Sheree García grabs her cloth mask and drives across town. When she gets to her students’ homes, she lowers the back of her truck so they can grab a home-built computer and a goodie bag.

The Wright Elementary School teacher packed up coloring books, crayons, mini workbooks from the dollar store and Smarties candy.

While Tucson’s largest school district, Tucson Unified, has worked to supply portable devices for all of its families in need, Chromebooks for García’s students didn’t arrive until the sixth week of school closures. And García just couldn’t wait that long.

Like teachers across Tucson, García takes it upon herself to use personal connections and her own money to ensure her students have necessities, from computers for remote learning to food in their cupboards.

Amid the coronavirus shutdowns, Tucson educators have created a grassroots support system to supply families in need with essentials.

ALL IN A DAY’S WORK

Starting at 7:15 a.m., García can be found online, tutoring students. She teaches classes over Zoom, helps families deal with computer issues, and checks in to make sure students are fed and have a quiet place to do schoolwork.

Because TUSD limited devices to two per household and because some families were unable to pick up computers when they were distributed, García continues to pick up home-built computers from her tech-savvy friends. She’s also purchased webcams and microphones.

After she’s made arrangements with families, she makes the drive to the midtown neighborhood and the children whom she used to see every day.

At 4 p.m., García heads to a seven-hour shift at Walmart. And when she gets home, at 11 or midnight, she takes calls from parents trying to prepare for the next day.

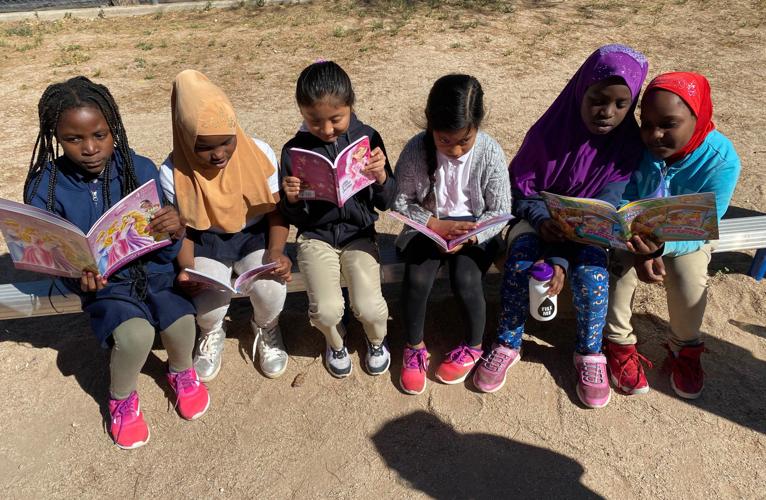

The English language development teacher has many low-income and refugee children in her combined second- and third-grade classroom. When she started remote learning in March, none of her kids were able to get onto the online classes. Now, all 22 have access.

When TUSD passed out Chromebooks and tablets at her school two weeks ago, García was there. She knows her families’ needs and she is relentless.

“I’ve been teaching 37 years, and I don’t give up,” she says. “I was calling my parents to get their little bottoms over there. I said, ‘I’m here. Come right now. I’m waiting for you.’”

With masks and gloves, educators at Wright called their families. And along with computers, books, school supplies and playing cards, they handed out bags of fruit, vegetables and bread from the community food bank.

And on Fridays, they put together bags of food to get families through the weekend.

ABOVE AND BEYOND

Before the coronavirus hit, Wright Elementary and other schools across the Tucson-area were already providing students and families with services that go beyond a child’s education. The pandemic has only increased the need.

At Holladay Magnet Elementary on Tucson’s south side, families have become accustomed to taking food boxes home for the weekend — an effort that’s been stepped up since the campus closed. Then there’s the school pantry, with necessities like diapers, toilet paper and food, supplied by donations from teachers and staff, local churches, nonprofits and community food banks.

"We're tough as saguaros," editorial cartoonist David Fitzsimmons says. He says he saw a video made for the people of Detroit and became inspired to do his own take for Tucson.

“We’re extremely resourceful,” says Holladay principal Tonya Strozier. “If I have to give money, I’m going to give money. If I have to buy it, I’m gonna buy it because these are my kids.”

So when it came time for families to pick up workbooks, it’s no surprise that Holladay Elementary kindergarten teacher Jennifer Lee made supply deliveries to all her families, as did other teachers.

Many families at the high-poverty school lack transportation, and some kids are home alone or caring for younger siblings while parents with essential jobs go to work.

It’s not the safest neighborhood for them to walk to the school by themselves, Lee says.

At one house, the mother told Lee that they didn’t have internet and were running out of food.

“I just couldn’t hear it,” Lee says.

She went to the store and came back with three boxes of food — pasta, soups, dried goods, bags of oranges, a couple of gallons of milk. Whatever would go the farthest and feed the most kids.

Lee pooled money with other teachers at her school to bring food to another mother who lost her job.

“We really are trying to do what we can to cover all of our families, and it’s not just our students but the families themselves,” Lee says.

The school’s truancy team has been turned into a triage unit. If a family needs food or other necessities, including covering an electric or water bill, they run to find a solution for them — not tomorrow, but now, Strozier says.

“We’re gonna stick together in this thing,” she says. “We need each other. I’m not necessarily interested in the two-plus-two. I wanted to know where these kids are. Relationships matter more than anything else right now.”

Strozier also made sure her families had an internet connection. Although companies are offering reduced-cost internet because of the pandemic, it’s still not accessible to some families, for example, if they had their internet cut off because they couldn’t pay.

So Strozier ordered hotspots using federal Title 1 funds designated for schools serving high populations of low-income families.

“I don’t feel like internet access should be a privilege,” she says. “In this situation, equity is a real barrier, so that’s why we’re just doing whatever we need to do.”

RISING TO THE OCCASION

Isabella Romeo, a fourth-grade teacher at Holladay, has spent hours on the phone with parents helping them get online and troubleshooting technology problems. Hardly a tech expert, Romeo has taken on this role because she has to — there is no one else to do it.

Romeo also bought and delivered food to families, some in hardship from the loss of a job or reduced hours due to COVID-19.

She’s on a text thread with her principal and about 20 other educators at the school, constantly communicating about students and needs that arise.

“You just see who needs what and then the teachers rise to the occasion and get whatever the student needs,” Romeo says.

Earlier this week, García continued to bring computers to her families at Wright. She’s still waiting on her stimulus check, and when she gets it, she’ll give her tech-savvy friends some money.

On a recent night García had off from her Walmart job, she created care packages for her students, all moving on to another class next school year. She packed up Play-Doh, toy cars, Smarties and letters telling them how much she misses them and appreciates their efforts with remote learning.

“I do a lot for my kids,” she says. “I always buy them little prizes and motivators. You know how teachers spend their own money. We can’t help it.”

Photos: Graduating seniors at Amphitheater HS get a personal greeting

Amphi HS students, graduation greeting

Updated

Amphitheater High School student body present and graduating senior Emily Mejia Lopez accepts a senior graduation sign from principal Jon Lansa at the Lopez home near Prince Road and Stone Ave. in Tucson on May 1, 2020.

Amphi HS students, graduation greeting

Updated

Isaac-John Onwuamaegbu and salutatorian of the graduating senior class at Amphitheater High School, is greeted by principal Jon Lansa in Tucson on May 1, 2020. Onwuamaegbu will speak during a video ceremony.

Amphi HS students, graduation greeting

Updated

A happy Augstin Willem, a graduating senior at Amphitheater High School, is greeted by principal Jon Lansa near Oracle Road and Stone Ave. in Tucson on May 1, 2020.

Amphi HS students, graduation greeting

Updated

Ralph Acosta, valedictorian of the Amphitheater High School senior class, is greeted at his home near 22nd Street and 12th Avenue by principal Jon Lansa in Tucson on May 1, 2020. Acosta will speak during Amphi's video graduation ceremony.

Amphi HS students, graduation greeting

Updated

Amphitheater High School Principal Jon Lansa knocks on a door seeking a graduating senior student in an apartment near Oracle Road and Glenn Street in Tucson on May 1, 2020. She was at work, so he left the sign with a relative.