Six years ago, David Schaller tried to make a difference in the climate and his native city’s quality of life.

After a career at the EPA, Schaller was lead author of a $48,000 blueprint commissioned by Tucson for tackling climate change by reducing emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

The report’s most ambitious recommendations for laws and incentives never became reality. Instead, economics and politics dictated a voluntary strategy. But many of the voluntary measures weren’t fully carried out, although the city has taken some steps toward reducing energy use.

The agenda laid out in 2011 by consulting firm Westmoreland Associates, which Schaller founded, went a lot farther:

- Mandatory “cool roofs” in new homes to reduce their solar heat intake.

- Limits on how long vehicles can idle in parking lots, burning fossil fuels.

- Mandatory energy efficiency retrofits of homes and apartments when they’re sold.

- Rebates for buyers of electric vehicles, and of new homes with Energy Star-rated appliances.

These and 30 other recommendations filled Westmoreland’s highly detailed 360-page report to the city’s advisory Climate Change Committee.

The committee sliced out virtually all measures costing tax money and most that proposed regulations — “out of a belief they were too radical and would not fly,” recalled Ron Proctor, a former committee member associated with the group Sustainable Tucson.

The committee published and the City Council approved a report recommending more than 20 mostly voluntary measures. But many of those actions were cut short by city and federal budget cuts.

Now, with brutal summer heat beating down on Tucson, city officials are about to give the climate issue a second look. Mayor Jonathan Rothschild, who took office less than a year after Schaller’s report appeared, is spearheading the effort that will include public hearings.

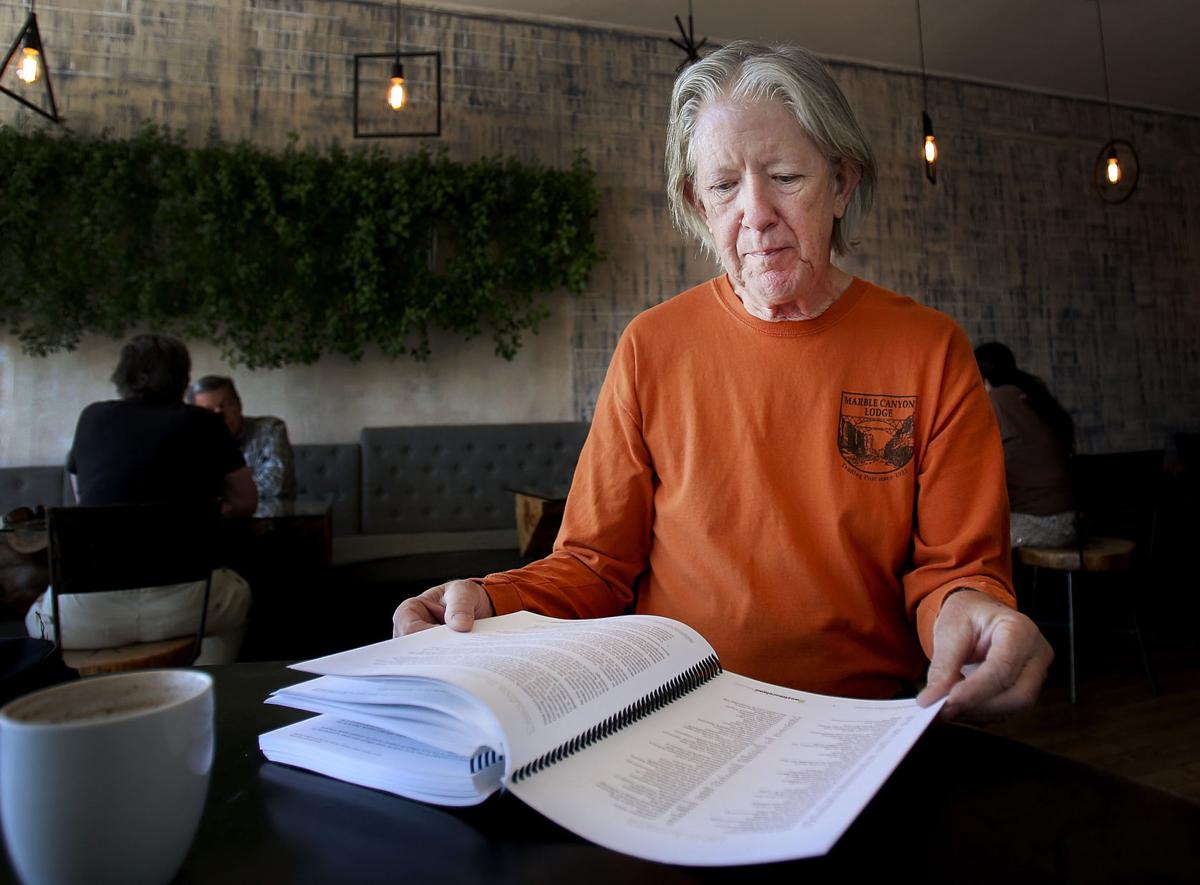

But Schaller describes himself as “beyond frustrated,” disheartened and disappointed at his report’s inability to gain traction back then.

“It’s been a missed opportunity,” he said. “We lost six years. The fact that they are now talking about revitalizing things is a bit of admission there has been momentum lost.”

Several climate committee members said many of the report’s recommendations were unfeasible. But they were very disappointed that more wasn’t done on even the voluntary measures.

Their experience shows how hard it is for cities — or any governments — to take on something as big as climate change.

A decade of effort

Tucson efforts to combat global warming date to 2006, when the City Council signed the Mayors’ Climate Protection Agreement. Organized by the U.S. Conference of Mayors, the pact committed more than 1,000 U.S. cities to reduce greenhouse gases 7 percent from 1990 levels by 2012.

Schaller arrived a year later, hired by the city as a sustainable development administrator after working 28 years for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, ending his tenure at a similar post in Denver. A native of Menlo Park on Tucson’s west side, he was a Salpointe High School graduate who obtained a bachelor’s degree in geology and a master’s in environmental policy from the University of Arizona in the 1970s.

He worked with the city’s Climate Change Committee until early 2010, when he was laid off during the economic slump. In October 2010, the city awarded Westmoreland Associates the climate report contract after competitive bidding.

Westmoreland calculated how much each measure would reduce greenhouse gas emissions, would cost in the short term and would reap in long-term benefits. It combed the internet to show that each measure had been used by at least one government entity in other states.

The report concluded that not only would the economic benefits ultimately outpace costs, they would produce unrelated benefits:

- Upgrading homes’ energy efficiency would make them cooler and more comfortable and raise their resale value.

- Replacing conventional intersections with traffic circles known as roundabouts would reduce accidents, injuries, fatalities and city emergency response costs

- .

- Limiting vehicle idling “not only saves thousands of gallons of gasoline and diesel fuel daily but would also improve local air quality, reduce noise, enhance vehicle engine life, and improve overall community well-being.”

These measures would take Tucson halfway to its 7 percent greenhouse gas reduction goal — by 2020, the report concluded.

“We would have a quieter, healthier community” with these recommendations, Schaller said. “If all sustainability is local, this would have been a chance to do it.”

Too ambitious?

But climate committee member and transportation consultant Curtis Lueck said he quit the committee after a few meetings, feeling that many of the report’s strategies “seemed ill-conceived, draconian, and impossible to fund at the time.”

“The committee was trying to do too much. ... That made it difficult to look at things in more detail and figure out which ones had biggest bang for the buck,” he said.

Requiring retrofitting of all homes and apartment buildings when sold — “what was the chance, politically, of that proposal?” added John Schwarz, a former committee member and a retired University of Arizona political science professor. “There are huge economic implications of that kind of proposal.”

Even if the measures paid off after a few years, “who will put up the money up front and are the winners the same as the losers?” Schwarz asked. “There were a whole bunch of questions like that. We were not equipped ... to figure out that stuff.”

One proposal ranking high on the greenhouse gas reduction scorecard was voluntary — having 10 percent of the city’s drivers buy carbon “offsets.” Drivers would pay others to plant trees, buy solar water heaters or start a bike sharing program.

Westmoreland’s report noted the president of the Pew Center on Global Climate Change said, “Offsets are crucial to achieving emissions reductions targets.”

But Leslie Ethen, former head of the city Office of Conservation and Sustainability, said she doubts that offsets have happened here “to any considerable extent.”

“It’s something we don’t track” due to lack of resources, said Ethen, now planning and sustainability manager in the city’s Planning and Development Services Department.

The climate committee also recommended several voluntary “climate challenges” for residents and businesses. The city staff would start educational programs to explain renewable energy and energy efficiency’s benefits. Goals were set for how many energy-saving devices would be installed by 2020.

The programs were started and some continued for years. But Ethen said the city doesn’t know how many people or businesses participated because it lacks personnel to monitor them.

In 2011, the Office of Conservation and Sustainability had eight staffers, but tightening city budgets later wiped out all positions. The department was ultimately eliminated, although Ethen said at least some of its work is done by other agencies.

Many of its programs — including Schaller’s study — were financed by federal grants including the Obama administration’s 2009 stimulus bill that eventually ran out, Ethen said. With the strapped city budget, City Hall has had to focus on its and the public’s top priorities — improving roads and public safety, she said.

The climate committee’s report “is great and helpful to our community. But it’s not as core a function as paving roads,” Ethen said.

Ethen says the city has made some climate inroads, including recently introducing “performance contracting” to borrow money for energy-saving projects, with savings from lower energy costs repaying the loans. That’s how it could install low-energy, LED streetlights citywide, and that’s how it will start in about six months on a $15 million project to install renewable and energy efficiency projects in two city recreation centers and City Hall.

Transit service also has improved, higher-density, transit-friendly development in the urban core is outrunning building on the city’s periphery and $9 million worth of bicycle “boulevards” where cycles are given more room than usual are in the works, city staffers said. A city bike-sharing program — recommended in Schaller’s report — starts at the end of 2017.

While Schaller’s roundabout push went nowhere, Lueck says the city’s Michigan left turn intersections on Grant Road “are essentially elongated roundabouts in function.”

Commitment needed

Lueck and former climate committee member Phil Swaim say many of the Westmoreland report’s recommendations could still be adopted today, although they’d prefer using incentives to coax people and businesses to save energy instead of regulations.

“It takes community will and political will,” said architect Swaim, adding, “a 116-degree day is a good reminder — it gets people’s attention.”

Rothschild was noncommittal about the report, saying he needs to review it again. Some measures are “a bit dated” due to technology changes, while many people are carrying out some of its proposed mandates such as cool roofs on their own, he said.

As for regulations, the mayor pointed to the state Legislature as the problem, saying it has halted city efforts to regulate climate issues in the past. “We need to be more creative in our approach than relying on mandates,” he said.

Schaller, now retired, said he hopes that this time, the city makes sure that what’s approved gets done.

“It won’t happen without somebody taking ownership and assigning responsibility ... things don’t happen by themselves.”