Scientists remain concerned about the potential for large meteors and comets striking the Earth with calamitous result, but a recent statistical study says the sun has already reduced some of them to rubble.

Researchers in Finland, France, the United States and Czech Republic used data on near-Earth objects gathered by the University of Arizona’s Catalina Sky Survey to discover a missing population of objects that apparently busted up long before they were expected to do so.

“Within 9 million miles of the sun, they just aren’t there and there should be some,” said Ed Beshore, who was principal investigator for the survey before leaving to help run NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission for the UA.

Some sort of gravitational or thermal force is busting them up, he said. “Now we need to explain it.”

Most of the objects that are close enough to the Earth to be potentially dangerous come from the Asteroid Belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter.

They venture closer to the sun and into Earth’s neighborhood when nudged from orbit by a variety of forces that include surface heating and cooling and the gravitational disturbance of large planets.

That’s when they are targeted by sky surveys looking to identify them and calculate their orbits. The Catalina Sky Survey, which currently employs two telescopes in the Santa Catalina Mountains in that search, has been at the task since 1998 and has discovered more NEOs than any other outfit.

For this recent study, an international team, led by Mikael Granvik of the University of Helsinki and including Beshore, used eight years of Catalina Sky Survey data to build a mathematical model of the NEO population by size and orbit.

That’s when they found the puzzling piece — the class of objects that came closest to the sun was missing 90 percent of its predicted population.

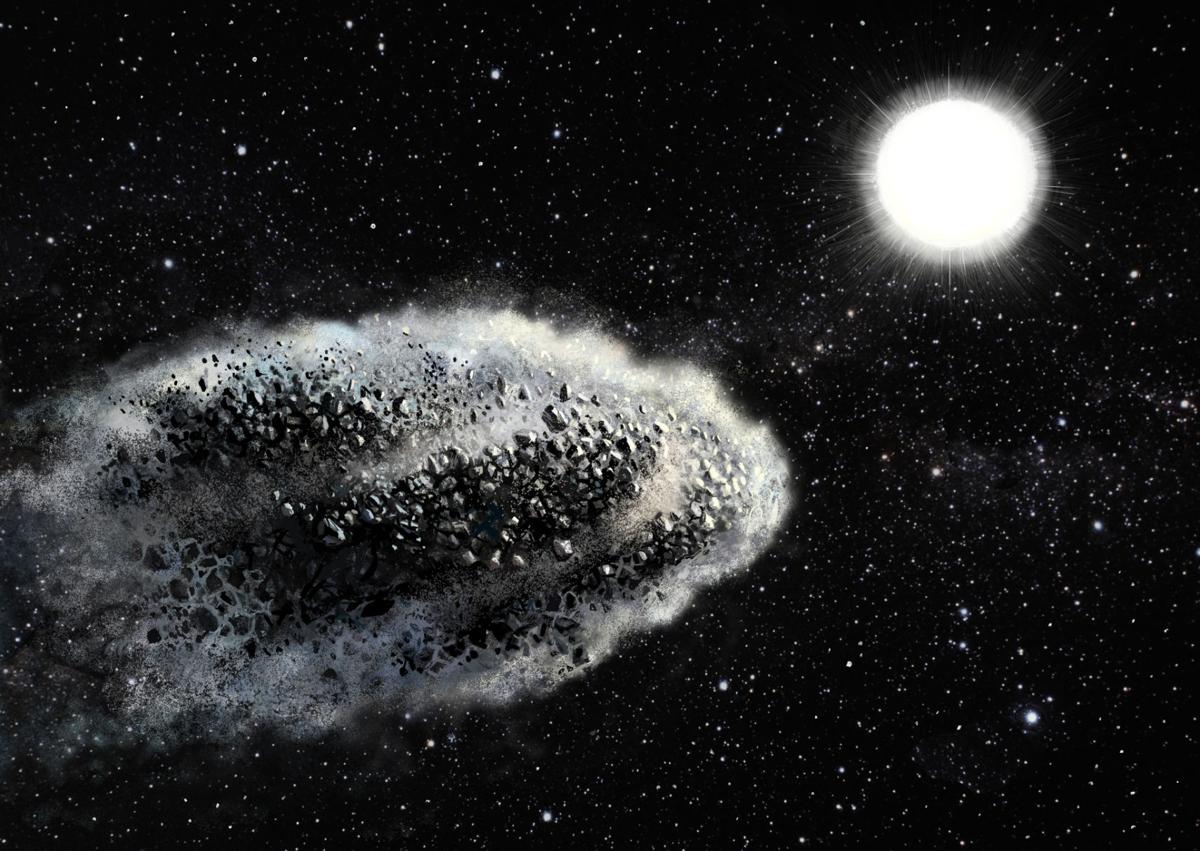

In a paper published in the journal Nature this week, researchers propose that asteroids and comets are breaking up far from the sun itself.

The theory explains how streams of asteroid material produced meteor showers when astronomers could find no “parent” objects for them, researchers from the University of Helsinki said in a news release.