For the first time since May 2012, the state will accept applications for medical-marijuana dispensary licenses this summer.

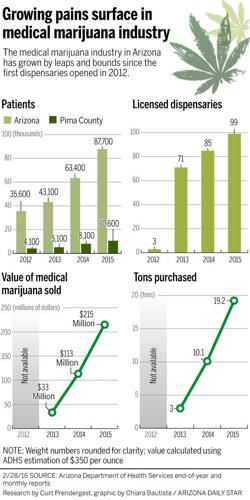

The announcement by the Department of Health Services comes as Arizona patients spent $215 million on 19 tons of medical pot last year, nearly double the 10 tons purchased in 2014.

Even with record-breaking sales, lawsuits filed by business partners alleging breach of contract, mishandling of funds and other corporate malfeasance hint at cracks in the industry’s foundation.

The lawsuits filed in Pima County and elsewhere in Arizona stem from a variety of root causes, industry insiders say, such as Arizona being one of the few states to use a lottery to award dispensary licenses or speculators bringing together a hodgepodge of ill-suited partners.

But others say lawsuits are bound to happen in a nascent industry, particularly one centered on a quasi-legal substance that is shut out of the normal financial world.

Medical-marijuana dispensaries are “extremely hampered” by a lack of easy access to banking services, said Scottsdale-based business lawyer Richard Keyt.

“It opens the door to tax fraud, embezzlement, theft and all kinds of bad things,” he said.

At the Downtown Dispensary in Tucson, one of the directors accused the board of failing to track cash transactions, misusing company funds and removing a director without notice. The claims were dismissed, but are being appealed, Pima County Superior Court records show.

In Marana, the Nature Med dispensary hired Trance Industries to grow marijuana at the dispensary. But insufficient electricity meant Trance Industries couldn’t grow the agreed-upon amount, according to a Feb. 8 lawsuit.

The agreement fell apart, and Trance Industries accused Nature Med of selling $140,000 of marijuana from 1,100 plants without compensation.

The former manager of a Tucson dispensary sued the board members of a dispensary in Globe for $1.1 million, saying they made a deal behind his back to force him off the board, as the Star reported Jan. 29.

Gold rush and

lottery “winners”

The chance to make big money in Arizona drew a “gold rush” of consultants from the medical-marijuana industries in California and Colorado, said Vicky Puchi-Saavedra, owner of Tucson dispensary Earth’s Healing.

Those consultants gathered investors and promised huge returns, she said.

The consultants told investors: “‘Come on in, it’s going to be easy as pie. Once we get that license, that golden ticket, everybody is going to get super-rich, super-easy,’” she said.

“It’s not as easy as it looks.”

Instead of joining up with strangers, Puchi-Saavedra took out high-interest loans, rented property and started her own cultivation site.

With the upcoming round of dispensary licenses, “my advice to investors is to make sure you know who you’re investing your money with,” she said.

Arizona has one of the largest of the 24 medical-marijuana programs in the country, with 91 nonprofit dispensaries serving 89,000 patients, including more than 10,000 in Pima County, according to Arizona Department of Health Services reports.

The 2010 voter-approved medical-marijuana law prohibits the ADHS from publicly disclosing dispensary locations. Informal counts by industry groups show about a dozen dispensaries in Pima County.

One dispensary license is allotted for each of the state’s 126 health districts. When the state issued 99 licenses in August 2012, officials used lottery balls marked with application numbers to award licenses in districts with more than one applicant.

The state received nearly 500 applications, but none for 27 districts, including one in Tucson. Eight of the licensees are not operating dispensaries.

Applicants needed local zoning approval, appropriate facilities, $150,000 on hand, and a criminal-record check, among other requirements.

A similar selection process will be used this time around, ADHS officials said, except for the $150,000 requirement that was removed in December 2012.

Officials are staying mum on how many licenses will be issued and when exactly the lottery will take place, but they said details will be released at least 30 days in advance.

The lottery is one reason Arizona is more prone to legal disputes than many other states, said Kris Krane, president of Phoenix-based 4Front Ventures and a medical-marijuana policy advocate in California, Arizona and elsewhere for 20 years.

“A lot of the groups that won licenses were really not qualified to operate,” Krane said.

Many dispensary directors did not know each other or how to grow marijuana, he said. As a result, dispensaries and growers joined in “shotgun marriages.”

The owner of a dispensary in Williams cut off an agreement with a cultivator nine months after signing it. Security cameras then recorded the owner chopping down the cultivator’s plants and loading them into an SUV, according to a Jan. 8 lawsuit filed in Pima County.

The cultivator, Agricann, put the value of the plants at $500,000, said Agricann’s attorney Patrick Van Zanen.

Most attorneys in local lawsuits did not respond to requests for comment or would not comment.

In some cases, companies burned through their startup money and took on more investors, which led to even more disputes, Krane said.

Court records show creditors of Medpoint Management, which operates Arizona Nature’s Wellness dispensary in Phoenix, tried to force Medpoint into bankruptcy.

A federal judge dismissed the request because bankruptcy protections are not allowed when dealing with a substance that is illegal under federal law.

In another case, a dispensary in Gilbert was the subject of a long-running legal dispute between owners and developers that spilled over into Clifton and closed the dispensary there in 2014, the Eastern Arizona Courier reported.

The state should have used a merit-based system to avoid choosing people who had never run a legal business and “didn’t have a track record of writing things down,” said Ryan Hurley, a Scottsdale-based attorney who specializes in the medical-marijuana industry.

Newly minted dispensary owners weren’t filing corporate documents or contracts and often didn’t hire accountants, Hurley said.

Tucson dispensary owner Puchi-Saavedra lauded the state for issuing licenses randomly and giving everyone “the same chance of winning.”

“Either way, there were going to be lawsuits. The demand to get into this business was so high,” she said.

Jeff Kaufman, a Scottsdale-based lawyer who represents a variety of players in the industry, said the lottery is “perfectly fair.”

If Arizona used a merit-based system, “a lot of friends and relatives of people involved in grading the applications would have the best scores,” Kaufman said.

Kaufman had a simple explanation for partners breaching contracts.

“It ultimately comes down to greed or lack of competence,” he said. “But mostly greed.”

In one common scenario, groups of applicants applied in multiple districts with the understanding they would share a license, Kaufman said. But those agreements would fall apart when one partner won a license and refused to acknowledge the other partners.

The “boardroom brawls” began as soon as the first dispensaries opened, said Will Humble, who ran the ADHS until March 2015.

Although a “loud group” of investors lobbied for a merit-based system, “I never even entertained that approach,” he said.

With a state agency “grading” business plans, “you are guaranteeing there will be endless litigation,” he said.

The ADHS tried to include objective standards, such as preference for applicants who had never filed for bankruptcy or been behind on child support or back taxes, Humble said.

But a judge removed those standards except for the $150,000 requirement, which Humble said favored applicants who had “a better chance of success than a guy watching cartoons in his living room.”

A common request in the civil lawsuits, such as the Downtown Dispensary dispute, is for dispensaries to go into receivership and end up in the custody of a third party.

In Payson, a receiver — a person appointed by a judge to run the business while litigation unfolds — took charge of Uncle Herb’s dispensary after a bitter dispute between the owners over how funds were handled, the Payson Roundup reported in October.

Tom Salow, head of the medical-marijuana program at the ADHS, said he could not disclose how many dispensaries ended up in receivership, but it has happened “at least a handful of times.”

“We do see a lot of it going on,” Salow said of the business disputes, but much of the litigation doesn’t affect licensing, and the ADHS lacks the authority to intervene.

The ADHS can revoke a license, but state law prohibits officials from disclosing details, Salow said.

An ADHS-commissioned review of Arizona’s program said the agency has not revoked any dispensary licenses. One dispensary forfeited its license, the Jan. 22 report by Beacon Information Designs said.

For repeat offenders of agency rules, the ADHS calls “provider meetings” to agree on heightened scrutiny. So far, 10 to 15 percent of dispensary licensees have been called to these meetings, the report said.

As new medical-marijuana programs learn from other states’ experiences, disputes likely will lessen, said Taylor West, deputy director of the National Cannabis Industry Association.

“We are in a process of transition from a completely underground market to a sort of in-between market, to now in some states a fully legal market,” she said.

She expects future regulatory frameworks to require common business practices, such as written contracts and up-to-date record keeping.

Still, “anyone getting into this industry is kind of signing up for a bit of a roller coaster ride.”