The Zika virus may come to Arizona, but — if the past predicts the future — it may not spread.

Arizona, particularly its warmer urban areas around Phoenix, Tucson and Yuma, grow healthy populations of the Aedes aegypti mosquito every summer. That tiny, ankle-biting mosquito can spread the viruses of yellow fever, dengue fever, Chikungunya — and now, Zika.

Arizona has had travel-related cases of dengue and Chikungunya, but those have not caused outbreaks here as they did in Mexico in recent years.

“Something,” probably a combination of lifestyle and climate, is keeping those diseases at bay, said epidemiologist Heidi Brown.

“Whatever was keeping them from transmitting dengue, whatever kept them from transmitting Chikungunya, is the same thing that is probably keeping them from transmitting Zika,” said Brown, of the University of Arizona’s Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health.

Brown is spending her research time these days “trying to tease apart” what those conditions are. And while she is reassured by “the science and the history” of Aedes-borne diseases in Arizona, she is reluctant to provide absolute assurance about the scariest aspects of Zika — its suspected ability to cause serious birth defects.

“I recently had a talk with a woman who is currently pregnant. My kid is only 2 years old, and it gives me a hugely different perspective on it. The science is telling us — and even the experience is telling us — the probability of Zika coming to Arizona is really very low.

“If I were a pregnant woman, I would try my best to be reassured by the science and the history, and then I’d do the kinds of things I can control around my house with respect to Aedes aegypti.”

Fight the bite!

Zika won’t appear in Arizona unless it is brought here by someone who travels to an area with outbreaks. That person would then have to be bitten by a mosquito and that mosquito would have to bite an uninfected person to begin the spread.

That’s why medical reporting is so critical, said Jessica Rigler, chief of the Bureau of Epidemiology and Disease Control at the state Department of Health Services.

State and county health officials will respond quickly to ensure that infected person’s environment is as mosquito-free as possible and that he or she is taking the proper precautions against being bitten.

Until that happens, Arizona health officials plan to fend off the Zika virus with surveillance and public education — basically, doctor’s reports, mosquito traps and slogans.

The traps won’t eliminate mosquitoes that carry the virus, but they will give health authorities a good map of where the mosquitoes are abundant.

The slogans — including the overarching “Fight the Bite! Day and Night” — are part of an education campaign that urges people to avoid bites by covering up, using repellent and policing their yards for breeding areas.

Those steps, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, are the most effective ways to prevent the virus’ spread.

If an outbreak does occur, other measures can be taken — spraying pesticides to kill adult mosquitoes, using larvicides in standing bodies of water, isolating hot zones where people are being infected.

Spread occurs when a mosquito bites a person with the virus and then bites an uninfected person, after the virus has had a chance to work its way from the mosquito’s gut to its salivary glands.

If you protect yourself from being bitten, you can neither contract nor spread the virus.

If you routinely police your yard for sources of water in which the mosquitoes might breed, you can make that task easier and your life more pleasant. The Aedes mosquitoes don’t fly far after hatching — as little as 50 to 100 feet on average. If you are being bitten, they are breeding at your house or a close neighbor’s.

mosquito found here

We won’t know ahead of time that Zika-infected mosquitoes are here, because vector-control officials don’t test for that. There is also no vaccine.

But mosquitoes that can carry the virus are here, even now at the end of winter, said David Ludwig of the Pima County Health Department.

Larger Culex mosquitoes, primarily Culex tarsalis and Culex quinquefasciatus, have been the primary targets of surveillance in Arizona over the past few decades.

They are vectors for the avian-borne West Nile virus, which is capable of killing a vulnerable adult or child, though most people have mild or no reaction to the virus.

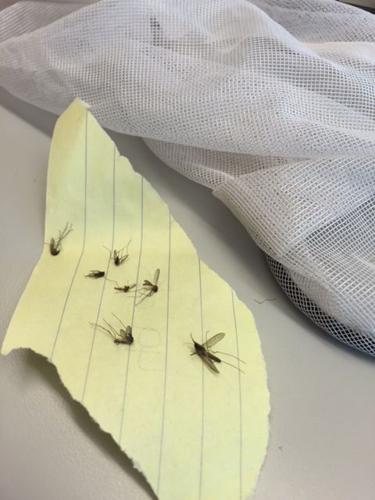

The smaller Aedes mosquitoes — those quick, pesky ankle-biters who feed all day long — were considered little more than a nuisance. But that attitude changed in recent years as outbreaks of dengue and Chikungunya occurred in Sonora.

Last week, the state of Sonora reported its first travel-related case of Zika, in an Hermosillo man who had recently visited Brazil, where Zika outbreaks are raging.

Health officials monitored the neighborhood around the man’s home for two weeks, but found no other cases.

So far, 193 cases of travel-related Zika have been confirmed by the CDC, with none in Arizona. The CDC says that number “will likely increase,” and warns that travel-related cases could cause local spread of the disease in areas where Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are endemic.

The CDC says states most at risk are Hawaii, Texas and Florida, where outbreaks of Aedes-borne diseases such as dengue and Chikungunya have occurred in the past, but all states with Aedes populations should be on alert, which isn’t easy since an estimated 80 percent of those infected with Zika show no symptoms.

Arizona is on alert, said Rigler of the state health department.

“We have rapid response teams and supplies in place here in Arizona ready to respond immediately to stop that possibility of outbreak,” she said.

In Pima County, the three vector-control specialists who monitor mosquito populations and respond to nuisance complaints have begun to deploy traps specifically designed for Aedes, in addition to continued monitoring of mosquitoes that carry West Nile virus, said Ludwig, of the Pima County Health Department.

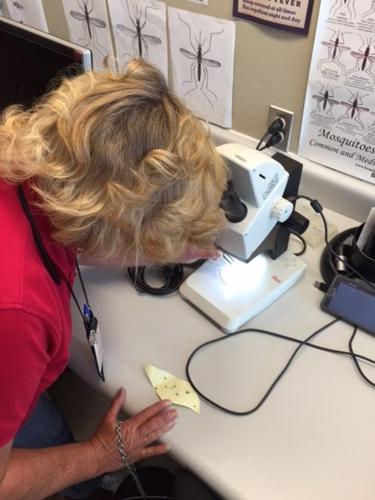

On a recent Thursday, vector-control specialist Cindy Bennett displayed results from a trap near a midtown storm sewer drain — a couple dozen mosquitoes, most of them appreciably smaller than the others. Under a microscope, she confirmed that the smaller ones were Aedes aegypti.

know your enemy

The state, along with county health departments and municipalities, started to monitor Aedes aegypti populations more closely after dengue outbreaks were reported in Mexico border cities in 2014.

“There has been a shift in attention, beginning in early 2015, for dengue. We purchased more traps and worked with local vector agents.”

Populations of mosquitoes are small this time of year. They bloom when the rains come in midsummer. For now, said epidemiologist Brown, the baseline population is being maintained by us.

Unlike the larger Culex species, which lay rafts of thousands of eggs in large bodies of stagnant water, the Aedes mosquitoes deposit eggs singly in backyard containers or clogged gutters, where they wait for dog bowls, abandoned tires and plant saucers to be refilled.

A communitywide effort to eliminate those breeding sources would go a long way toward insuring against an outbreak, said the health department’s Rigler.

“That’s really the best advice available and, if successful, we’ll never need to spread the alarm,” she said.

“The Aedes aegypti loves to live around people. It stays close to home, and if you’re vigilant and wearing insecticide and covering up, you won’t spread the disease.”