COCHISE COUNTY — At times, their steep drop-offs resemble cliffs. They slash through two roads, making them impassable.

In some places, they’re so narrow you can step over them. Elsewhere, they’re so wide you couldn’t leap across them without falling into areas where you can’t see the bottom. Huge slabs of asphalt and soil have sagged into a couple of them, leaving behind open voids.

Three big fissures like this opened south of Willcox about a week ago. They join a parade of other fissure and road crack openings that happened during the intense monsoon. After the rains opened the latest fissures up, county officials closed sections of two roads and they haven’t reopened.

But while monsoons triggered the road closures, their ultimate cause was the collapse of ground underneath due to the area’s unregulated pumping for farming, said Joe Cook, an Arizona Geological Survey research geologist.

In places, the fissures run more than 10 feet wide and up to 16½ feet deep. They snake close to a half-mile into the neighboring high desert on either side of the roads.

Both closed roads are in areas of heavy farming and documented heavy land subsidence, in which the ground collapses after groundwater holding the soils together is pumped. Subsidence has opened nearly 45 miles of fissures in the Willcox Basin, Cook has said.

“The fissures are opened by rain. If you have continued subsidence, it keeps them active, and they’re able to swallow more sediment,” Cook said. “You wouldn’t have any damage to the roads if you didn’t have fissures there.”

In the past, these fissures had opened, then been covered up by road crews. But Cook said he expects fissuring to continue as long as groundwater pumping in the area continues to exceed the rate at which rainfall naturally replenishes the aquifer.

“There’s a clear cause and effect,” Cook said.

Water frustrations

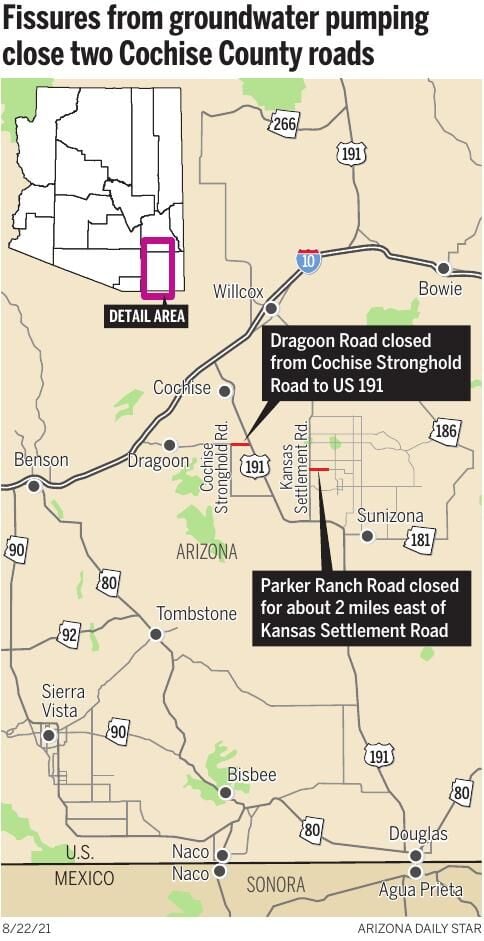

The fissures forced closures of sections of Dragoon Road in the Cochise area, and of Parker Ranch Road east of Kansas Settlement Road.

The Parker Ranch Road fissures are near the Coronado Dairy owned by the multistate dairy operator Riverview LLP, whose pumping to grow alfalfa and other feed crops has been a particular target for critics of the area’s agricultural base. But that fissure first opened when the dairy was under other ownership.

Both roads should be repaired this week. But a long-simmering debate over the pumping that triggered these road closures will continue once traffic is rolling there again.

The closures affect a 1-mile stretch of Dragoon Road east of Cochise Stronghold Road, pictured, and a 2-mile stretch of Parker Ranch Road.

A group calling itself Arizona Water Defenders has started a drive to gather petition signatures to force an election in November 2022 on whether to create strict groundwater management areas in the Willcox Basin and the Douglas Basin directly to its south. They need signatures from 10% of the registered voters in each basin for their proposals for a state-run Active Management Area to make the ballots.

The petition drive is fueled at frustrations with fissures, dried-up drinking wells and dust and noise from the land-clearing and pumping to supply the agriculture that represents 70% of the area’s economy. Their push is likely to draw strong opposition from farmers and their backers who wish to preserve the area’s longstanding tradition of private property rights.

A big question underlying this debate is: How much good will an Active Management Area do for a rural landscape when the other five such areas in Arizona exist to manage water use in Tucson, Phoenix and other urbanized settings?

Earlier fissures

The closures affect a 1-mile stretch of Dragoon Road east of Cochise Stronghold Road, and a 2-mile stretch of Parker Ranch Road. Five inches of rain fell in the Willcox Basin in the week before the fissures opened, making it impossible for Cochise County road crews to drive in and repair them last week.

One Parker Ranch Road fissure was still filled with water when a reporter visited it Thursday.

“The shoulders on Parker Ranch Road were so wet and saturated, we couldn’t get a dump truck in,” said Jackie Watkins, Cochise County’s engineering and natural resources director. “The fissure has water in it, and you get close to the edge of it, it’s 5- to 10-feet deep, that (truck) could slip into the fissure.”

In some places, fissures are so wide you couldn't leap across them without falling, like these ones around Parker Ranch Road.

Assuming no more rain falls by Monday, Dragoon Road can be reopened in two or three days and Parker Ranch Road can be reopened by week’s end, Watkins said.

These fissures opened almost six weeks after a 2½-mile stretch of U.S. Highway 191 was closed for a week after a storm left behind a huge crack south of Dragoon Road.

Unlike the more recent fissures, geologists were unable to determine if that crack was subsidence-driven, or formed naturally by repeated drying and wetting.

Also, at about the same time, part of a fissure that had opened repeatedly in the past two decades opened up once more at Dragoon and Cochise Stronghold roads, not far from where the latest fissure opened on Dragoon, and was filled in again. And on July 31, another storm opened up a fissure on Jefferson Road in the Elfrida area in the Douglas Basin. Not serious enough to require closing the road, that crack has since been repaired.

The latest fissures have caused major inconveniences for drivers, forcing them to go many miles out of their way.

On Dragoon Road, its eastbound lane was completely undermined, said geologist Cook, who visited both fissures last Monday.

Hairline cracks on both sides of the collapsed area extended across the entire roadway. On the north side the fissure extended into recently plowed land with a mix of long open reaches and zones of partial collapse and hairline cracks, Cook wrote in a blog post for the geological survey.

On Parker Ranch Road, the westernmost fissure has undermined the road’s eastbound lane. Asphalt slabs are sagging at that end, and the dirt underlying it gone, leaving behind a void.

When Cook was there Monday, “large chunks of the fissure wall periodically slumped into the water-filled fissure with loud splashes. At one point a large piece of asphalt in the road fell into the void below,” he wrote in his blog. “Although the total depth of the open portion of this fissure was not observable due to the muddy water, widths of at least 10 feet and depths of 13 feet were observed in drier portions to the south.”

At the easternmost Parker Ranch Road fissure, “the roadway was completely undermined with only a thin bridge of asphalt and soil bridging the gap formed by collapse along the fissure,” Cook wrote. “Broken and sagging asphalt was observed directly above the void with hairline cracks across the road on both sides of the collapsed zone.”

Cecil Harrington of Marana said his main access to the 220 acres he owns near Parker Ranch Road is a dirt road leading north from the road. From photos he saw of last week’s storms, that dirt road was “destroyed” by one of the fissures, Harrington said.

Some fissures snake close to a half-mile into the neighboring high desert on either side of the roads.

He’s repaired the road several times over the years because it’s not maintained by the county — most recently three months ago, he said.

“It was getting to where the rear wheels of my trailer would fall off in a fissure. I fixed it, so now it’s all destroyed again,” said Harrington, who visits his property five or six times a year to ride quads, camp and shoot guns. “Even worse, I can’t cross it at all now because of the fissure.”

Rocky and Tara Morrow live not far east of the Parker Ranch Road fissures. He’s a semi-retired rancher. She is a hospice caregiver and raises working Australian shepherd dogs.

Tara Morrow is frustrated that now, just to drive to Willcox, she must either drive north and then west on dirt roads to reach Kansas Settlement Road or drive south to the Sunizona area. It used to be an 18-mile drive to get to the Broken Arrow Baptist Church, which they attend in Pearce, but now it’s 28 miles, she said.

She said she doesn’t understand why new wells need to keep going into the area, and be joined by huge center pivots, that sprinkle the water onto corn, alfalfa and pecans and pistachio trees.

“We live in a closed aquifer. We rely on rainfall, whatever water comes out of the sky. It’s not replenished by rivers and streams,” she said while walking along one of the fissures. “I don’t understand why all these irrigation wells need to keep going.”

“Crisis point”

Tara Morrow said she will sign the petition to create an Active Management Area once the Cochise County Recorder’s Office determines what would be the exact boundaries of the area in the Willcox Basin where she lives and how many registered voters live there.

Once all that’s done, “We are going to hit the pavement with petitions and be out at community events,” said Beau Hodai, campaign manager for the AMA drive.

“It seems pretty much anywhere you go, and you talk to people, pretty much the constant subject is water and agricultural interests coming in from out of state to sink more wells. People’s wells run dry. People talk, and say ‘they will move before my well runs dry.’

“It’s reached a crisis point. It’s obvious our lawmakers aren’t going to do anything, and the executive branch is not going to do anything,” he said.

The Douglas Basin already is a state-designated Irrigation Non-Expansion Area that doesn’t allow new farming on land that hadn’t been irrigated before that area was created in 1980. But that only keeps out new irrigation, doing nothing about existing groundwater pumping that’s lowering the aquifer, he said.

Peggy Judd, the county supervisor representing the Willcox area, opposes creating the state-run management area. Raised on a farm, she’s been a long-time supporter of the Riverview Dairy and other agriculture there although more recently she has turned to support some kind of regulation — just not an AMA, she said.

“I don’t think an AMA will work. Look at the list of cities in the AMAs and they they all have (Central Arizona Project) water. Some of them have rivers and canal systems that have been in existence for generations.”

“Douglas and Willcox only have just what is under the ground. We don’t have an outside source,” she said.

Judd is backing state legislation to allow county governments to set up local groundwater management areas to establish rules governing groundwater pumping.

“I want some control over the groundwater,” said Judd, who said she’s made that clear by testifying at a hearing this month run by state Rep. Regina Cobb, a Kingman Republican who has unsuccessfully tried for several years to push that and similar bills through. “I’m not against regulation.”

Rep. Gail Griffin is a Hereford Republican who has blocked Cobb’s bills in the Natural Resources, Energy and Water Committee that she chairs. Griffin said the bills don’t call for a public vote, and “other issues in the bills were not acceptable.”

In an email to the Star, Griffin didn’t say if she would support an AMA or a nonirrigation expansion area.

“Normally, AMAs were designed for high growth areas. That doesn’t mean there are not things we need to consider to address the recharge deficit we have had from 25 years of drought. Water basins don’t follow county boundaries,” she said, adding, “Establishing an AMA or an INA is forever … in perpetuity.”

Fissures around Parker Ranch Road, east of Kansas Settlement Road on the east side of the Willcox Basin

Cheryl Knott, Willcox Basin campaign leader for the AMA petition effort, disagreed with Judd that such a program wouldn’t work because the Wlllcox area has no CAP supply. She noted that the state-run areas for Santa Cruz County and Prescott also lack any CAP supplies.

She said she’s been motivated by watching several large land parcels near where she lives in the Pearce-Sunsites area being sold and nut trees being planted in them or the land being cleared for tree planting. “In the meantime, I’ve had a couple of neighbors whose wells have gone dry,” Knott said. “It’s very concerning.”

Finally, Nav Athwal, managing director of Trinut Farms LLC, which grows pecans near where the Dragoon Road fissure opened, said he’s all for regulation of pumping. Trinut is based in Ceres, California, in the Central Valley agricultural belt.

He declined to say if he would support AMAs other than he thinks an Irrigation Non-Expansion Area may be more appropriate for a rural area. He declined to discuss the fissure, saying, “I don’t know enough about it.”

“I think regulating groundwater is a good thing for both the farming community and residents,” he said. But, “whatever regulation did come forward would have to take into account existing water rights that farmers spent a lot of blood, sweat, energy and money acquiring.

“No one wants to see wells go dry. No one wants to see the food ecosystem go away or jobs go away,” he said.

Tucson is looking pretty green! Check out the views from Sabino Canyon following this summer's above-average rainfall.

Make sure to check the weather before heading to Sabino Canyon as some trails and areas may be closed due to flooding.