Brian Garfield, author of “Death Wish,” “Hopscotch” and some 70 other books, died of complications from Parkinson’s disease Dec. 29 at his Los Angeles area home. He was 79.

Garfield grew up in Tucson and was profoundly influenced by the country and the lore of the West.

He wrote his first book, the pulp Western “Range Justice,” when he was just 18. He continued to churn out Westerns while he attended the University of Arizona, where he received both his bachelor’s (1959) and master’s degrees (1963).

His 1972 book, “Death Wish,” was inspired by an act of vandalism on his sports car, Garfield’s wife, Bina, recalls.

“He was at a party at the bottom of the George Washington Bridge,” she says. “He had an old convertible and the top had been slashed. It was raining and he got soaked going home. He was so pissed at getting soaking wet that he said, ‘If I ever find who did this, I’ll kill him.’ The whole idea of the book is what happens when you stay in that frame of mind.”

Garfield was catapulted to fame when “Death Wish,” the story of a mild-mannered architect who becomes a right-wing vigilante after his family is attacked, was made into a movie starring Charles Bronson.

The film missed the point, he often said. He was not happy about it, or any of its five sequels.

“The point of the novel ‘Death Wish’ is that vigilantism is an attractive fantasy, but it only makes things worse in reality,” he said in a 2008 interview. “By the end of the novel, the character (Paul) is gunning down unarmed teenagers because he doesn’t like their looks. The story is about an ordinary guy who descends into madness.”

Garfield was happier about the 1980 movie adapted from his Edgar Award-winning novel “Hopscotch,” which he wrote as an antidote to the violence in “Death Wish.” He penned the screenplay and co-produced the film, which starred Walter Matthau, Glenda Jackson and Sam Waterston.

Garfield’s books covered a wide spectrum — historical fiction, non-fiction, Westerns, mysteries and pure fiction. His “The Thousand-Mile War: World War II in Alaska and the Aleutians” was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in nonfiction. His non-fiction “The Meinertzhagen Mystery: The Life and Legend of a Colossal Fraud” was deeply researched and revealed new things about the man who conned Winston Churchill and others.

More than 20 million copies of his books have been printed and translated into several languages. Nineteen have been adapted into films, and several more are in development, said his literary agent, Judy Cottage.

He was never interested in being pigeon-holed into a genre.

“Each book is like a different course in school,” his wife has quoted him as saying. “I really don’t want to take the same course again and again. If the writer gets bored, heaven help the reader.”

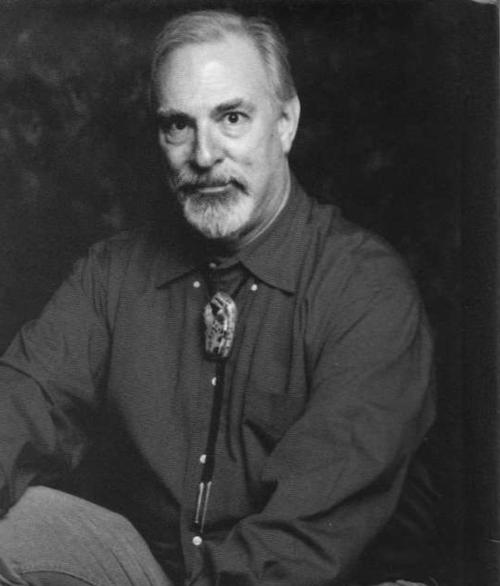

Garfield was an impressive personality to those who knew him. Often sporting an ascot or a bola tie, he had a quick wit, a hearty laugh and spun spellbinding stories for his friends.

Former Tucsonan Nancy Wolter knew Garfield for more than 50 years.

“His accomplishments never diminished, but his personality was what riveted one’s attention,” she said. “Witty, honest, kind, yes, but a world-class raconteur, making you feel as if you were there when Glenda Jackson said ‘yes’ to starring in ‘Hopscotch,’ or what it was like to research that incorrigible man Richard Meinertzhagen.”

Garfield was born in New York City and moved to Tucson with his mother, the late artist Francis O’Brien, when he was 7.

He attended the Southern Arizona School for Boys and fell in love with horses and the West, which led to his Western novels, a genre he stuck to early in his career.

He loved writing, but at one point he toyed with the idea of being a rock ‘n’ roll star. In the late 1950s, his band, the Casuals — later called the Palisades — was hot in Tucson. Eventually they had a top-40 hit, “I Can’t Quit,” appeared on “American Bandstand” and toured the East Coast. But that tour was during the winter, and the national recognition they hoped for never came.

It wasn’t long before the members decided rock ‘n’ roll wasn’t their calling. Becoming famous really wasn’t what they were after anyway, Garfield said when the band got together for a reunion in 1992. “I think we were all just anxious to postpone what we had to do,” he said.

Garfield was fiercely interested in the environment and through the Garfield Foundation gave generously to projects that tackled such issues as global warming and biodiversity conservation. He was also a supporter of the UA and donated a number of his mother’s works — Francis O’Brien was a protégé of Georgia O’Keefe and an accomplished artist — to the UA Museum of Art.

The 79-year-old Garfield is survived by his wife, Bina, and several cousins. Services are pending. In lieu of flowers, the family asks that donations be sent to one of his favorite charities, The Wildlife Waystation, an animal sanctuary in Sylmar, Calif. (wildlifewaystation.org)