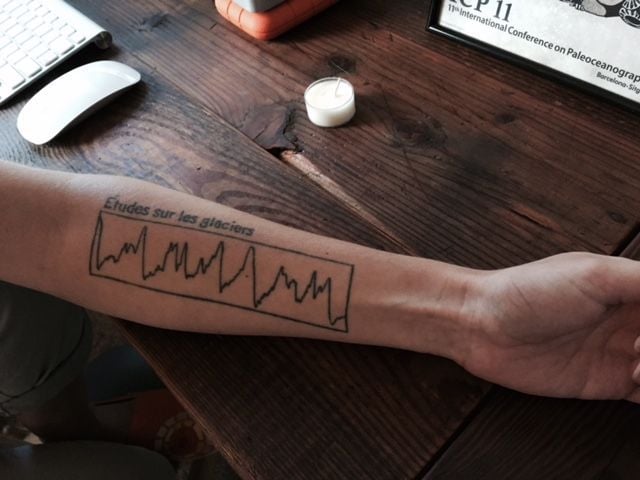

Jessica Tierney wears her passion for climate history on her left forearm.

There, a tattoo depicts the glacial history of the Earth in the form of a graph, reconstructed from evidence in cores of ocean sediments.

It is inscribed: “études sur les glaciers,” (study of the glaciers) the title of a seminal book on glaciation by naturalist Louis Agassiz.

Tierney, 33, was appointed in May as an associate professor in the University of Arizona’s Geosciences Department. She is a paleoclimatologist — a field that began with study of the Earth’s ice ages.

The field allowed her, as an undergraduate and graduate student at Brown University, to combine her love of history with a growing affinity for scientific research.

Tierney is also an organic geochemist, who performs analysis of hydrocarbon compounds contained in cores of sub-ocean sediments to construct her climate histories.

Most recently, she and paleo-oceanographer Peter deMenocal challenged the hypothesis of climate modelers who said the countries of the Horn of Africa — Ethiopia, Somalia and Djibouti — would get wetter as global temperatures increased.

They found evidence in the modern instrumental record and verified it in sediments that deMenocal and a team of scientists had gathered in the Gulf of Aden that the exact opposite had happened, is happening today and will probably occur in the future.

“Sometimes what the models say will happen isn’t reality and the only way we can constrain future (climate) is with the past,” Tierney said.

Julia Cole, a paleoclimatologist and professor of geosciences in the department Tierney has joined, said Tierney’s reconstructions are important. “We don’t have very many sources of observations about climate change over long time periods, especially in places like the Horn of Africa.”

Cole said Tierney is “pioneering the use of organic tracers” in paleoclimatology. “She really is a star,” said Cole.

Tierney’s star status was recently recognized by the Packard Foundation, which awarded her a five-year fellowship, designed to allow early-career scientists to pursue novel areas of scientific investigation, by giving them $175,000 a year for five years.

In Tierney’s case, said deMenocal, the award will keep her from “being thrown under the wheel of this anti-climate-science sentiment in the federal government.” DeMenocal was Tierney’s professor and mentor during her postgraduate stint at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

It is tough for Tierney and other climate researchers to win grants for basic research these days, he said. In the field of paleoclimatology, the success rate of grant proposals has plummeted from 30 percent to less than 10 percent in recent years, deMenocal said.

The Horn of Africa study, funded by the National Science Foundation, was published this month in Science Advances, the open-access, online spinoff of the journal Science.

To arrive at precipitation totals for the study, Tierney used the simple hydrocarbons of waxy plants to find the ratio of light and heavy hydrogen (deuterium) in core samples over a 2,000-year span.

Heavy hydrogen falls more easily from clouds and dominates the record in dry years, Tierney said. In wetter years, the ratio of lighter hydrogen is greater.

To determine relative temperatures of a given span of years, she examined archaea, microorganisms which add protective structure when temperatures are warmer.

The Packard Foundation Fellowship will give her the freedom to pursue similar studies of cores from the Gulf of California, Tierney said.

She wants to see what they will tell her about the imperfectly understood North American Monsoon — important to Southern Arizona because it brings us half our annual rainfall; even more important in Sonora, where it can account for up to 70 percent of annual precipitation.

Knowing how that will change in a warming world is important to planning our water future, she said.

“We’re hoping we can get a very specific picture of the monsoon season,” Tierney said.

“Some probability models show the Southwest will get very dry in response to global warming,” Tierney said. “We don’t know how the monsoon will react. There is a lot to learn there.”

Tierney also wants to complete the “story” told by her molecular investigations by finding a way to turn her qualitative findings into real numbers.

“It becomes a little bit of storytelling where we say, “Well, we think this happened and it was warmer or cooler or it was wetter or drier.’”

Learning and applying some sophisticated mathematical probability models could allow her to turn those ratios into numbers, she said.

Her third goal is to apply those quantitatively evolved measurements to future climate.

“It all kind of leads together where you’re creating the data and creating the statistical frameworks which come together again to tell us how the Earth system works that’s new and can potentially help us to understand what climate will be like in 50 or 100 years or beyond that.”

It could be tricky. You can find Earth epochs where carbon dioxide levels, the drivers of global warming, are the same as today, but you have to go back 4 million years, she said.

“That’s before modern humans were around, so, as a species, we’ve never seen this climate and we’re not adapted to this.”

Also different about our current era is that the rate of change is so fast, she said.

“There is no perfect analog for what we’re doing to the planet right now — there really isn’t,” she said.

Peter Reiners head of the Geosciences Department, said “understanding paleoclimate back through time is the only way were going to understand what we’re in for. There are undoubtedly big surprises in store for us that we don’t really understand right now.”

Tierney’s skills fill a niche in his department’s and the university’s exploration of those topics, he said.

“We’re just really excited that the Packard Foundation shares our enthusiasm for Jess’s work and her potential,” Reiners said.

The freedom created by the Packard Award instantly increases her productivity, said Tierney.

“It relieves the pressure to seek funding — to write as many proposals to other places to get money — because the time you spend writing proposals is time you could be spending researching.”