PHOENIX — Arizonans have no legal right to know where the state obtains drugs to execute inmates, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled Tuesday.

But the judges said people do have the right, through official witnesses, to hear what is happening in the death chamber to better monitor how the state puts people to death.

The judges acknowledged claims by attorneys for both prisoners on death row and the First Amendment Coalition that knowing who made the drugs and things like the expiration dates would help the public better monitor whether the state is acting constitutionally in how it puts people to death.

Judge Paul Watford, writing the majority ruling, said this information is not part of any official record of the execution proceeding, material to which the public is entitled.

“It is simply information in the government’s possession that would enhance understanding of executions,” he wrote. That, however, does not grant a public right of access.

Dale Baich, the federal public defender for Arizona, said the problem is that state officials have been less than transparent — and less than truthful — in obtaining execution drugs in the past.

For example, he said the Department of Corrections claimed it had obtained lethal drugs legally in 2010 and 2011.

“We now know as a result of litigation and other disclosures that the state wasn’t being forthright,” said Baich, whose office handles most death penalty appeals in the state.

In 2015, the state tried to import sodium thiopental from India despite the fact that there was a federal injunction in place prohibiting that action. That resulted in the U.S. Food and Drug Administration seizing a $27,000 shipment ordered by the state at Sky Harbor Airport.

It isn’t just Baich who has concluded that the state has been less than honest.

Appellate Judge Marsha Berzon, writing separately, cited the botched 2014 execution of Joseph Wood.

She said state officials said that “nearly every detail” of its execution protocol had been made public. Yet the state administered 13 more doses of lethal drugs than the protocol authorized. And it took Wood two hours to die.

“These deviations in protocol are not isolated,” Berzon wrote. “In other executions, Arizona has obtained its legal drugs illegally or administered them in unauthorized dosages.”

For the moment, the question of execution protocols, including information on the drugs used and audio access, remains an academic question.

Arizona halted executions in 2014 after the botched Wood execution.

The moratorium, including one issued by a federal judge, has since been lifted. But any drugs the state had on hand have since expired.

Meanwhile, the state agreed as part of the lawsuit not to use midazolam, one of the drugs used to put Wood to death, as part of any future execution.

More to the point, manufacturers of various other medications that legally can be used in executions have refused to sell them to the state to be used for lethal injections. That leaves 14 people on death row who have exhausted all their appeals.

In July, Attorney General Mark Brnovich sent a letter to Gov. Doug Ducey, offering his help in the governor ordering a new supply of lethal drugs.

Ducey told Capitol Media Services at the time he was studying the letter and remains a believer in capital punishment. But, to date, Ducey has yet to respond, and the state still has no drugs that can be used for an execution.

“This is a very serious and complex issue,” gubernatorial press aide Patrick Ptak said Tuesday, adding he has nothing new to report.

Brnovich, for his part, is not letting up on the pressure.

On Tuesday, he said the 9th Circuit ruling came on the 35th anniversary of the murder of Vicki Lynne Hoskinson, a 7-year-old Tucson girl who disappeared while riding her pink bicycle at De Anza Park.

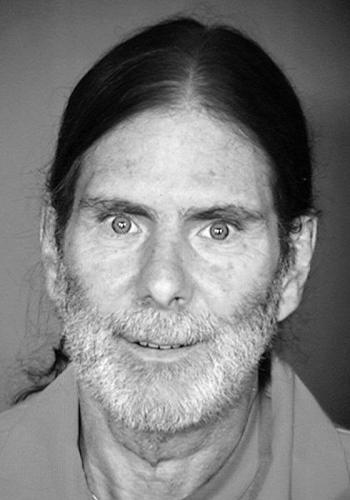

Police eventually arrested Frank Jarvis Atwood who had been released on parole in California in 1984 after serving his second prison term for sex acts with children. He initially was charged with kidnapping, with murder charges added after Vicki’s skull and some bones were found in the desert northwest of Tucson the following year.

“Now is the time to resume executions in Arizona,” Brnovich said Tuesday.

“Justice must be done for the victims of these heinous crimes,” he continued. “Their families have waited long enough.”

It isn’t just Brnovich pressuring Ducey.

In a letter to the governor obtained by Capitol Media Services, George and Debbie Carlson, Vicki’s parents, asked him to order pentobarbital to resume executions of inmates. They noted that Brnovich has said the federal government apparently is able to get the drug, making him believe so could Ducey — if he pursues the matter.

“We have come to a point of questioning where the rights of the victims come into the criminal justice system,” the couple wrote to the governor urging him to order the drug. “We are proof it does not!”

While refusing to require the state to provide more information on what drugs it eventually hopes to use for executions, the judges reached a different conclusion on the legal question of whether the right to witness executions also includes the right to hear the sounds the inmate is making as he or she is being put to death.

“The public has a First Amendment right to view executions in their entirety,” Watford wrote. He said the current practice of the Department of Corrections to put inmates to death behind sound-proof glass does not meet that requirement.

That issue of sound has become an issue since the botched 2014 execution of Wood.

Witnesses said while there was evidence of choking and coughing — and that it took 13 more doses of lethal drugs than the Department of Corrections protocols authorized — they could not hear anything other than the few moments when the microphone in the death chamber was turned on so the execution team could provide updates.

“Lifting Arizona’s restriction on the witnesses’ ability to hear would ensure more comprehensive coverage of executions in the state,” Watford wrote.

The judge said that conclusion was really setting no new precedent.

“Executions have historically been open to the press and the general public,” he said, going back to the days of public hangings.

“The crowds that gathered to watch those executions could, no doubt, hear the sounds of the entire execution process, even if not with perfect clarity.”