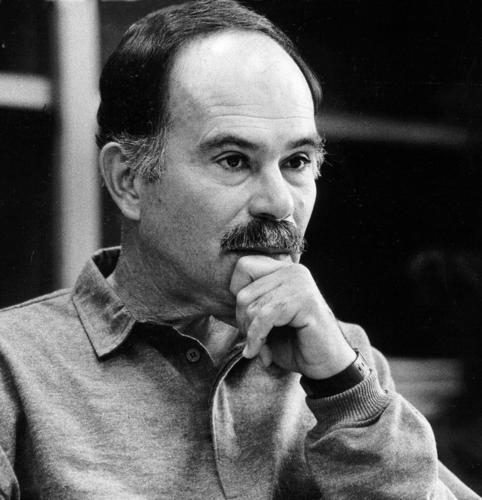

After 25 years of balancing testimony and evidence, listening to attorneys, dealing with fine points of law, and issuing often life-changing decisions, Gilbert Veliz gave up his gavel for retirement.

But the former Pima County Superior Court judge didn’t give up on weighing facts, researching information and reaching conclusions. He plunged into a long-held desire to write a book.

Veliz, a 1961 graduate of the University of Arizona College of Law who was appointed to the bench by former Gov. Raúl H. Castro, retired in the late 1990s.

Then he spent 10 years delving into the 1910 Mexican Revolution, a turbulent period during which tens of thousands of Mexicans fled the strife and settled north of the border, in relative safety.

The result of his laborious endeavor is “The Flight of the Deer,” a sweeping historical fiction filled with larger-than-life characters of the revolution and a Mexican-American photographer who explores this period and comes to understand his family’s history, reaching back to upheaval.

Curiosity led Veliz to immerse himself in books and research and the disciplined task of writing, said the 78-year-old father of five and grandfather of 10.

“I wanted to tie historical facts together, try to bring truths,” said Veliz, a resident of Barrio Menlo Park for nearly 60 years.

The central character in Veliz’s story is Ricardo, born into a Southern Arizona Mexican-American mining family. Ricardo, chasing whispers of his family’s history and using old photographs, plunges into the past.

Like Ricardo, Veliz came from a Southern Arizona Mexican-American mining family. His parents, who were born in Sonora, made a home in Bisbee where Veliz’s father worked in its fabled copper mines and where the future judge was born.

Despite the similarities, Veliz said his book is not a shadow autobiography of him and his family. He said he did not write his book for vanity but only to expand the knowledge of our borderlands and to share it with anyone interested in understanding our regional history.

“It’s an appreciation of what happened,” he said, adding that too many people do not know the history that binds our two countries.

Moreover, he added, “I want my kids and grandkids to know why they’re here and what happened.”

The Mexican Revolution was the world’s first major social and political volcano of the 20th century.

Its roots stretch north across the border, where political opponents of the Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz, like the Flores Magón brothers, stoked revolutionary fires through their publications and public appeals. Several years before Díaz stepped down in 1911 under growing pressure, Mexican miners, who were paid less than the American miners, went on strike at the American-owned Cananea Consolidated Copper Co. in Sonora, just south of Bisbee-Naco. Mexican soldiers, with help from Arizona Rangers summoned by the mine’s owner, Colonel William Cornell Greene, one of the richest men of his time, violently put down the strike.

But Veliz’s book is also about other facets of the revolution: the genocide of Sonora’s Yaqui communities and the exodus of Yaquis to Southern Arizona, where they settled in communities in Tucson, Marana and Tempe; and the Cristero War of 1926-1929 when the anti-clerical Mexican government attacked Catholic power and institutions, burning churches, killing priests and nuns, and inciting armed revolt by Catholics, aided by their allies in the United States.

These historical forces reshaped Mexico and the American Southwest. The clearest consequence are the families of Southern Arizona who are here because earlier generations were displaced.

Once here, these families settled, grew and contributed to U.S. society and economy. Once here, they expanded their families, worked in the mines, railroads, ranches and cities. They educated their children and their children, attended church and built strong communities.

“It’s everybody’s story,” said Veliz.