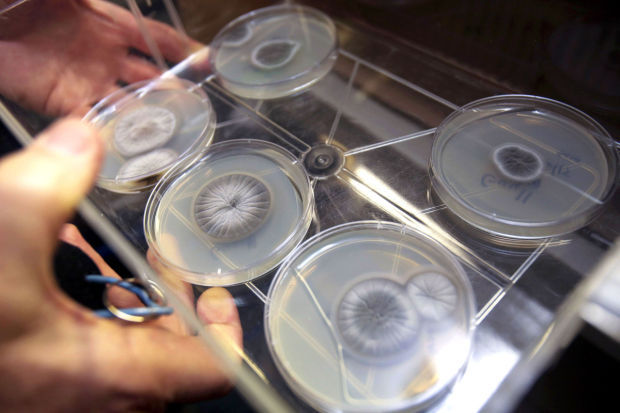

New technology could reveal the microscopic, sometimes deadly spores that cause valley fever that currently float in the air undetected.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is developing a sensor that can detect levels of the cocci fungus in the air and soil, said Christopher Braden, deputy director of the CDC’s National Center for Emerging Zoonotic Infectious Diseases branch. The agency has been working on the technology for three years, and Braden is hopeful the sensors could be moved into wider use over the next few years.

“As far as we know, we’re the first ones who have been able to find the right combination of preparing the sample and the molecular test itself to be able to detect the organism in different soil and air samples,” Braden said.

The CDC has adapted vacuum devices typically used by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to detect levels of hazardous materials in workplaces. These devices are placed in areas with dry soil, where they pull in air at regular intervals and test it for the DNA of the fungus. The level of fungal spores in the air is then sent to a central computer.

If the technology could be deployed throughout endemic regions of the Southwest, it could provide a breakthrough in awareness and prevention efforts, local health officials said.

A “huge” warning tool

As it stands, health officials can only warn people to take caution on windy days, or when the air quality forecast hits unhealthy levels.

“It’ll be a huge tool to put in our tool box,” said Kirt Emery, a Kern County Department of Public Health Services epidemiologist, who quickly rattled off all the ways that technology could prevent cocci’s spread in the nation’s most impacted regions.

The devices could confirm whether cocci is stirred up by construction and agriculture, as experts have for years suspected. During storms, a color-coded air quality alert could be issued just for cocci. If the technology is advanced enough, fungus from Sharktooth Hill, a valley fever hotspot in California, could be traced to see how far it travels on windy days. Eventually, a mass alert could be developed that pings cellphones when people enter certain regions on high-risk days.

The technology could also shorten the time lag between when health officials realize there’s an outbreak and when they warn the public, said John Galgiani, director of the Valley Fever Center for Excellence at the University of Arizona.