It was summer of 1999 when Vail School District Superintendent Calvin Baker boarded a bus to Phoenix with about 70 parents.

He had had enough. After busing hundreds of students out of Vail to attend high school in other districts for years, Vail applied for state funds to build its first high school, but a committee recommended to deny the request.

“We launched a little publicity campaign,” Baker says, his eyes gleaming. “A busload of parents — literally, we chartered a bus — and a caravan of cars went to the School Facilities Board in Phoenix, and the board unanimously reversed the decision of the subcommittee and approved funding.”

He recalls the effort to build Cienega High School as a moment that brought together a growing community. One of the superintendent’s proudest achievements is the connection the district has with that community today. Baker attributes much of Vail’s success to that community support.

On the cusp of wrapping up several decades of achievement, one word Baker uses to describe the Vail community is faithful.

Baker is retiring on Feb. 1 after 31½ years as Vail’s leader. He is also the senior member on the State Board of Education and says he’ll offer to finish out the school year in the position.

The longest-running superintendent of any single school district in the state, Baker has watched Vail grow from one school with 500 students to over 14,000 students in 22 schools. Come next school year, the new Mica Mountain High School, designed to serve 1,000 students with plans for expansion, is slated to open its doors.

When Baker took the lead in 1988, the district was riddled with controversy. Under his leadership, Vail has become one of the top performing districts in the state.

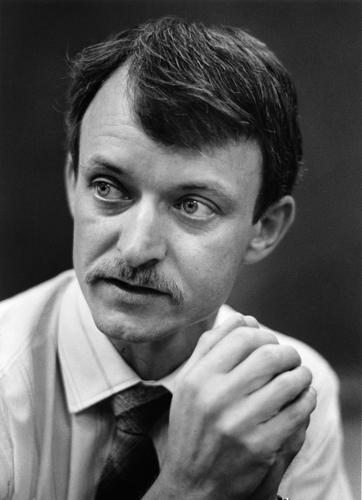

Led Vail School (now Old Vail Middle) in 1987

Baker remembers celebrating the win of funding being approved to build Cienega High. It was at Acacia Elementary’s courtyard, built with the intention of creating community space. The rural Vail locals and the newer residents who Baker calls “the new city folks” in Rita Ranch came together and forgot their differences.

“All these people from all these different backgrounds, they all gathered in the courtyard, and they were like all the fans of a winning state championship team,” Baker says. “They just loved each other. They were so proud of each other.”

As Vail first began to grow, Baker thought on what the district needed to retain. What made them truly great, he asked himself. His vision, which he’s instilled in Vail staff, students and families, is that education is a community effort — the district’s motto.

“The focus on serving parents and the focus on engaging the community — that built a rock-solid foundation for us to build from,” he says. “The most significant thing that I’ve done is simply hold the rudder steady.”

“A Moral center”

He’s held that rudder steady through a number of accomplishments and innovations. For example, in the ’90s as their enrollment exceeded capacity, Vail went on a year-round multitrack system for four years. Students were split into four groups with different school calendars, allowing the district to educate 800 students in a school built for 600.

In 2005, Vail opened Empire High, the first school in the country to completely replace textbooks with laptops. From that venture, the district created Beyond Textbooks, combining the district’s instructional methodology with an online delivery system, making it available to other districts.

Now there are more than 115 school systems, in every county in Arizona and in six other states, that use the program, some of which have become top-performing districts, Baker says.

Baker was always ahead of his time on changes in education and ways to impact student success, says former Flowing Wells Superintendent Nicholas Clement. He says opening a school that replaced textbooks with laptops was controversial when Empire opened.

“He took calculated risks,” Clement says. “He had the data, and his intuition said, ‘This is good for kids.’”

Baker was also on the forefront of understanding and investing in teacher training to impact students, Clement says.

John Pedicone, a former TUSD and Flowing Wells superintendent, got to know Baker when Vail was still a fledgling district of about 1,000 students, he says. Baker was one of the first to reach out to Pedicone when he became the Flowing Wells superintendent in the late ’90s.

Pedicone recalls testifying before the Legislature with Baker, years later, on behalf of additional funding for schools. Flowing Wells serves a lower-income population than Vail. Pedicone says Baker stood with him and appealed to the Legislature for equity and fairness.

“Real leadership comes when somebody has strong ethics and a moral center,” Pedicone says. “For any leader to be effective, that’s gotta be a key criteria. And with Cal, there was never a question about that.”

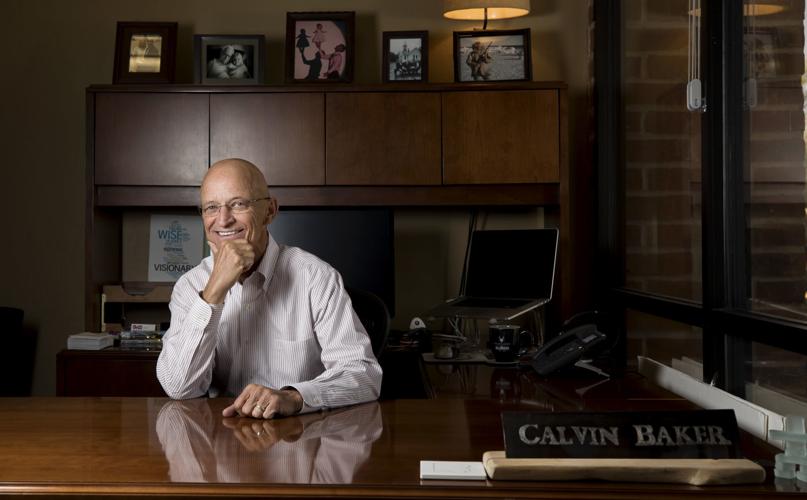

Calvin Baker, above, is described by former Flowing Wells Superintendent Nicholas Clement as a visionary “who took calculated risks,” such as replacing textbooks with laptops.

HOLDING STEADY

The Vail School District governing board chose John Carruth to be the next superintendent. Carruth started with Vail 24 years ago as a teacher. He held positions of assistant principal, director of special education and then assistant/associate superintendent for 15 years. A year ago, he left the district to become chief of staff to Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction Kathy Hoffman.

Baker says Carruth is the best choice to replace him: a skilled educator, authentic and deeply-rooted in the Vail community.

Carruth, a native Tucsonan, says he used to feel the weight of taking Baker’s place, but not anymore. Like Baker, Carruth sees the leadership role as a group effort, which he does with the support of the staff and community.

Like many in the district, Carruth talks about Baker like he’s a family member rather than a boss or colleague.

“I have been blessed to have him in my life, and I, like so many others in the Vail community, have benefited from that,” Carruth said. “He has largely been responsible for creating an environment by which the Vail School District and the Vail community could be successful.”

Behind Baker’s desk are framed photos — his wife in a thick winter coat, during the time he was a principal in Alaska, snow and ice behind her, hunting rifle in her hand. There’s a photo of his four sons, sitting on a bench before a tiny, old church on the Oregon coast. It’s his second son’s wedding day — the unrelenting romantic, Baker says.

His six children and 15 grandchildren are scattered across the country. Baker doesn’t know what life will be like without “eating, drinking and sleeping Vail School District,” he says.

Telling old stories at the conference table in his office, Baker struggles to quantify how much his leadership was responsible for the success of the district.

Earlier this year, Baker was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, which he described as an incurable but treatable form of cancer. With the district, as with cancer, he’s done what he could for a positive outcome.

When people hear he’s doing well with his diagnosis, they tell him it’s because of his strength. He exercises and eats the right food, but he has no control over the cell division that is or is not occurring inside his bone marrow, he says. He does what he can to hold the rudder steady, but so much in life — good and bad — is beyond his control.

In April 2018, Vail Superintendent Calvin Baker spoke to Cienega High School teachers, staff workers and students about demands for better pay and more school funding.

COMMUNITY-CENTERED

Baker grew up on a family farm in Minnesota. His parents, who both left school after eighth grade, taught him that education was the future.

He says he had very little appreciation at the time for the community that raised him. It wasn’t until later, building his own community that he looked back and recognized its importance.

“The focus of that community was raising their kids well,” he says. “Kids were not an inconvenience. They were not something that interfered with people’s careers. They were the focus.”

Baker’s family moved to Phoenix when he was in high school. He got his master’s at Arizona State University and taught in Phoenix for six years, before taking the principal job in Alaska. After nine years in a remote village above the Arctic Circle, he returned to Arizona, to be the principal of Vail’s sole school before becoming superintendent a year later.

Baker’s legacy is essentially what he saw as a child on his family farm — it’s a community that comes together for the common goal of raising children to the best of their ability. His legacy is Vail’s connection to the community, its service to parents and the high-quality staff, he says.

“I’ve worked really hard to be faithful to the district and the community, and people have been faithful to me,” he says. “It’s like a friendship or a marriage — you go through hard times. When everybody’s faithful, you can look back over the years — glad we were faithful ’cause now we reap the benefits.”

Calvin Baker, Vail School district superintendent, visits with eighth grade students in their science classroom in 2007.

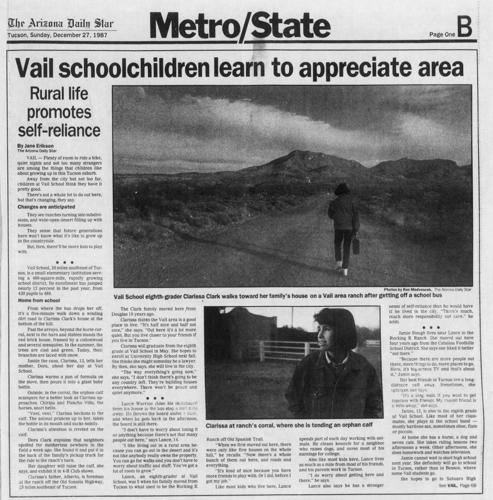

1987 story on Vail School, the only school in the Vail district.

1987 story on Vail School, the only school in the Vail district.