Hudbay Minerals Inc. plans to start early construction work on the Rosemont Mine in June, on utility lines to get water and power to the site and some “minor” drilling at the site, a company lawyer told a federal judge Thursday.

That could set the stage for a legal conflict over a construction timetable between Hudbay, federal agencies that approved the $1.9 billion mine project, and opponents who have filed five lawsuits to challenge it. Or, there may be a compromise agreement, delaying construction to a date that both sides will accept for now.

U.S. District Judge James Soto asked attorneys for Hudbay and for mine opponents to try to find common ground on a construction start date, after opponents said that if Hudbay proceeds on its stated schedule, they would try to seek a preliminary injunction blocking construction relatively soon. Attorneys for both sides said they would try to reach agreement.

At Thursday’s hearing, Hudbay attorney Norman James said the company wants to get moving on the project after waiting 12 years to obtain all the needed permits. It plans to spend about $100 million over the next six months, he said.

The company has agreed to give opponents’ 30 days notice before construction starts, to allow them time to seek an injunction.

Attorneys for opponents want construction delayed at least until the judge can rule on the merits of three of their five lawsuits against the project — suits now pending since 2017. That could happen by the end of this summer, Soto told attorneys at a conference at the federal courthouse in downtown Tucson.

And while Hudbay attorney James said most early ground disturbance for the project will be relatively minor, opponents said they’re concerned that some could “irreparably” harm tribal cultural sites.

Thursday’s conference dealt with three lawsuits by environmental groups and two by tribes. All seek to overturn three past federal approvals for the open pit copper mine in the Santa Rita Mountains southeast of Tucson.

The most recent approval was the March 8 Army Corps of Engineers decision granting a Clean Water Act permit for the mine.

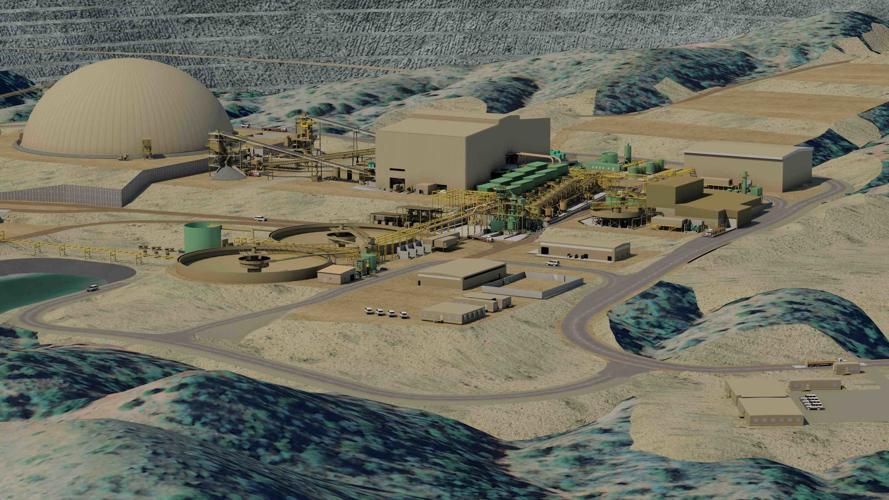

Rosemont would operate for close to 20 years on more than 5,000 acres of public and private land, 30 miles from Tucson.

Plaintiffs include the Tohono O’odham, Hopi and Pascua Yaqui Tribes and the groups Save the Scenic Santa Ritas, Center for Biological Diversity, Arizona Mining Reform Coalition and the Sierra Club.

James laid out these construction plans:

- Drilling of 36 holes starting this summer at the main mine site, primarily in the area of the open pit that would span more than a mile and go a little more than a half mile underground. About 2.8 acres would be disturbed.

- Building an underground pipeline to take water from company wells in Sahuarita over the Santa Rita Mountains to the mine site.

- Building a high voltage power line to take electricity from a Tucson Electric Power generating station in the Sahuarita area to the mine site. It will follow essentially the same route as the pipeline.

- The company will build intersections at the mine site and Arizona 83 starting in June to accommodate vehicles entering and leaving the site.

- At the Sonoita Creek Ranch in Santa Cruz County that Hudbay has purchased to mitigate mine impacts, the company has started salvaging plants and building fences.

The company doesn’t expect to do any major clearing or grubbing work at the mine site until fall 2019, at the earliest, James told the judge.

The utility line work will affect some archaeological sites. Some are historic sites that include many “mining-related” properties from that area’s history of mining dating back to the 1870s, James said.

Others are prehistoric cultural sites, important to tribes, lying under the water pipeline route. Drilling there will be on the site’s edges and “I don’t anticipate a short-term substantial impact,” James said.

But Stu Gillespie, an attorney representing the tribes, said eight archaeological sites lie under the utility line corridor. He said impacts to them during construction will be “severe, irreversible and permanent.”

“There’s no way to recreate” the tribes’ spiritual and cultural heritage at the sites if they’re destroyed — “once it’s gone, it’s gone,” Gillespie said. “We cannot mitigate desecration of burial sites.”

Roger Flynn, an attorney for the environmental groups, said, “We would hope that for a project that’s been pending for 10 to 12 years, the company will wait up to 10 to 12 months” for the judge to rule on the earliest lawsuits.

James said the company already has been “very patient,” waiting for permits to be granted.