Along with the many wrenches the pandemic has thrown into the works of Pima County’s justice system, it also produced unexpected benefits, officials from several local court branches say.

A week after newly elected Pima County Attorney Laura Conover took office at the start of 2021, the prosecutors’ office was the subject of a coronavirus outbreak. For the first time in its history, the office was forced to close its building.

“It was extraordinarily painful for a brand new administration to close the building, but we also learned so much,” Conover said. “COVID pulls back layers on systems that I think we haven’t looked at in years or decades, in every aspect of the criminal justice system.”

Conover, Nate Wade, the assistant public defender, and Tina Mattison, deputy administrator of Pima County Juvenile Court, participated in a virtual panel Thursday about courtrooms before, during and after COVID-19. The panel was part of John Jay College of Criminal Justice’s “Justice in the Southwest” symposium.

The abrupt shift to work-from-home posed major challenges to an office that was not yet paperless, said Conover, the second defense attorney to hold the position of Pima County’s top prosecutor. Converting the office from paper to digital is one of Conover’s initiatives.

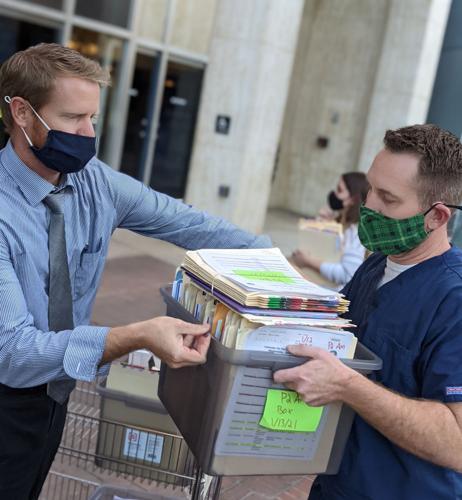

“It truly was in intense moment,” Conover said of the closure, which lasted from January 10 through 19. “As we literally moved boxes of paper on dollies down elevators and out the front door in an assembly line in front of the building, night after night. As painful as it was, what an unbelievable learning opportunity.”

The closure resulted in files needing to be transferred to and from attorneys working from home every morning and night, to ensure they had what they needed for online court hearings. Dan South, who was recently appointed chief of the office’s criminal division, was a big part of the reason the office kept functioning, spearheading efforts to ensure lawyers had what they needed to appear in court, Conover said.

But South’s hard work didn’t start there. When the pandemic first began, and months before Conover was elected, South created a triage system where defense attorneys could bring plea agreements to him for quick processing, helping to get defendants released from jail on credits of time served.

Assistant Public Defender Wade called South “the hero of that office,” for the actions he’s taken to keep cases moving throughout the pandemic.

Rethinking incarceration

Pima County’s public defender, county attorney’s office, pretrial services and the courts worked together to significantly reduce its jail population in the weeks following the start of the pandemic. Wade said it was the most immediate challenge his office faced.

“Some of the most terrifying phone calls I’ve ever received were during that time,” Wade said, adding that clients inside the Pima County jail and their family members were “legitimately scared” about the health risk.

Twenty public defenders spent three, 12-hour days over a long weekend, reviewing the cases of office’s incarcerated clients to see if they could be considered for release because of the pandemic.

Court administrators, the presiding judge and the attorneys’ offices “galvanized quickly” to set up a system to get people out of jail. The team met weekly and made a concerted effort to rethink release conditions.

With in-person hearings shut down, the court system has stalled around the country, and Pima County is no exception.

While this isn’t ideal for the swift delivery of justice, it has allowed overworked public defenders to spend more time with their clients and on their cases.

“That made a huge difference in our ability to serve our clients, and our ability to do more research,” Wade said. “It really, to me, was a great opportunity to see things that maybe I’d been missing in the past when I was dealing with pressure.”

That extra time allowed Wade and the other lawyers in his office the ability to get a better understanding of their clients, and the shift to Zoom meetings drastically increased the “show rate” for meetings.

From courtrooms to Zoom rooms

Pre-pandemic, Wade said maybe 20% would show up for in-office meetings. Online, the show rate is more like 90%, Wade said.

The office is likely to continue using Zoom for meetings that don’t require clients to be at the office in person, which will be a game-changer for clients who don’t have ready access to transportation, Wade said.

The juvenile court system also saw success with the move to telephonic hearings and judges are looking into what’s best, moving forward, Deputy Administrator Mattison said.

“We think there’s going to be a hybrid coming back,” Mattison said. “We want to do some things in person, but some things, we’re finding that anecdotally, parents are showing up more to some of their dependency hearings. Parents that we hadn’t seen in years. That tells us we can’t go back to exactly normal.”

The pandemic also provided some major shifts in their caseload in both dependency, or custody, cases, as well as cases involving minors accused of acts that are considered crimes for adult defendants.

In 2019, there were 1,116 dependency petitions filed through the court. That number increased to 1,262 in 2020, with Mattison saying that the increase is believed to be due to teachers gaining additional insight into a child’s home environment through the shift to online classes.

On the delinquency side, there were 5,522 cases referred to the court in 2019, versus 3,292 in 2020. Of those cases, many were resolved through diversion, but the number of cases that advanced through the courts also dropped from 1985 in 2019 to 1388 in 2020.

The thinking on that end is that with kids not attending school in-person, they were less likely to be out with their peers and causing trouble, Mattison said.

The juvenile court’s goal has long been to find the best way to keep kids out of the system and detention, and the pandemic pushed people even harder to try to catch child welfare cases before they end up in the courts.

Mattison nodded to the collaborative nature of the court, saying that they worked hard with other agencies and advocacy groups to figure out how to best meet the needs of participants moving forward.

“That collaboration between our justice partners... was the biggest thing that got us through this pandemic,” Mattison said.

The collaborative efforts to assist people caught up in the system continue, as for the second time since the pandemic began, multiple agencies have come together to evaluate the jail population and release people who don’t need to be there, Conover said in a interview Friday.

Her office is also working on an initiative to try to get people out of jail who are being held on detainers from other jurisdictions.

“It’s incumbent on us to learn from this last year and not just knee-jerk revert back to normal. Normal wasn’t healthy,” Conover said. “There’s no reason why Arizona has to break incarceration rates. There’s no reason why we need to continue the war on drugs here, when no one else is.”