An NPR story about astronomers being “boys with toys” triggered a Twitter-storm response from women in astronomy and other sciences this week.

Joe Palca’s Saturday edition of “Joe’s Big Idea” featured Caltech astronomer Shrinivas Kulkarni, who said, “Many scientists, I think, secretly are what I call ‘boys with toys.’ ”

That didn’t sit well with the women who help build, operate and direct some of the largest astronomical facilities on Earth — and in space.

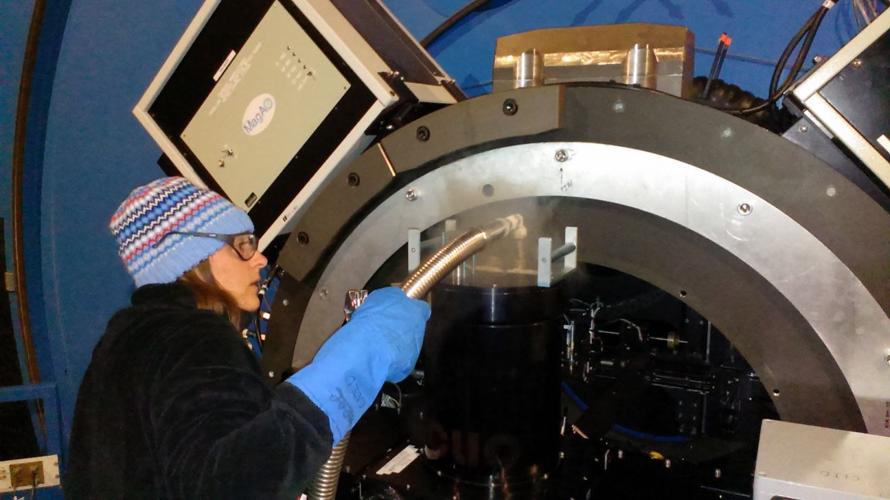

Using the hashtag #girlswithtoys, they posted photos of themselves with their toys. There were more than 11,000 tweets by Monday.

The response, much of it light-hearted and celebratory, also had a more serious undercurrent, and with good reason.

Women make up 48 percent of the overall work force in the United States, but only 24 percent in the STEM occupations of science, technology, engineering and math, according to a U.S. Department of Commerce analysis of the 2010 Census.

Multiple studies show that gap is similar or worse for graduate students and faculty at U.S. universities, particularly in engineering, physics and computer science.

But while the problems are real, the Twitter explosion was mostly in fun, said Katherine Alatalo, a post-doctoral at the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center at the California Institute of Technology.

“It was a celebration of scientists who happen to be women,” she said.

Alatalo, who knows Kulkarni, said she, and most of the women scientists who responded, did not take total offense at his “off-the cuff comments.”

“I know Shri. He has actually shepherded some of the most successful women in astronomy. There are a lot of words you could use to describe him, but ‘sexist’ is not one of them.”

She welcomed the backlash, though. “The reason you need it is that there are still incidents of sexism — all the way up to much seedier things.”

Alatalo and Heather Flewelling founded a group called Astronomy Allies, to make it easier to report instances of sexual harassment at astronomical conferences and elsewhere, after seeing a report of widespread unreported abuse in a survey of field scientists in other disciplines.

“Allies sprung from this understanding that the culture allowed these few, but powerful, bad actors to run rampant,” Alatalo said.

Alessondra Springmann, an asteroid expert who is currently working with NASA’s OSIRIS-REx project at the University of Arizona, said she had never experienced any antipathy toward women in her under-graduate and graduate studies, but found “in the field, you start encountering attitudes that are a little medieval toward women.”

In terms of representation, there are "even deeper problems" with people of color and gender minorities, she said.

Springmann said she enjoyed the Twitter controversy but worried that it might send a wrong message about scientists playing with “toys.”

“These are serious scientific instruments that require years, if not decades, to develop. These things are expensive and are funded by the taxpayers,” she said.

Lori Allen, an associate director of the National Optical Astronomy Observatory and director of Kitt Peak, said Kulkarni’s comments were “unfortunate and kind of dumb,” but she, too, did not think he had sexist intent.

Allen, who has worked in astronomy for 30 years, also said that telescopes, like the 25 currently operating on Kitt Peak, are “tools, not toys.”

“They are built to very technical specifications and we employ these instruments … to understand better the origin and evolution of the universe.”

That understanding is being sought, more and more, by women, she said. A recent conference hosted by NOAO on how to handle big data in astronomy was evenly divided between men and women participants, she said. “You certainly would not have seen that 30 years ago.”

Astronomers dominated the Twitter conversation, but the photos included biologists handling rattlesnakes, geologists measuring glaciers and lots of laboratory scenes.

University of Arizona physics graduate student Sarah Louise Jones sent a photo of herself helping to upgrade an instrument for the ATLAS detector for the Large Hadron Collider, pretty much the biggest scientific instrument on Earth.

Jones helped form Women in Physics at the UA in 2013.

It offers outreach and seminars to boost the numbers of women in a field.

“Before graduate school, I really didn’t think a lot about having classes where I was the only female,” she said.

Now she wants to do something about it.

“One of the things we’re trying to do is recruit and retain female graduate students,” she said.