Located 35 miles east of Flagstaff and 6 miles south of Interstate 40, Meteor Crater and its fragments were first recognized after the discovery of iron fragments west of the crater near Canyon Diablo by a local shepherd, Mathias Armijo, who misidentified them as silver.

Upon further research from the University of Pennsylvania, the fragments were reported as having a composition of 92 percent iron, 7 percent nickel, with a remainder of cobalt and trace elements of platinum and iridium.

Early misconceptions involving the crater’s origin included the opinion of G.K. Gilbert, chief geologist of the U.S. Geological Survey, who upon examination of the crater in the 1890s said it was formed by a steam explosion rather than a meteorite impact.

His reasoning was based upon the lack of an identifiable object as big as the crater itself, along with the absence of sufficient displaced rock material at the site.

Classified as the youngest meteor impact site in the world, out of more than 150 known terrestrial impact sites, Meteor Crater, 150 feet above the surrounding plain, measures 4,000 feet wide. Modern scientific research has concluded that several hundred thousand tons of iron and nickel estimated to have broken off from an asteroid a half-billion years ago traveled at a velocity of close to 40,000 miles per hour prior to impact 50,000 years ago at the current site. The bulk of the original object, believed to have measured 150 feet in diameter, vaporized during descent into the atmosphere. The explosion of the impact is estimated as having a force exceeding the explosion of 20 million tons of TNT.

The Canyon Diablo meteorite is also referred to as the Barringer meteorite after the Philadelphia lawyer and mining engineer Daniel Moreau Barringer. Barringer firmly believed the crater was the result of a meteoric impact. Enticed by the prospect of finding a large body of iron and nickel beneath the crater floor, Barringer and partner Benjamin C. Tilghman formed the Standard Iron Co. in 1903, after obtaining a patented group of mining claims on 2 square miles of land signed by President Theodore Roosevelt. S.F. Holsinger, a former Forest Service employee in charge of the exploration, discovered the largest meteorite at the site, weighing 1,406 pounds. Additional discoveries followed, including one specimen weighing 1,050 pounds and another weighing 1,000 pounds.

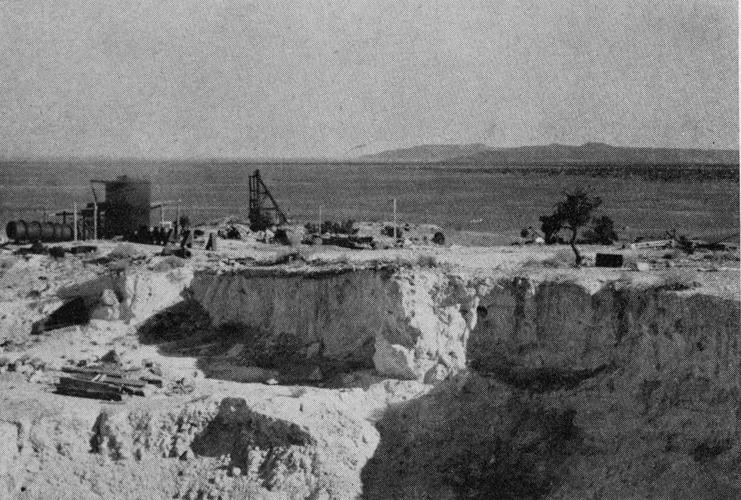

Barringer invested more than half a million dollars in an extensive onsite drilling program over several decades in the sandstone and limestone beds, including a shaft reaching a depth of 1,376 feet. Barringer’s commercial venture was over, however, once churn drills were impeded by masses of meteoric material composed of oxidized meteoric iron below 1,250 feet.

A short-lived mining operation that involved a group of Phoenix investors in the late 1940s worked the high grade (99.7 percent) silica sands on the southerly slope of Meteor Crater for use in the flint glass industry. The sand was processed at Sunshine Station, on the main line of the Santa Fe Railroad 6 miles north of the crater. There, the necessary pulverizing, screening and conveyor equipment was available to accommodate the deposit.

Southern California proved a viable market for silica sand, which comprised 70 percent of its finished glass product. Ball Brothers, a glass manufacturer in El Monte, successfully applied silica sand from the crater to its product. Attempts to use crater silica sand in Arizona for steel foundry work proved disappointing because of its characteristic of breaking down under heat required for steel casting.

A major discovery in 1960 by Eugene Shoemaker was the presence inside the crater of coesite, a high-pressure form of silica (SiO2) and stishovite. The presence of these minerals confirmed Barringer’s hypothesis since these minerals could only be created through impact and not through volcanism.

The crater currently measures 550 feet deep, 200 feet less than it did after the original impact, because of the accumulation of rock and soil through natural weathering processes. More than 15 tons of meteoritic material reportedly has been recovered from the site. Since the 1960s, the crater has served as a training ground for the Apollo astronauts, a backdrop for Hollywood movies, and the tourist attraction it is today.