Since the Bighorn Fire started one month ago today, the Tucson Wildlife Center has treated only one animal injured by the blaze: a fledgling barn owl with singed feathers on its head.

But Lisa Bates, the center’s co-founder and executive director, worries that the lack of patients may not reflect the fire’s true toll on the creatures that call the Catalinas home.

Despite some hopeful signs of animals escaping the flames, Bates said the hard truth is that wildfires do kill wildlife, and there isn’t always much firefighters, game officials or even animal rescue groups can do about it.

“It’s a hard thing working a fire, trying to help the wildlife,” Bates said.

"We're tough as saguaros," editorial cartoonist David Fitzsimmons says. He says he saw a video made for the people of Detroit and became inspired to do his own take for Tucson.

What’s happening now reminds her of the Aspen Fire, which burned for about a month in the summer of 2003, scorching almost 85,000 acres and destroying more than 300 homes and businesses in Summerhaven.

During that fire, Bates and her wildlife rescue crew were able to help only a handful of animals, including a fox and a coyote pup they brought back to the rehabilitation center and a few deer they supplied with food and water near the fire line.

Ample evidence of animals escaping

Bates said they saw many more animals — some with burned feet or fur pockmarked by embers and hot ash — that couldn’t be rescued because they couldn’t be caught.

“We were only able to help a couple of animals up there,” she said. “There was bound to be more.”

As of Friday, the Bighorn Fire had scorched close to 120,000 acres, making it the largest fire on record in the Catalina Mountains, according to Coronado National Forest spokeswoman Heidi Schewel.

And yet Bates said she hasn’t fielded any calls for assistance from the U.S. Forest Service, the Arizona Game and Fish Department or anyone else working the fire. “We had hoped they would call us if there were any injured animals,” she said.

Game and Fish spokesman Mark Hart has a simple explanation for that: He said the rescue groups haven’t been contacted because there still haven’t been any reports of animals hurt or killed by the fire.

“Surely there have been some,” he said, “but we would expect losses to be minimal, except in a case of a mishap” like animals getting trapped in a box canyon or surrounded by fast-moving flames.

“These animals have been living with fire for centuries,” Hart said. “In most instances, wildlife knows how to get out of the way of wildfire.”

Game officials have seen ample evidence of that over the past month.

In the early days of the Bighorn Fire, when the blaze was burning along Pusch Ridge and into Catalina State Park, mule deer were spotted making a rare, mid-day trek westward across Oracle Road on a wildlife bridge built to protect them from traffic, if not wildfires.

More recently, Hart said, there have been reports — and photos — of black bears in places they aren’t commonly seen, namely low down in Catalina State Park and off the Catalina Highway in the Seven Cataracts area below Windy Point.

Habitat impacts might not be seen right away

Then there is the mountain range’s newest and most famous wildlife population: the bighorn sheep that were reintroduced there in 2013.

Based on field observations and photos and videos submitted by Foothills residents, Hart said the sheep seem to have dispersed below the burned area between Pusch Ridge and Ventana Canyon.

In a few cases, the animals have been hanging around near homes high up in the Foothills.

Hart said the sheep will likely return to higher ground once the flames are out and the loud, low-flying air tankers disappear.

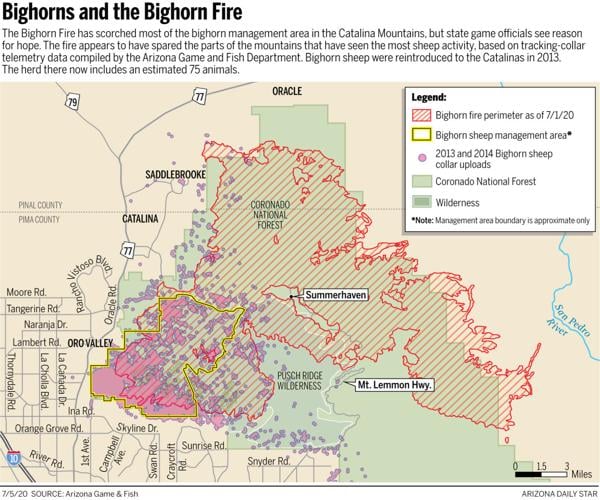

The fire has burned across most of the bighorn sheep management area, but it appears to have spared some of the sheep’s favorite spots, based on tracking-collar telemetry data collected by game officials since the animals were reintroduced to the Catalinas.

Hart said the herd now includes an estimated 75 animals, including several lambs that have been spotted since the Bighorn Fire broke out on June 5.

Wildlife officials have also recorded a few early signs of the post-fire recovery to come, including a Gould’s turkey foraging for food in a burned area near the old back road to the top of Mount Lemmon. “It was good to see wildlife in the black,” Hart said.

He said state game officials plan to get a firsthand assessment of the fire damage “when it’s safe to do so.”

Some impacts might not be seen right away.

The Monument Fire burned more than 29,000 acres in the Huachuca Mountains in 2011, but Hart said officials didn’t know the true extent of the habitat loss until the following year, when hungry bears suddenly started showing up in nearby Sierra Vista in search of food.

Unlucky owl almost ready to take flight

Something similar could happen after the Bighorn Fire, depending on how intensely it burned in certain areas.

“There’s still a lot we don’t know, obviously,” Hart said.

So far, though, the creatures of the Catalinas seem to have escaped the worst of it. “Based on our limited observations, they’re getting out of the way of the fire,” Hart said.

All but that one unlucky barn owl.

Bates said the roughly 3-month-old bird was brought to the Tucson Wildlife Center at the east end of Speedway on June 17, after someone found it sitting on the ground disoriented in the Golder Ranch area.

The owl “smelled like wood smoke,” with blackened feathers around its head, she said. “It’s hard to say how (it) got burned.”

The owl has since recovered and could soon be released back into the wild. Bates said staff members are flight-testing him now and “getting him some exercise to make sure he’s ready to go back out.”

When the time is right, the owl will be returned to the same area where it was found.

“We’d prefer the fire to be out first,” Bates said.

Photos: In Tucson, face masks are for more than just people

Face masks on objects

Updated

A Jeep sports with eyes like those from the movie "Cars" sports a COVID19 mask outside Alpha Graphics near the corner of Tanque Verde and Kolb, Tucson, Ariz., July 3, 2020.

Face masks on objects

Updated

The large Tiki head at the entrance of The Hut, 305 N. 4th Ave., wears a mask in response to the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) in Tucson, Ariz., on April 5, 2020.

Face masks on objects

Updated

The noted bull testicles on the statue outside Casa Molina at Speedway and Wilmot, usually painted in various schemes and wild colors, are in these CONVID19 times now sporting a face mask, March 27, 2020, Tucson, Ariz.

Face masks on objects

Updated

A dinosaur statue over the doors of MATS Dojo at 5929 E. 22nd St., sports an athletic cup for a face mask in the second week of COVID-19 restrictions, March 31, 2020, Tucson, Ariz.

Face masks on objects

Updated

The venerable T-Rex outside the McDonald's at Grant and Tanque Verde comes around late, but strong, to the mask game, May 13, 2020, Tucson, Ariz.

Face masks on objects

Updated

The iconic Casa Molina bull and matador statue both sported masks on the first full week of the loosening of COVID-19 restrictions in mid-May.

Face masks on objects

Updated

Father Kino's horse practice safe social interaction by wearing a mask even if Father Kino himself isn't. The statue sits at Cherry Fields at 15th Street and Kino Boulevard, Saturday, May 2, 2020, Tucson, Ariz.