PHOENIX — Four key issues remain unsettled as negotiators for a Colorado River drought-adaptation plan wrap up discussions and prepare to send a complex package of water-saving proposals to the Arizona Legislature.

Farmers, developers and officials of the $4 billion Central Arizona Project said Tuesday they still aren’t satisfied with various provisions in a proposed drought contingency plan aimed at propping up imperiled Lake Mead. Because of that, negotiations over details will probably have to continue even when the Legislature starts debating the plan next week.

But leaders of the prolonged effort to produce a drought contingency plan for Arizona say they’re optimistic of getting the issues resolved and a legislative sign-off in time to meet a federally imposed Jan. 31 deadline to adopt the plan.

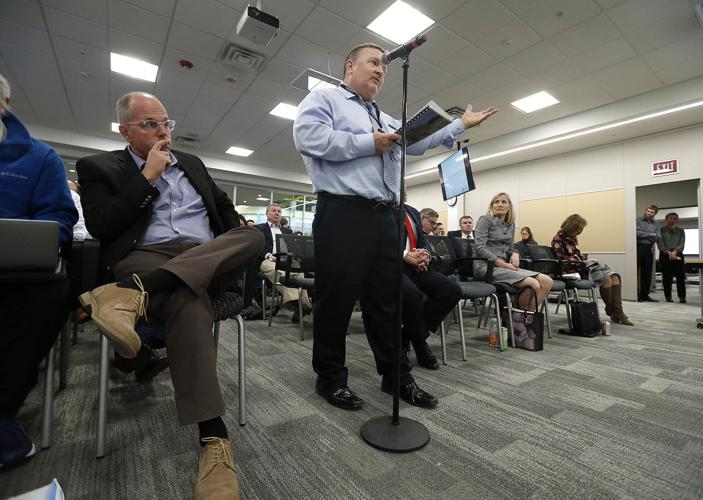

Tuesday, during the eighth meeting of an advisory committee working on the plan, members groped for solutions and compromises but those remained elusive, although progress was made.

“There are only four issues left. We have 82 things that we’ve solved,” CAP general manager Ted Cooke said at a news briefing after the meeting of the 40-member advisory committee that’s worked since July on the drought plan.

“It’s clear there’s some disagreements. If we demonstrated anything today, it’s that we have found a lot of compromise on a lot of issues,” said Hunter Moore, natural resources adviser to Gov. Doug Ducey. “If we continue to follow that pattern, I do” think the plan can be resolved, Moore said.

The committee, representing numerous big water interest groups, including farmers, developers, cities, tribes and home builders, is discussing a plan to save up to 700,000 acre-feet of river water over a seven-year period.

The hope is that the savings will prop up Lake Mead before it quickly falls to levels requiring catastrophic cuts in water deliveries to Arizona, California and Nevada in the Lower Colorado River Basin.

Federal Reclamation Commissioner Brenda Burman has warned she’ll impose her own drought-saving plan on Arizona and the other six Colorado River Basin states if the states don’t approve plans by Jan 31. Arizona and California are the only states without approved plans.

The Arizona Department of Water Resources and the governing board for the CAP — the state’s two biggest water agencies — have endorsed the plan’s current version, as has Ducey.

As the plan stands, Pinal County farmers would lose a big chunk of their CAP water once the first Colorado River shortage is declared, which could come as soon as next year. By 2023, the farmers must replace CAP supplies with groundwater — their only water source until CAP went online there in 1986.

The Tohono O’Odham Nation and the Gila River Indian Community and numerous Phoenix-area cities will have their supplies whittled down over time starting the same year. All these users would get their cuts “mitigated” by the use of outside supplies for a few years.

But at Tuesday’s advisory committee meeting, these unsettled issues emerged:

- Pinal farmers are scheduled to get 105,000 acre-feet of CAP water in both 2020 and 2021 if shortages are declared for 2020, less than half what they get now. In 2022, that supply will be whittled to 70,000 acre-feet a year if the river is running low due to dry weather.

Farmers, however, want 105,000 acre-feet of CAP water for 2022 as well, and it’s uncertain where that extra water would come from.

Tim Thomure, a committee member and Tucson Water’s director, said he would be prepared to offer 35,000 acre-feet annually for two years, water that would be placed on Pinal County farm fields.

But making that offer will require four changes in state law to make it easier for the city of Tucson to use or sell “credits” it would gain from storing the water on those fields to allow it to pump additional groundwater elsewhere, he said. State Water Resources Director Tom Buschatzke praised Thomure’s proposals as “creative,” but said some other interests whom he didn’t name might not support more water for farmers out of concern that it wouldn’t be fair to other water users.

- Paul Orme, lobbyist for four irrigation districts, wants more “certainty” about getting federal funding to help pay for the farms’ new groundwater wells, whose expected cost has escalated from $30 million to $50 million. The state and CAP have agreed to pay or support future legislation to provide close to half those costs. But Orme noted that competition for the federal funds with farmers in other states will be fierce, although Bureau of Reclamation officials in Arizona will support the Pinal farmers’ quest.

- The Central and Southern Arizona Home Builders Associations want 7,000 acre-feet of “mitigation” CAP water set aside to serve future suburban development, although officials say there is no alternative source of water to fulfill that request. The Gila River Indian Community has already agreed to lease 33,000 acre-feet of its CAP water for future suburban growth — once it’s certain that the drought plan will pass the Legislature.

The homebuilders groups say they want the extra 7,000 acre-feet included in the plan as a matter of “certainty,” and that pool of water could be removed once it’s clear the Gila Indian deal will go through. A Phoenix-based developer group, the Valley Partnership, disagrees, with its director Cheryl Lombard saying its members see no need for the extra 7,000 acre-feet.

- CAP and the Salt River Project utility are at odds over a plan for the utility to replace some water now stored in Lake Mead, which CAP wants to remove from the lake to help mitigate farm water losses. As the plan would work, the utility would supply CAP 50,000 acre-feet from 2021 to 2025. Cooke said his agency has legal, contractual and hydrological concerns with the idea.

He acknowledged that, currently, that issue is “the only one I don’t know how to (solve). But we’ll figure out a way to solve that.”