PHOENIX — A measure to boost taxes on Arizona’s most wealthy can’t go on the November ballot because the description of the measure fails to inform voters of what it really does, a judge ruled late Friday.

In a 20-page order, Maricopa County Superior Court Judge Christopher Coury laid out what he concluded are both misleading statements and full-blown omissions in the legally required 100-word description that is placed on the petitions. Any one of these, he said, would have been enough to disqualify the initiative, which sought to raise $940 million a year for K-12 education.

And taken together, Coury said, the description creates “the substantial risk of confusion for a reasonable Arizona voter.”

“Invest in Education circulated an opaque ‘Trojan horse’ of a 100-word description, concealing principal provisions of the initiative,” the judge wrote.

“No matter how well-intentioned Invest in Education’s initiative was, its nontransparent description violates Arizona law,” he continued. “Consequently, this self-inflicted shortcoming will prevent voters from considering this initiative — a result that understandably will disappoint and trouble teachers, administrators, some education advocates, and many Arizona voters.”

Joe Thomas, president of the Arizona Education Association, one of the groups backing the measure, called the ruling “bizarre,” “shameful” and “political.” He said that initiative backers turned in petitions with more than 435,000 signatures.

“Instead of respecting the voters, Judge Coury inserted his own political views throughout his baseless ruling,” he said in a prepared statement.

Friday’s ruling is not going to be the last word. Backers of the Invest in Education measure are going to seek review by the Arizona Supreme Court.

But Coury, likely anticipating such a move, said he doubts that would be successful.

He pointed out that the justices threw out a similar measure backed by the same group two years ago, also over the adequacy of the description of the proposed change in tax rates. But Coury said the backers did not learn their lesson.

“Instead of using the phrasing that had been blessed by the Arizona Supreme Court, Invest in Education chose to use different language, as was its right,” he said. But Coury said initiative backers have no one but themselves to blame for ignoring that 2018 ruling.

“When a teacher specifically instructs a student exactly how to complete a math problem, and when the student disregards the instruction and does the math problem incorrectly on a future test, should the student receive a passing grade,” Coury wrote. “The simple answer is no.”

Initiative backers seek to raise $940 million a year for K-12 education by imposing a 3.5% income tax “surcharge” on earnings exceeding $250,000 a year for individuals and $500,000 for married couples filing jointly.

It was that description as a “surcharge,” the judge said, that became a key mistake.

He said some voters might understand that would add 3.5 percentage points on the current top state income tax rate of 4.5%. But others, Coury said, might interpret it to be a temporary tax, or even just a 3.5% increase in taxes when, in fact, the taxes owed on earnings above that point would increase by 77.7%.

The judge also said the description fails to inform voters of the initiative’s impact on the owners of certain businesses who pay individual income taxes versus corporate taxes.

And then there is what Coury said is the failure to explain in the description how the cash raised would be distributed, including that half would go to “teachers, classroom support personnel and student support services personnel.”

“To some reasonable voters, devoting 50% of the money generated by the initiative directly to teacher salaries may have sounded too rich; to other reasonable voters, devoting 50% of the money raised directly to teacher salaries may have sounded too modest,” the judge wrote. “The failure to disclose the distribution in the 100-word description constitutes the omission of a principal provision.”

Coury also said that, given the definition of “teacher” in the actual measure, “it is highly likely that less than 50% of the money raised by this proposed ‘surcharge’ would end up in the salaries of actual classroom teachers as they are commonly understood in the common vernacular.”

He also said the description failed to explain how the measure would tie the hands of Arizona lawmakers, forbidding them from reducing other funding for public education once these new funds started to flow.

Coury brushed aside the fact that each petition had an actual copy of the initiative attached, meaning that would-be signers with questions could have actually read the entire document if they had questions.

He said that those who would choose to go beyond the petition and the 100-word description would first have seen the “finding and declaration of purpose” section of the measure. And that verbiage, the judge said, only “magnifies the significant risk of confusion” of failing to mention key provisions in the description.

Anyway, Coury said the Supreme Court itself, in its 2018 ruling knocking the earlier version off the ballot, specifically rejected the argument that a confusing 100-word description is permissible simply “because the truth may be discovered in the many pages of the initiative.”

This isn’t the only lawsuit this year seeking to disqualify measures from the ballot based on the adequacy of the description.

Separate action has been filed along the same lines by foes of legalizing recreational use of marijuana by adults, giving judges more discretion in sentencing, and a package of health-related measures that includes a 20% pay increase for hospital workers. Hearings on those begin later in August.

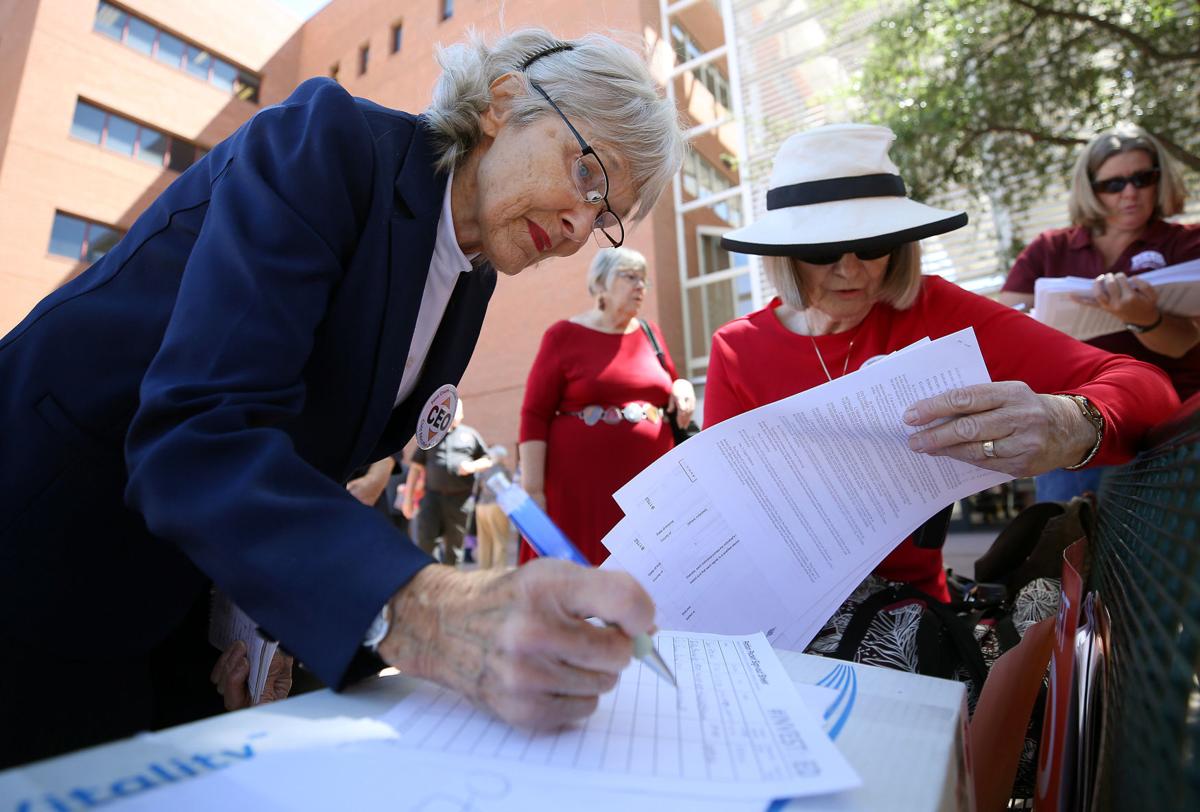

About 200 gathered at Congress and Grande to commemorate last year's RedForEd protests and Arizona-wide teacher walk out, Tucson, Ariz.