper scopes. Gila and Yavapai counties have two armored trucks each. La Paz County got 43 assault rifles.

“Arizona law enforcement, designed to serve and protect communities, is instead equipped to wage a war,” the ACLU report said.

Actually, much of the gear coming to the Tucson Police Department through 1033 is medical supplies, personal protective gear, cases and pouches for police tools, and storage equipment, said Mark Timpf, Tucson police assistant chief.

The department did get at least 50 M16 rifles from the program, but because military rifles are fully automatic and the Police Department uses semiautomatic rifles, TPD uses them only for parts.

Tucson police don’t have any firearms more powerful than what criminals are using, Timpf said. Although violent crime is down in Tucson, the intensity of the violence has increased, he said.

TPD also got 13 Humvees through 1033. One is an armored Humvee the SWAT team uses to provide cover and rescue when a victim needs to be moved under the threat of gun violence. Four are used for parts, and eight mostly sit in storage but are available to specially trained units for search and rescue, Timpf said.

The Oro Valley Police Department received 20 M16s last year and got an armored vehicle in 2000. Crime rates are low in Oro Valley, but spokeswoman Lt. Kara Riley said, “We have to prepare for the possibilities, not just the probabilities.”

In April, Oro Valley PD deployed its armored vehicle after a man fled the scene of a traffic stop. Steven Wahl entered an Oro Valley home, barricaded himself and took several people hostage. A standoff with the Pima County regional SWAT team ensued, and Wahl eventually shot and killed himself. That night, “that vehicle absolutely saved lives,” Riley said.

The 1033 program also saves taxpayer money, TPD’s Timpf said. Equipment acquired through 1033 is equipment agencies don’t have to buy.

That’s particularly important in rural areas like Navajo County, where resources are stretched thin, said Navajo County Sheriff’s Department Chief Deputy Jim Molesa. The department received 70 M16s, which would otherwise cost $1,200 apiece. He said the department shares its mine-resistant vehicle with other agencies, like the regional SWAT team.

“When somebody is giving something away for free, people generally take it,” Molesa said.

CONCERNS OVER GEAR

Most of the 1033 transfers to the Pima County Sheriff’s Department include gear such as warm socks, tools, rope and webbing materials for search-and-rescue teams, Chief Deputy Nanos said. One especially useful transfer was military-grade first-aid kits, which were used during the Jan. 8, 2011, shooting of then-Rep. Gabrielle Giffords and 13 others, he said.

The Sheriff’s Department has armored vehicles bought with federal grant funding, not the 1033 program, Nanos said. But the department did not want a mine-resistant vehicle.

“I can’t imagine its use,” he said. “A 28-ton vehicle? I don’t know if I would even want that on the road.”

The Sheriff’s Department plans to boost oversight of its acquisitions through 1033 and similar programs to ensure the equipment received is truly useful, he said. It also is increasing oversight of the use of SWAT teams.

What happened in Ferguson serves as an important reminder that combat-style dress and firepower can escalate tense situations, Nanos said.

“If you dress for a riot, they’ll come,” he said. “We do need to be prepared and be well-trained and equipped for those rare moments you may have to use some brute strength. … But 99 percent of the time, our law enforcement effort is really a communication effort. How do we become problem solvers? Not everything needs to be solved with muscle.”