Pima County’s supervisors voted for the first time to reject federal money that encourages collaboration between the Sheriff’s Department and the Border Patrol, citing Trump administration changes in immigration enforcement.

On a 3-2 vote along party lines, the Board of Supervisors rejected a more than $1 million Operation Stonegarden grant. The grant is meant to help agencies along the border pay overtime and buy equipment to coordinate efforts with federal agencies to improve border security.

Voting to reject the grant were Democrats Richard Elías, Sharon Bronson and Ramón Valadez; Republicans Steve Christy and Ally Miller dissented.

“It’s a new deal out there at the border and the board is concerned with having our sheriffs become more involved in working on federal immigration law,” said Elías. “Frankly, we have a different administration in the White House and we’ve seen a lot of change in the way ICE and the Border Patrol do business here in the borderlands.”

The county has received Stonegarden funds for more than a decade. It is believed this is the first time the money has been declined in Arizona, according to Sheriff’s Department officials and an Arizona Department of Homeland Security spokeswoman.

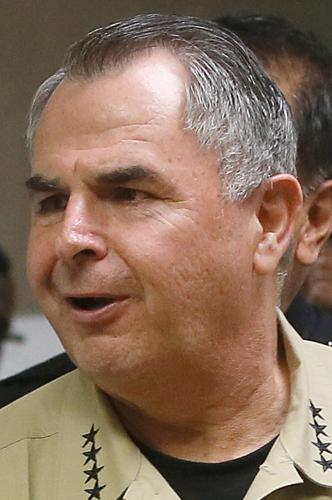

Sheriff Mark Napier said he was very disappointed in the decision.

“The funds are directed at the interdiction of drug and human trafficking organizations in Pima County and it allows us to work more effectively with our federal partners,” which contributes to public safety in the county, he said.

The department was set to receive $1.19 million for mileage and overtime and close to $238,000 for satellite data equipment and a wireless transmission device. In fiscal 2017, the four border counties in Arizona were awarded $11.8 million.

During the board meeting Tuesday, Elías said the equipment often bought with these grants contributes to further militarization of the border.

“I definitely want them to have the tools they need, but there’s a limit to it,” he said later.

In response to Bronson’s concerns about the overtime pay, County Administrator Chuck Huckelberry said every dollar of overtime requires the county to pay an additional 67 cents into the state retirement fund on behalf of a deputy.

But if paying more overtime was a concern, “why have they been accepting the grant?” asked Christy, who said he was surprised by the vote.

“The Sheriff Department has come to rely on this grant, based on past acceptance, and suddenly it’s determined by the board it is no longer going to be accepted,” he said.

“It strains the Sheriff’s Department ability to effectively conduct law enforcement in our country,” and jeopardizes public safety in terms of drug smuggling, human trafficking and illegal immigration, Christy said.

From fiscal 2008 through 2016, the federal government has allocated about $59 million annually, or $531.5 million in total, for Stonegarden, according to a November 2017 Office of Inspector General report on the program. But the idea behind it is to supplement existing state funds, not replace them.

Over the years, there have been allegations of fraud and waste, with some states receiving overtime money for things unrelated to border security. The OIG report found that neither Customs and Border Protection nor the Federal Emergency Management Agency, which oversee the program, were meeting oversight responsibilities to monitor grantees or show how the grant was contributing to its goals.

A 2009 investigation by the Arizona Daily Star analyzed how 10 Arizona agencies had used $7.3 million, and found that the program was loosely monitored, had no clear objective and no benchmarks for success.

In instances, in addition to targeting organized criminals, funding was used to pay for an officer’s time issuing traffic citations or for controlling crowds. A Bisbee deputy police officer worked an average of nearly 80 hours a week between regular and overtime hours, earning $131,000 from 2007 to mid-2009 working on border-security overtime Stonegarden shifts.

But the additional money allows deputies to do things they otherwise wouldn’t be able to on regular duty time, Napier said.

Pima County shares 125 miles with Mexico and parts of it fall under one of the busiest drug trafficking corridors, the Republican sheriff said.

In response to concerns about deputies being tasked with enforcing immigration laws, Napier said: “ My department is not interested in proactively enforcing federal immigration laws; it is not our responsibility and we don’t have the resources to do so.”

While his department has about 500 sworn officers, the Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector has nearly 3,700 agents.

This doesn’t mean his department doesn’t cooperate with federal authorities.

“When we become aware that there’s a violation of federal immigration law, we notify federal authorities, as people should expect us to do,” Napier said.

Unlike other local law enforcement agencies in Arizona, the Sheriff’s Department does not have a specific policy or guidelines as to how deputies have to document calls to Border Patrol nor a uniform way to track those interactions.

Napier told the Star his department will look into creating a log to track its requests for Border Patrol assistance that can be queried beginning March 1.