Imagine if your favorite food could bite you back while you eat it.

That’s what horned lizards face each time they scarf up harvester ants armed with powerful mandibles and a toxic sting.

Luckily, evolution has equipped the reptiles with an array of skills and defenses to make meal time as painless as possible.

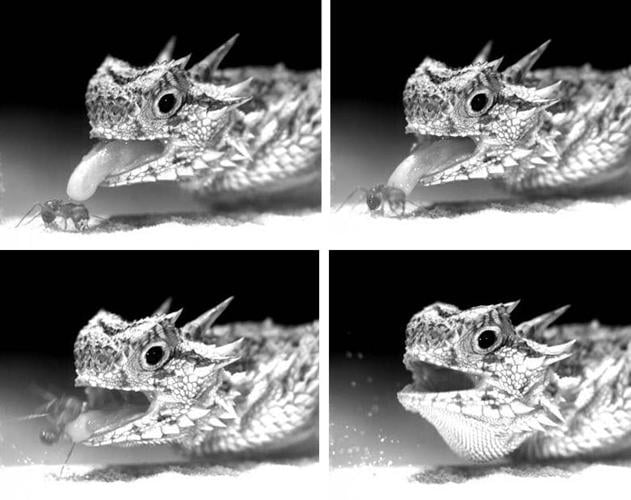

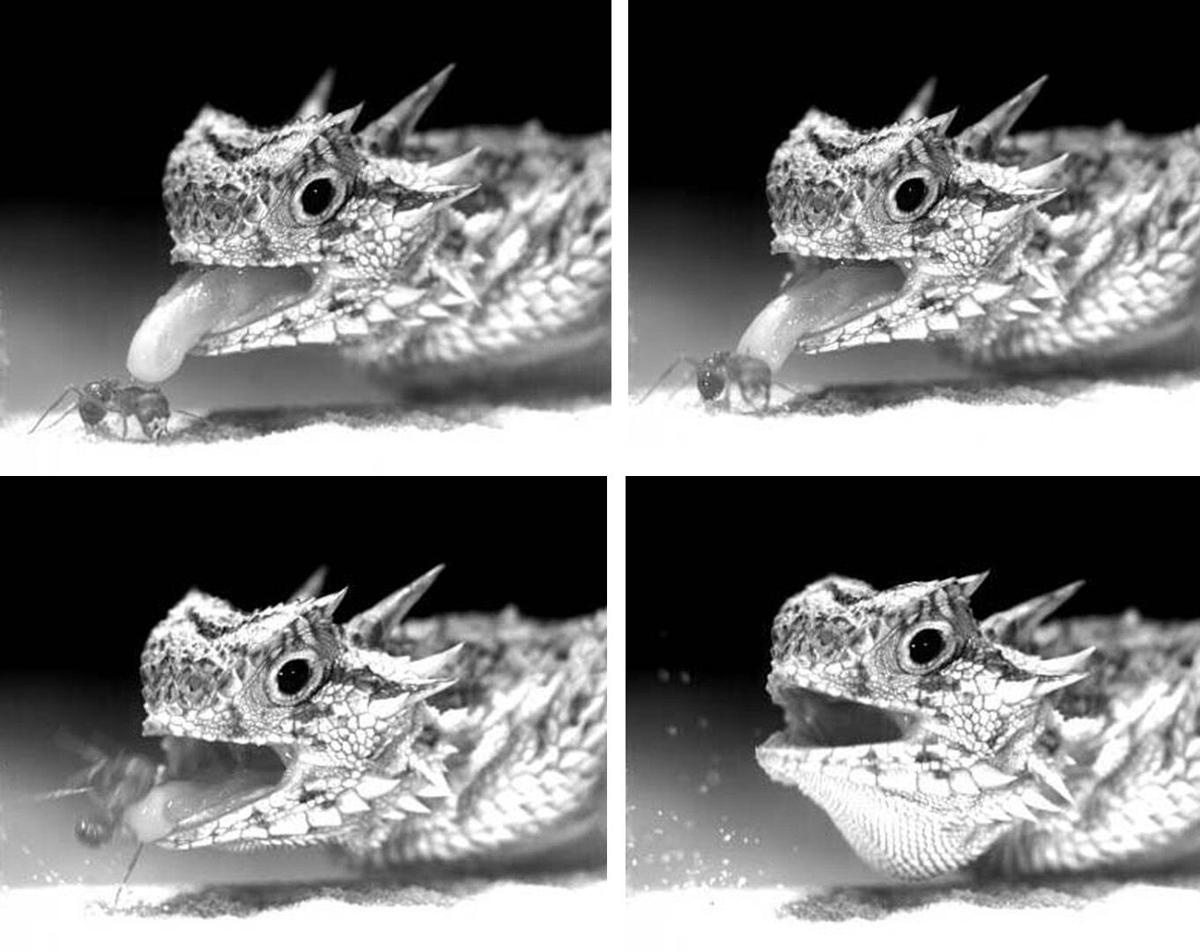

Using ultra-high-speed photography, an international team of researchers led by Tucson-based expert Wade Sherbrooke has documented the horny toad’s almost-surgical feeding technique like never before.

Super-slow-motion footage from a high-speed camera shows the precise and careful way that horned lizards eat harvester ants to avoid the insects' powerful bite and toxic sting. The footage is part of a study recently published in the scientific journal Biology Open.

With a precise flick of its tongue, the horned lizard strikes the ant on its back just behind its head and lifts the insect so its legs, stinger and pinchers are pointing harmlessly at the sky.

“The ant can only bend its head and its abdomen down, so how you pick it up is pretty important,” Sherbrooke explained. “They’ve got it down just right.”

There is no chewing involved. The ant is swallowed headfirst and whole after being pushed through a curtain of mucus at the back of the lizard’s mouth to immobilize it during its short trip to the stomach.

The strike unfolds in less than half a second. “You see it happen, but you don’t really see it,” Sherbrooke said.

The fastest part, from the moment the lizard’s tongue makes contact to when the ant disappears down its throat, lasts just 60 milliseconds or about half as long as it takes a person to blink.

Since the human eye can’t process movement that fast, Sherbrooke said, eight Texas horned lizards and a batch of harvester ants were collected in southwestern New Mexico and shipped to the University of Bonn in Germany to be filmed with a camera capable of capturing up to 2,000 frames per second.

The feeding footage was then slowed down by a factor of 100, revealing in never-before-seen detail just how accurate the horned lizards are with their tongues, even when they are aiming at a particular spot on a moving target.

Super-slow-motion footage from a high-speed camera shows the precise and careful way that horned lizards eat harvester ants to avoid the insects' powerful bite and toxic sting. The footage is part of a study recently published in the scientific journal Biology Open.

“This photography is really incredible,” said Sherbrooke, director emeritus of the American Museum of Natural History’s Southwest Research Station in the Chiricahua Mountains, 160 miles southeast of Tucson.

He said the new imagery highlights the intricate ways evolution has enabled horned lizards to feed on “an abundant prey item that’s very well defended.”

Even when horned lizards do get stung by harvester ants, their blood has adapted a way of blunting the effects of the venom, which is considered among the most toxic in the insect world.

“If you’ve ever been stung, it’s a memorable experience,” Sherbrooke said.

He co-authored the study with European scientists Ismene Fertschai, Matthias Ott and Boris Chagnaud. Their findings were published last month in the journal Biology Open.

Sherbrooke is perhaps the world’s leading expert on horny toads, with more than 60 published papers on the reptiles. He literally wrote the book on them. His “Introduction to Horned Lizards of North America” was originally published in 2003.

He said he decided to study horned lizards 45 years ago because not much was known about them at the time.

With the flick of its tongue, a horned lizard strikes a harvester ant on the back of the head and lifts the insect so its pointing harmlessly at the sky.

“It wasn’t the money,” he said with a laugh. “The only grant I ever got was from the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum the first year I was studying them, and that was for $200.”

The Texas variety is the largest and most widely distributed species of horny toad in North America. Sherbrooke said they can be found across southeastern Arizona as far west as Benson, while the ones generally seen in the Tucson area are regal horned lizards.

“They’re part of our landscape,” at least for now, he said. Sightings in Tucson have fallen dramatically in recent decades due to habitat loss and the widespread use of pesticides to kill off their primary source of food.

“The more we eliminate ants, the more we eliminate horned lizards,” he said.

Sherbrooke is already making plans to build on the high-speed camera research by examining the effect of horny toad mucus on a defensive pheromone harvest ants release when they are in danger.

By striking quickly and coating their prey in goo, the lizards could delay or prevent an ant from sending out that chemical signal and triggering a painful counterattack by the rest of the ant colony. That would allow the reptiles to stay put and continue feeding, safe from the mob.

Sherbrooke said it’s something he and his fellow researchers speculate about in their new paper but can’t yet prove. He aims to test the idea this summer.

“One thing about science is every time you learn something, new questions pop up that you never even thought of,” he said.

Southern Arizona wildlife photos that will make your skin crawl

Southern Arizona snakes

UpdatedWe've got a crazy #WildlifeWednesday post for you!

— Arizona Game & Fish (@azgfd) May 15, 2019

Check out this Sidewinder eating a very large Desert Iguana out by Picacho Peak! 🤯

Video by Randy Babb#snake #southwest pic.twitter.com/13TkOxtOmv

Southern Arizona snakes

Updated

This rattlesnake seemed to be having trouble consuming this lizard, but after a brief period, consumed the whole thing.

Southern Arizona snakes

Updated

Western Diamondback Rattlesnake caught a Mouning Dove napping, and the rest of the story was.......lunch.

Southern Arizona snakes

Updated

Just watch out for ... snakes!!!

Southern Arizona snakes

Updated

A tiny baby snake the size of a quarter

Southern Arizona snakes

Updated

We have a King Snake living in our backyard. Bonus - No rats, no rabbits, no squirrels - and no rattlesnakes!

Southern Arizona snakes

Updated

NOT a welcome visitor to our front porch...

Southern Arizona snakes

Updated

A rare sighting in Tucson: a king snake killing a rattlesnake by constricting it.

Southern Arizona snakes

Updated

This snake began a slow, slithering ascent from the base of a natural stone arch along the Catalina Highway northeast of Tucson. It’s very unlikely the critter got very high on the formation.

Southern Arizona snakes

Updated

Southern Arizona snakes

Updated

Southern Arizona tarantulas

Updated

Schmidt shows off a female tarantula that is part of the insect collection he keeps in his office.

Southern Arizona tarantulas

Updated

An Avicularia spider crawls up the side of a glass container at the "Spider Mall" during the American Tarantula Society's annual conference in Oro Valley, Ariz. on Friday, July 29, 2016. The Avicularia is just one of the many species of tarantulas present at the conference.

Southern Arizona scorpions

Updated

Lizard captures scorpion for lunch

Southern Arizona centipedes

Updated

Giant centipedes will be on display at the Insect Festival.

Southern Arizona snakes

Updated

Saw it in backyard while gardening after rains. Really blended in with gravel! Did hear it “rattle”before it went into hole under boulder.