With each stroke of her wide painter’s brush, more and more dried, coarse dirt is pushed aside, revealing a new layer with every motion.

Wisps of dust hang in the air as, little by little, a small, round urn comes into the light in the now-blackened chamber of the adobe mission built in 1952 by famed artist Ettore “Ted” DeGrazia.

In her right hand, art conservator Charlie Burton, passes her brush back and forth all around the urn. Nearby, she keeps a scooper that is normally used to pick up cat litter. It’s at the ready to sift through the dirt and separate any artifact that is hidden from view.

It is early December and for the first time since the fire, which devastated the chapel last Memorial Day, May 29, the urn has been unearthed.

But it is no longer the same chapel.

The Mission in the Sun, at 6300 N. Swan Road, honoring Father Eusebio Kino and dedicated to the Virgin of Guadalupe, no longer bounces and filters Tucson’s harsh sunlight that once spilled through its huge, open ceiling. Where brilliantly colored murals painted by DeGrazia were splashed along its walls, whole sections of the plaster are now bare and the sun-dried adobe bricks he used to build his beloved mission show streaks of the yellow straw that was used to hold them together. Some of the wood beams have a deep, black, gator char rippling their surface.

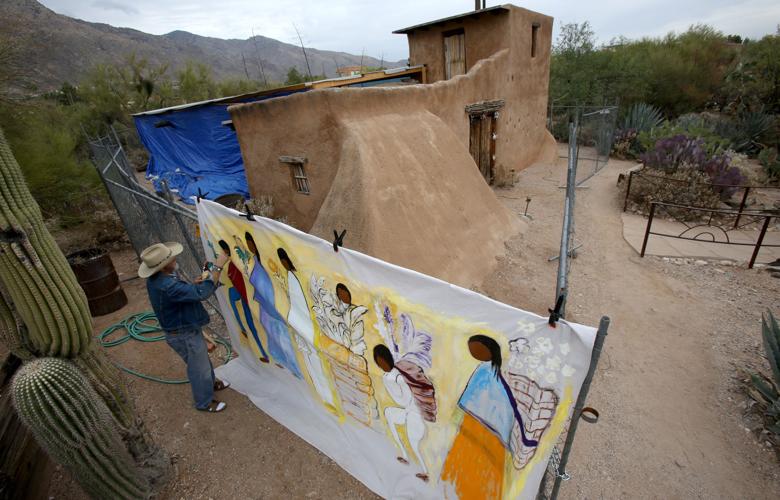

In front of the chapel, behind its brown adobe façade, a wooden frame covers the rear of the building with a blue tarp that protects the mission from the elements. Inside, it is now dark and subdued, with metal and wood posts holding things together.

On occasion, Burton visits the chapel to salvage what she can, but still finds the old mission special.

“It has always felt like such a sacred place … always has been,” she says. “There’s such an aura about it.”

Since 2005, Burton has been the conservator at the DeGrazia Foundation, cleaning and preserving many of the paintings in the gallery.

Since the fire, she has devoted herself to “save every piece of the murals that I can,but because they’re so fragile, I can’t stick them all up like a puzzle and try to put them together.”

All the murals inside the mission were damaged in the fire, Burton says, especially at the altar where there was an image of the Virgin and where, it is believed, the fire originated.

It was most likely started by a candle or candles that were on the altar that evening, Burton says. It was after hours, she says, and no one was on the property, so it took a neighbor to finally see the flames.

The fire may have smoldered at first, burning its way into some of the wood, which had been treated with creosote.

“So it had a lot of accelerant to burn deeply into the wood of the chapel, and in turn, to the paintings.”

As the story goes, when DeGrazia started building the mission in 1950, he and several Yaqui friends worked on it for two years.

The land, at the base of the Santa Catalina Mountains, was remote and isolated at the time, and all the adobe bricks were made on the site. A big hole was dug and water had to be hauled there in a Ford Model A. It’s said that all manner of fill was used to mix with the mud: straw, rocks, perhaps some beer bottles.

With the restoration process to repair the mission set to begin, possibly by next spring because of unforeseen delays, Burton recognizes that they may lose even more of the murals because the plaster has moved away from the wall and has become loose with vibration.

Another thing: She cannot clean the surviving murals.

“They’re all charred. It’s a water-based paint he used, and if you use mineral spirits, that will only stain it. If you use water, it would wipe it off. It wouldn’t be damaged. … It would be gone.”

Still, she wants to save as much as possible.

Some of the wood beams that were badly damaged will have to be replaced and the walls replastered, but what is left of the murals will remain as they are.

A lot of artists have called to say they would replace the murals with “DeGrazia-esque” paintings, but this is different. “I don’t think another artist should do it.”

There have been small repairs on the murals before and there is some new work where the chapel leaked, but this damage is severe, Burton said.

“Ted would’ve slapped something on (the wall) again. He’d have gotten out the Chivas Regal and would have painted it in a day because he (already) changed that chapel a few times.”

She has seen evidence of where he painted over previous murals. “There’s a piece, I think it’s a cross, up near the altar on the left side, there is a painting under another painting.”

What Burton is confident about, though, is the text that was in back of the room.

“We will definitely reconstruct the wonderful poem he (DeGrazia) wrote about the Virgin of Guadalupe. It’s all lettering and I think I’ve got 85 percent of the pieces of it. We don’t think Ted would mind.”

Most of the altar is down to bare adobe that crumbled from the fire as well as from water damage when firefighters extinguished the flames, encasing many of the mementos in mud.

It may be how they managed to escape destruction in the flames.

Burton has so far uncovered cherubs, crosses of various sizes, damaged or melted picture frames, remnants of glass votive candles, figurines and other memorabilia.

What to do with these items that survived the fire is in question.

Over the years, when too many mementos, such as photographs, messages, poems and other relics were collected around the altar, they were buried on the property.

Lance Laber, the executive director of the DeGrazia Foundation since 2005, is also well-acquainted with the tradition, especially since he was the one who started it. He has been burying artifacts on the grounds for years.

It was not uncommon for relics to be left on the altar. Some would be left there for years, he said. But eventually most of them had to go because they presented a fire or safety hazard.

But this time, things are different. He is pondering saving the salvaged pieces because, “Now, they are part of the history of the mission.”

The destruction of the chapel has been hard on Laber. “It’s a personal thing for me. I have been taking care of that mission for 36 years.”

His daily routine usually includes looking around the grounds every evening at 4 p.m. as employees leave for the day.

However, he was on vacation in Kino Bay when the fire broke out. “It was one of those things. I wasn’t there to go check it out,” he said, his voice trailing.

His ties to Ted DeGrazia go back to his childhood.

When he met the artist, he was “a rotten little kid,” he said.

Laber was a friend of DeGrazia’s stepson, Hal Grieve, starting at the age of 5.

Laber fondly remembers when DeGrazia brought a lump of modeling clay so he and his friends could play with it.

“It was a great memory.”

“Hal was on our board for 45 or 50 years and he just passed away last Dec. 2. He was an important guy to the gallery and foundation. Without Hal, the gallery might not be here today.”

Both Laber and Burton hope people will again enjoy the the chapel when it is restored, and they want to protect it and make it better than in the past.

Burton thinks finding a way to use electric lights may be a good option.

Laber, too, is unsure, but thinks, “I may add a candle holder or rack like you’d see in the San Xavier (Mission) or in a typical Catholic church. … I just need to find a solution to make it safer.”

They have also talked of installing a sprinkler system.

Laber would like for it to remain open 24 hours a day, seven days a week as it was in the past, but acknowledges the insurance company may have the last word regarding the safety of the building.

Also, the mission is part of the DeGrazia Gallery in the Sun Historic District and since 2006 has been on the National Register of Historic Places, Laber said. They still need to hear from register and get its input as to how to proceed, Laber said.

When the restoration does start , the project is not expected to take long. When it is finished, Laber hopes to have a grand reopening, letting everyone in the community know that it is back.

That said, Laber admits the mission will never be what it was as far as the art goes.

“It will be restored as best as it can be and the hope is that everyone will use it the way they always have in the past.”

In the meantime, Laber has other concerns important to the future of the foundation and DeGrazia’s legacy.

Its biggest challenge now is to introduce DeGrazia to the next generation.

He has been dead for 35 years, Laber noted, and the challenge is to get new fans to appreciate and understand what and who DeGrazia was and why they bring students, from second-graders to those in college, to see his work.

“We have been somewhat successful, but we can’t stop.”

Just the same, Laber appreciates the community’s support. “We would like people to come to the gallery, enjoy it and use it as a resource.”

And even if it may end up being slightly different, “It will forever be DeGrazia’s mission.”

Conservator cleans, preserves DeGrazia

legacy for new show

One of the perks Burton has as a conservator is that she is able to get up close and personal with all kinds of art.

So close, she can actually touch it. That’s her job.

Burton’s objective is to preserve any and all types of art by cleaning, using various techniques.

“I don’t restore them,” she said. “I don’t try to make a picture perfect, but I try to preserve as much as I can of the original.”

The process allows her to become intimate with each piece and, in some ways, with the artist.

As the art conservator for the DeGrazia Foundation and his Gallery in the Sun since 2005, she understands DeGrazia’s methods and feels not just a physical attachment, but an emotional one as well.

“I’ve been working with him for so many years now, I’m hoping he’s happy with what I’ve been doing,” she says.

It brings her joy, and she says she hopes the work she has saved is around for generations.

Burton recently finished a series of paintings DeGrazia made using the encaustic method. The encaustic style is also known as hot wax painting involving heated wax and paint.

“This is the first big encaustic show we’ve done,” Burton said. “Ted did them for several years, mostly in the ’50s, and he was experimenting with different materials. He did a lot of the Virgin of Guadalupe.”

This will be an opportunity to introduce the public to another medium and to show DeGrazia’s expertise in the process, she said.

The show is scheduled from Jan. 26 through Sept. 7 in the rotating gallery at the DeGrazia Gallery in the Sun, at 6300 N. Swan Road.