Over the years, Bernandino Hernández has seen journalist friends killed. He has been threatened and harassed for his work, barely escaping his own death a few times.

In January, he was beaten by state police officers in Guerrero, Mexico, who he said also took his money, broke his cameras and took the memory cards, forcing him to leave the state — at least for a while.

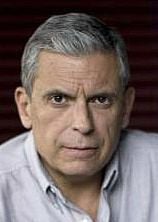

“Being a journalist in Mexico is like being a criminal. They go after you, you can get killed anywhere,” said the 48-year-old photojournalist. “You have to try to save your life, to hide to flee.”

Despite everything he can’t stop doing what he’s doing. “It’s something that I have inside me,” he said. “One person alone cannot change the world, but we can all do it together.”

Bernandino Hernández

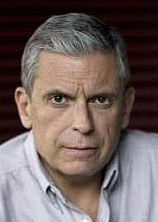

Enric Martí

Mort Rosenblum

Hernández, together with Enric Martí, an Associated Press regional photo editor based in Mexico City, will talk about the challenges in covering Mexican violence Tuesday at a panel sponsored by the University of Arizona’s Center for Border & Global Journalism and moderated by UA professor and co-director of the center Mort Rosenblum. They will also have an informal conversation Monday at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Tucson.

Mexico has become one of the most dangerous countries for journalists in the world. On average, a journalist was killed every month last year, freedom of the press advocates reported.

From 2000 to January of this year, Article 19, a group that monitors violence against journalists worldwide, has documented the murders of 114 Mexican journalists targeted for their work, usually in relation to their reporting on crime, corruption and politics in cartel-dominated states.

The violence against journalists goes hand in hand with the broader crime trends Mexico is facing amidst increasing cartel infighting and corruption. In 2017, a record of more than 25,000 murders was recorded across the country, Reuters reported.

Through his work, Hernandez tries to show the reality, he said. Some of his photos are graphic, he said, but he wants youths to see how their lives could end based on the decisions they make, “how we are killing each other off.”

Hernández started earning a living selling coconut oil on the beaches of Acapulco, Guerrero. As an 11-year-old orphan, he taught himself photography and started to cover protests and poverty for a local newspaper when he was 14 or 15.

Eventually, as crime escalated, his photographs began to document that violence. It is now said that he often reaches crime scenes before the police.

But in order to be able to photograph so much violence, he said, “you have to do it with your heart in your hand.” Photographing young children and women who have fallen victim to this wave of crime hurts him the most.

Bloodstained clothes hang on a fence outside a restaurant after gunmen entered and opened fire, killing two and injuring several others along Acapulco’s main beachside avenue. The clothes were left hanging by forensic workers but were not taken for the investigation.

He avoids showing the faces of children and has put his camera down when a grieving family asked him to.

Since UA professors Celeste González de Bustamante and Jeannine Relly started researching violence against journalists in 2011, they’ve seen it shift across different states in Mexico, depending on what the state is doing to combat organized crime.

“The real tragedy,” González de Bustamante said, “is that it has continued despite the fact that Mexico has a very strong law since 2012 to try to help protect journalists and human-rights workers.”

Most cases go unsolved.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists’ 2017 global impunity index, Mexico ranks sixth, under countries such as Syria, Somalia and the Philippines. The group has called it an epidemic that allows criminal gangs, corrupt officials and cartels to silence their critics.

The aggressions have also led to changes in how journalists do their work, said González de Bustamante, whose research has included interviews with more than 100 journalists and press freedom advocates along both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border.

Journalists try to work together when they go to crime scenes to protect themselves; outlets don’t publish their bylines with certain stories, and there are cases of self-censorship, she said.

Journalists in Mexico are vulnerable not because they are in the crossfire, but due to the stories they write, Martí said.

“When you are at war, there are generally two sides trying to in some way gain the media,” he said. “But in a place like Mexico, especially when it comes to the cartels, they don’t care about anything else but to ensure the media does what (the cartels) want, the same way they want politicians to do what they want.”

And with no clear sides, it’s very difficult to know where the threats are coming from, Martí said, whether it’s from the cartels, the government or the military.

He has a lot of admiration for the journalists who cover and document what’s happening in their countries, those who don’t have the benefit of returning to the comfort of their homes after they cover the story, he said. Martí worked in Nicaragua during the 1980s and then moved to Sarajevo, where he joined AP. He was also AP Middle East photo editor in Jerusalem and Cairo during tumultuous years before moving to Mexico.

Martí brought Hernández’s work to the annual Bayeux-Calvados War Correspondents Awards in France last year, where Rosenblum was a judge and says he was frozen by the images on display.

“I have seen a lot of violence and mayhem, pretty ugly stuff in a half century of reporting, but it was something about the way he is able to show the impact of the cruelty and callousness of this kind of drug crime violence going on but also the humanity of it somehow,” Rosenblum said.

“When we hear about street violence in Mexico or in Acapulco or elsewhere, we hear shocking figures but it doesn’t penetrate you,” said Rosenblum, who also worked with Martí in Bosnia and the Middle East and is a former AP special correspondent and bureau chief in Africa, Southeast Asia, Argentina and France.

“We have defenses that push it away. We hear certain words that make you kind of tune out. But you cannot miss Berna’s pictures,” he said. “His pictures bring it to you, put you into it, and you get a sense of what this noble neighbor of ours is now facing for whatever reason.”

For his part, Hernández said he will continue to do what he does best, for as long as he can.

“I’ve said I’m married to death. We go hand in hand. We bathe together, we sleep together, we are on the street together. As long as I hold her hand I’ll be here,” he said. “The day I let go, maybe I’ll go, too.”