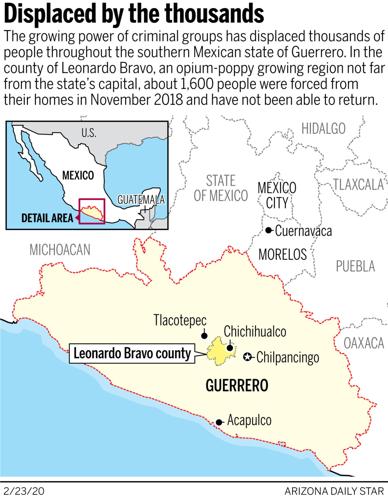

Leonardo Bravo, Guerrero, Mexico — So many people have been forced from their homes in this highland area of southern Mexico that the mayor gives a form letter to local residents who want to seek asylum in the United States.

Citizens contemplating an asylum claim can get a form letter from Mayor Cástulo Guzmán attesting to rampant violence in his county.

In the last 14 months, Mayor Ismael Cástulo Guzmán told me, he’s handed out around 600 of them. The formal document explains:

“Due to clashes between armed groups and organized crime in the area of the county of Leonardo Bravo and in the state of Guerrero during recent years, there has been a wave of violence that has kept society in fear and prevented residents from carrying out a normal way of life.”

Displaced people, forced from their homes by armed groups, can take these letters to Mexican cities on the U.S. border to help them make an asylum case.

In some of these border cities, exiles from Guerrero and neighboring Michoacán, not Central Americans, make up the bulk of the people waiting on the list to make an asylum claim. In Nogales, Sonora, early this month, 40 percent of the people waiting for asylum appointments with U.S. officials were from Guerrero.

The Mexican government, though, continues to treat migration as mainly a Central American problem.

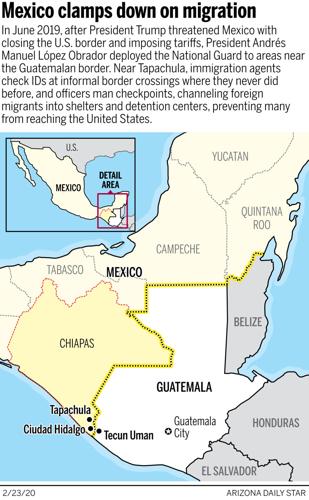

In June, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and his government reacted to threats from President Trump of closing the U.S. border and imposing tariffs by reversing his initial, more liberal migration policy.

Now, Mexican immigration agents check IDs at informal crossings on the Guatemalan border where they never did before.

Soldiers and other officials man highway checkpoints in the south and corral foreign migrants into shelters and detention centers. One shelter I visited earlier this month in Tapachula, Chiapas, near the Guatemalan border, teemed with more than 700 people in a complex meant for 250.

During his daily press conference on Feb. 7, I asked López Obrador why the government has taken such drastic measures to slow Central American migration but done so little to prevent Mexicans from Guerrero from being forced from their homes by armed groups. He claimed Mexican migrants are fleeing primarily for economic reasons.

“In the majority of cases, it’s because of poverty, it’s due to the lack of opportunity,” López Obrador said. “There are seven principal causes (of migration). Out of these seven, the main one is necessity — nobody leaves because they want to.

“That’s why it’s so important that we are investing in development programs in the poorest areas of Mexico, so that migration is optional, not forced as it is right now. I hope we resolve this soon — we’re working with a plan.”

I’ve spoken with displaced people from Guerrero passing through Tucson, in Tijuana, in Nogales, and in the state itself, and they’ve consistently disagreed with this diagnosis.

The Mexican migrants of 15 years ago were mainly motivated by economic needs, but today’s Mexican refugees, though poor in most cases, are fleeing from gunbattles and extortion, more than poverty. They want simply to return home.

For López Obrador to grapple with the true causes of today’s Mexican migration, though, would mean confronting the most difficult problem in Mexico today — public safety.

In comparison, stopping Central Americans from reaching the United States is easy, and popular.

“They’re Carrying away the dishes”

The U.S. State Department tells Americans “do not travel” to Guerrero, the home of the once-popular beach resort Acapulco.

Gunfire, more than poverty, drives the exodus from the southern state of Guerrero, say those who left. Above, state police search for survivors after a gunbattle in Leonardo Bravo in 2016.

“Crime and violence are widespread,” the travel advisory says. “Armed groups operate independently of the government in many areas of Guerrero. Members of these groups frequently maintain roadblocks and may use violence towards travelers.”

Journalists in Mexico know that working in the capital city, Chilpancingo, and Acapulco is generally feasible, but travel beyond that into the mountains requires careful planning and often the prior approval of whatever armed group runs the area. In the Sierra, or highlands, of Guerrero, these armed groups serve as the de facto authority.

Often called “organized crime,” “self-defense,” or “drug trafficking” groups, they may actually amount simply to conquerors — groups that take over territory in the highlands and make money however they can off the residents and their property.

In November 2018, an armed group swept into the highland villages of Leonardo Bravo, which surround the county seat of Chichihualco.

At least 1,600 people fled their homes. Hundreds migrated down the mountains to Chichihualco, others went beyond to Mexico City or even the U.S. border. Some have made it across and are pursuing asylum cases in U.S. immigration court.

Mayor Cástulo Guzmán, who oversees the entire county of Leonardo Bravo, is from one of those highland villages, but only returns these days as a visitor, he told me.

“I’m another displaced person, even though I’m mayor,” he said. “We’ve been sacked, we’ve been robbed. Our belongings, the little we had, they took from us.”

But while the mayor has the privilege of at least visiting his home village, other displaced people told me they have been unable to return.

Many of the 1,600 driven from their homes in Leonardo Bravo have moved to the county seat of Chichihualco, above. Others dispersed to Acapulco or Mexico City, or made the journey to the U.S. border. Nearly half of those waiting in Nogales, Sonora, for asylum appointments in the U.S. are from Guerrero state.

I spoke to a pair of displaced siblings-in-law, María and Luis, in Chichihualco. I am not giving their full names because their lives are threatened by armed groups.

Around a year after they were forced from their homes, María, Luis and the other displaced people were told by government officials they could go home. They formed a caravan and drove up into the mountains, but as they arrived, gunfire rang out. The caravan turned and fled back down.

“They want to take over our land, since we’re not on our lands now,” Luis said. “They’re harvesting the products. They’re in the houses. They’re taking the windows. They’re carrying away the dishes.”

María, Luis and thousands of other displaced people across Guerrero are waiting for the federal government to do something, anything.

Citizens disrupted by violence in the Mexican poppy-growing region say the federal government has looked the other way.

The president, María said, “should use an iron fist so that we can return to our villages. What we are fighting for is to return to our villages. We’re working people. We have land up there, our heritage.”

What should be done?

“Get those people who call themselves ‘community forces’ out of our villages. Organized crime is what is in our villages.”

Bishop under threat

If only it were so simple.

But Bishop Salvador Rangel, who leads the diocese of Chilpancingo and Chilapa, said it isn’t — not in Leonardo Bravo or anywhere in Guerrero where villages and towns are disgorging their residents in the face of armed exploiters.

Rangel has become famous, or notorious, in this part of Mexico for intervening in conflicts by negotiating with leaders of organized crime groups.

But you won’t see him in Chichihualco, the county seat of Leonardo Bravo, because he prefers to go there undercover.

“I’ve spoken with many drug-trafficking groups to try to achieve peace and tranquility, of which there isn’t enough with so much crime in this land.

“But right now I’m under threat from the community forces of Tlacotepec (who occupy the villages of Leonardo Bravo), because they accuse me of being partial, that I’m supporting the other group in Chichihualco. What I say is, ‘I’m opposed to them having displaced these people.’ “

Bishop Salvador Rangel takes on the role of peacemaker but feels under threat.

The area’s economy has for years been dependent on growing poppies to produce opium paste, the raw material out of which heroin is made and eventually sold in the United States. But in the last couple of years opium-paste prices have plunged as synthetic opioids like fentanyl have captured more of the market.

That crisis has lowered incomes at the same time armed groups assert ever greater control. They often put up roadblocks along the rural roads into towns and may force residents to seek permission just to travel.

Similar dynamics govern much of Guerrero, as well as the neighboring state of Michoacán.

Residents of 20 villages in the Sierra of Guerrero arm themselves to form a community self-defense force in 2018. This force was later ousted by another community force.

It’s turned so bad that in January one mountain village unveiled a self-defense force made up of the male children, as young as 6, though only boys over 12 carried real weapons.

“Now, many of the communities in the Sierra are simply ending up empty,” Rangel said. “The authorities, very weakly, have done nothing. They haven’t done anything so that people can return.”

The people, he said, “have migrated to the cities. For example, many come to Acapulco, to Chilpancingo, they go nearby to Cuernavaca, to Mexico City, but many people are going to the United States.”

Poppy farmer applies for asylum

One of them is a poppy grower named Crescencio Pacheco. In November 2018, he fled a village in Leonardo Bravo called Campo de Aviación with his wife and three children.

After arriving in Chichihualco, he eventually led displaced people on a protest movement to Mexico City. They set up a camp outside the National Palace there for 39 days, Pacheco said. Finally the government made some promises and convinced the protesters to go back to Chichihualco.

“It was a complete lie,” Pacheco told me by phone. “They wanted to get us away from the National Palace. It was a trick.”

As time went on and Pacheco continued agitating for the displaced people, he eventually received threats, he said.

In July, he fled with his family to Mexico City. From there, they went by bus to Nogales, Sonora, where he knew other displaced residents of Leonardo Bravo had gone.

Near the port of entry, they got on the list for an appointment with Customs and Border Protection, and after six weeks they were at the DeConcini Port of Entry, explaining their situation.

The American officials treated the family well, Pacheco said, kept them in the port for a day or so, fit Pacheco with an ankle bracelet and sent him on to Phoenix. From there, the family went to live with family in another state and pursue their asylum claim.

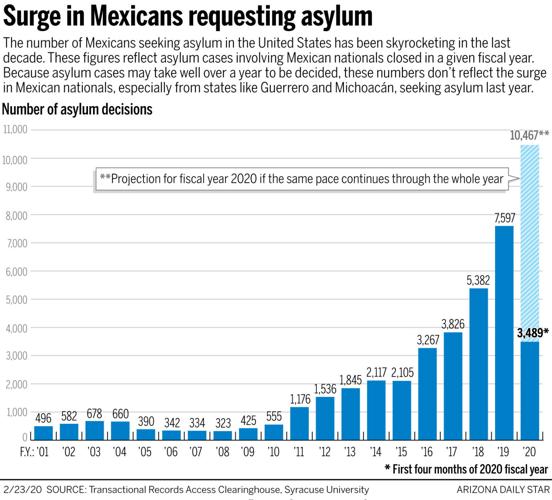

It’s very hard for Mexicans to win asylum, El Paso attorney Carlos Spector told me. Indeed, of the 7,606 Mexicans whose asylum cases were decided in fiscal year 2019, 6,620, or 87 percent, had their asylum claims denied, Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse reported.

Perhaps, Spector said, these rural residents could make some headway by arguing they aren’t simply fleeing criminals, but fleeing violence by what amounts to a state actor — the armed groups who run their hometowns.

The fact that Pacheco was a farmer who produced opium paste for the American drug market may not help his case. But he told me there’s nothing unusual about growing poppies in the Sierra, and his views are well-documented.

“I was a farmer. I was also a proponent in the Sierra region of legalizing drugs like poppies and marijuana. I broke the taboo,” he said.

Now he’s just another asylum seeker, trying to convince a skeptical set of immigration judges that his case fits the narrow criteria for receiving permission to stay in the States.

President sets aside humanitarian plank

On the issues of immigration and security, Mexico’s new president, who took office in December 2018, campaigned as a humanitarian.

Here’s how then-adviser Olga Sánchez Cordero put it during the campaign: “The policy priority of Andrés Manuel López Obrador will be that migrants’ rights are respected without restrictions. We want to be a country of refuge.”

Initially, López Obrador made good on that promise. His first appointed head of Mexico’s immigration agency, Tonatiuh Guillén, explained the policy to me this way in an interview in his Mexico City office:

“The project combined a strategy of, first, respect for human rights; second, inclusion within Mexico; and third, generating development in the south of Mexico and the north of Central America.

“That went along with other ideas, like, for example, it was a high priority to create a regional labor market between Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and southern Mexico.”

As immigration chief, Guillén was working for Sánchez Cordero, the adviser who became Mexico’s interior secretary.

But then President Trump threatened to close the border and to impose tariffs. Mexico’s Foreign Relations Ministry fought to accommodate Trump and clamp down on foreign migration, while the Interior Ministry fought to remain on the same humanitarian course.

Foreign Relations won — and in June Guillén was out of a job, less than eight months after starting as director of Mexico’s immigration agency.

President López Obrador’s harsher approach has become popular.

A January poll by El Financiero newspaper showed that 64 percent of Mexicans support a policy of closing the border to foreign migrants, as compared to 34 percent who want to support migrants and guarantee them free transit through the country.

The new policy’s results are still visible along the Guatemalan border in southern Chiapas. Immigration agents and members of the newly formed National Guard are deployed along the Suchiate River and at inland checkpoints.

At Ciudad Hidalgo, a city that has thrived for decades on informal cross-border commerce done in the open on rafts poled across the river, immigration agents now check the people who come across. It’s the first time in decades, and it’s upsetting local merchants because their customers across the river in Tecún Umán, Guatemala, have a harder time crossing to buy things in Mexico.

“We chiapanecos (people from Chiapas) are getting tired of being Trump’s wall,” former mayor Matilde Espinosa Toledo, of Suchiate county, told me. “Commerce is down by 30 percent.”

Informal crossings of the Rio Suchiate between Ciudad Hidalgo, Mexico and Tecun Uman, Guatemala.

“We have our own refugees”

The new displays of government authority that annoy some residents on Mexico’s southern border are what displaced people and some experts say is needed in Guerrero. This isn’t an ungovernable state, they say, but one that has slid over 20 years into rule by warlords.

Still, Mexico’s president has opposed any sort of confrontation with armed groups that might turn violent, trying to avoid the mistakes of former President Felipe Calderón, who unleashed an unproductive, bloody drug war in 2006-2012.

I pointed out to López Obrador that displaced residents I’ve interviewed want the government to take action that allows them back safely in their homes.

He responded, “If we unleash war, and if we carry out that war without caring about the number of dead ... we’re just going to generate more violence.”

A member of an invading “community force” wields an AK-47 after a battle for the village of Filo de Caballos in 2018. The federal government flexes its authority on Mexico’s southern border but has not come to terms with the violent displacements in Guerrero state.

In recent days, he went further, telling National Guard trainees in a videotaped visit: “We have to be respectful of human rights. Criminals are human beings, too, and deserve our respect.”

Popular opinion may support López Obrador’s crackdown on foreign migration, but his extreme caution and even respect toward criminal groups frustrates many, especially people forced from their homes.

The same El Financiero poll showed 56 percent of the Mexican public is dissatisfied with the president’s performance on public safety.

It’s past time to recognize Mexico’s own growing migration problem and act on it, said Guillén, the former immigration director.

New immigration inspections on Mexico’s southern border enjoy broad popular support, though some merchants complain.

“We have our own refugees. We need to clarify that, measure it, analyze it,” he said. “We have to focus all our efforts, using all our capacities in intelligence, in the security apparatus and in development, and stay there not just a little while. They have to be there two years, three years — not a little while.”

In Leonardo Bravo, Mayor Cástulo hasn’t seen any movement in that direction. He’s asked for federal intervention but got nothing more than sporadic financial help to pay for the rent and food of some displaced people.

“The federal government says they have to build a very good strategy, in which nobody is hurt and everything ends up in peace, and that’s going to take some more time,” Cástulo said. “We’re all in touch, and the day this is worked out, worked out for everybody, we’ll all head back to the Sierra.”

What southern Mexico’s migrants most want isn’t rent subsidies, or food assistance, or a form letter that might help them win asylum in the United States.

They want the government to take action, like it did on the southern border, so they can live in peace in their own homes.

Family haunted by fear after fleeing Guerrero for border at Nogales

By Tim Steller, Arizona Daily Star

NOGALES, SONORA ─ When migrants fleeing violence arrive at the border in Mexico, they haven’t really escaped and continue to feel a gnawing fear.

This has come across to me in interviews with Mexicans and Central Americans in Tijuana and Mexicali but really struck home with a family from Guerrero whom I met in Nogales, Sonora.

The family, whom I’m not naming for their protection, had lived in their hometown in rural Chilpancingo county for generations. But then June arrived, and the wind changed direction in their town — a new criminal group moved in, they told me.

The 39-year-old mother in the family has 11 siblings, most of whom lived in their hometown. But her three brothers, metalworkers, would not agree to work with the new criminal group or pay them protection money, she said.

“They said that since they weren’t involved in anything, since they were working cleanly, they had no reason to run away from the village,” the mother said.

In late June, three of them were killed, two of them taken from her house while her family watched. After police found the bodies strewn on a roadside, the extended family buried the men quickly and arranged with one another to leave the next day, the father said.

Thirty-six family members fled, many of them walking eight hours through the mountains to avoid criminals’ checkpoints on the roads. They left seven houses empty in their hometown.

The extended family stuck together initially, as they went to Mexico City and Hermosillo, but eventually split up as some members went to the northern cities of Agua Prieta, Sonora; Janos, Chihuahua; Tijuana, Baja California; and Nogales, Sonora, where I met nine family members.

There they have been waiting for months for their number to come up in the “metering” system that decides when asylum seekers can have an appointment with U.S. Customs and Border Protection. They pass their nights in a shelter and their days at a Mexican migration agency office and the Kino Border Initiative’s dining hall.

But like many asylum seekers I’ve met, they’re stalked by fear, in part of local criminals but mostly of other people from the area where they’re from. They have seen some of them in Nogales and worry that all it would take for their own family to be targeted is a phone call.

“We’re afraid of them because they want to disappear the family,” the mother said. “They don’t want anybody who can get in their way.”

A yearlong project

This is the first column in a project by Arizona Daily Star columnist Tim Steller about how government actors in the U.S. and other countries try to mold public opinion about immigration and the U.S.-Mexico border. It is funded by a fellowship from the Society of Professional Journalists Foundation. The Star will publish the columns periodically over the next year.