PHOENIX — In a legal epic worthy of comic-book treatment, a Tucson attorney has lost a key battle with Marvel Comics over the patent royalties for a Spider-Man web blaster he developed.

In a 6-3 ruling Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected arguments by Stephen Kimble that his agreement with Marvel for ongoing royalties on the toy he developed should overrule a 51-year-old precedent about when patents expire. Justice Elena Kagan, writing for the majority, said the right of free access by the public to ideas trumps such agreements.

“Patents endow their holders with certain superpowers, but only for a limited time,” Kagan wrote. Kagan said Congress designed patent laws, including the 20-year limit — to strike “a balance between fostering innovation and ensuring public access to discoveries.”

More to the point, she and the majority were not willing to overturn a 1964 high court ruling in a similar case which said that “free access” to ideas trumps any other agreement.

That blind obedience to stare decisis — the legal concept of decided precedent — drew derision by Justice Samuel Alito.

“The decision interferes with the ability of parties to negotiate licensing agreement that reflect the true value of the patent, and it disrupts contractual expectations,” he wrote on behalf of himself and Justices John Roberts and Clarence Thomas. “Stare decisis does not require us to retain this baseless and damaging precedent.”

“What we can decide, we can undecide,” Kagan acknowledged. But she cited a quote from a 1962 Spider-Man comic to justify not using that authority here: In this world, with great power there must also come great responsibility.

Kimble told Capitol Media Services that the battle with the comic book giant going back two decades continues despite Monday’s ruling, with another case pending in federal court in Tucson.

“I had a kid who was not a real big fan of reading,” Kimble said of the genesis of the idea. But the child, Kane, loved Spider-Man comics and the two read them together before bed.

That led to a discussion of whether Kimble could come up with a toy that would allow a child to play at Spider-Man.

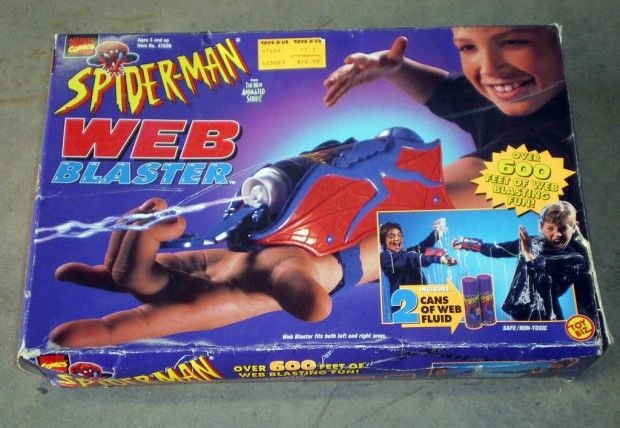

The toy has a trigger attached to a valve in the palm of the glove. That valve is attached to a flexible line leading to a can of foam that could be strapped to the user’s wrist or waist. Press the trigger and a string of foam shot out.

After having it patented, Kimble met with an executive of Toy Biz Inc., the company that had the right to market Marvel toys, to pitch the idea.

Kimble said the executive told him Marvel would compensate him if it ever decided to use any of his ideas. But the company later said it was not interested.

In 1995, however, Marvel began manufacturing a similar toy called the “Web Blaster,” contending it had come up with the idea independently. Kimble subsequently sued.

A federal judge threw out a claim of patent infringement. But a jury concluded Marvel had breached an oral contract with Kimble, awarding him 3.5 percent of past, present and future product sales.

In 2002 they settled the case out of court, with Marvel purchasing Kimble’s patent, providing $516,000 immediately and 3 percent of sales that would infringe on the patent. He eventually collected about $6 million before a subsequent squabble over royalties on variations of the toy brought the case back to federal court.

That resulted in a trial judge ruling that the deal Kimble signed included his patent rights. With the 20-year limit on patents, that meant the royalties had to end when the patent expired.

In arguments to the justices, Kimble acknowledged their 1964 ruling which affirmed that 20-year limit on patent royalties. But he asked they overturn the precedent in favor of “flexible, case-by-case analysis” in cases of royalties beyond the 20 years.

The justices refused.

“Respecting stare decisis means sticking to some wrong decisions,” Kagan conceded. She also noted that if Congress believed that 1964 decision was wrong it has had multiple opportunities to amend the law, something it has not done.

Kimble, however, is not done yet.

He said Monday’s ruling deals only with the question of the patent that Marvel bought as part of that 2002 settlement. But Kimble said Marvel made separate verbal promises it would work with him.

For example, he said Marvel officials told him they like his idea and will “work something out.” And those promises, he said, are legally separate from the patent itself.

“The patent is now gone,” he said of Monday’s ruling. “But the promise still exists.”

Kimble also took a slap at Kagan and the majority for giving so much weight to that 1964 ruling.

“The one thing that really stinks in my mind is (the court saying that) it’s more important that the rule (of law) be settled than it be settled right,” he complained.

Kagan does use that verbiage. But it’s not original, actually having been written by Justice Louis Brandeis in a 1932 decision.