Witnesses from Arizona giving testimony Wednesday at a U.S. Senate committee hearing on border management categorized the situation at the U.S.-Mexico border as a crisis.

They included Yuma Mayor Douglas Nicholls, Sierra Vista Mayor Clea McCaa II, and Pima County Deputy County Administrator and Chief Medical Officer Francisco Garcia.

“A hundred-and-fifty-thousand asylum seekers processed in Pima County from 2019 to the present — yes, this is a crisis,” Pima County’s Garcia said at the hearing. “It is using up resources that we need to use for other purposes, even with the federal support.”

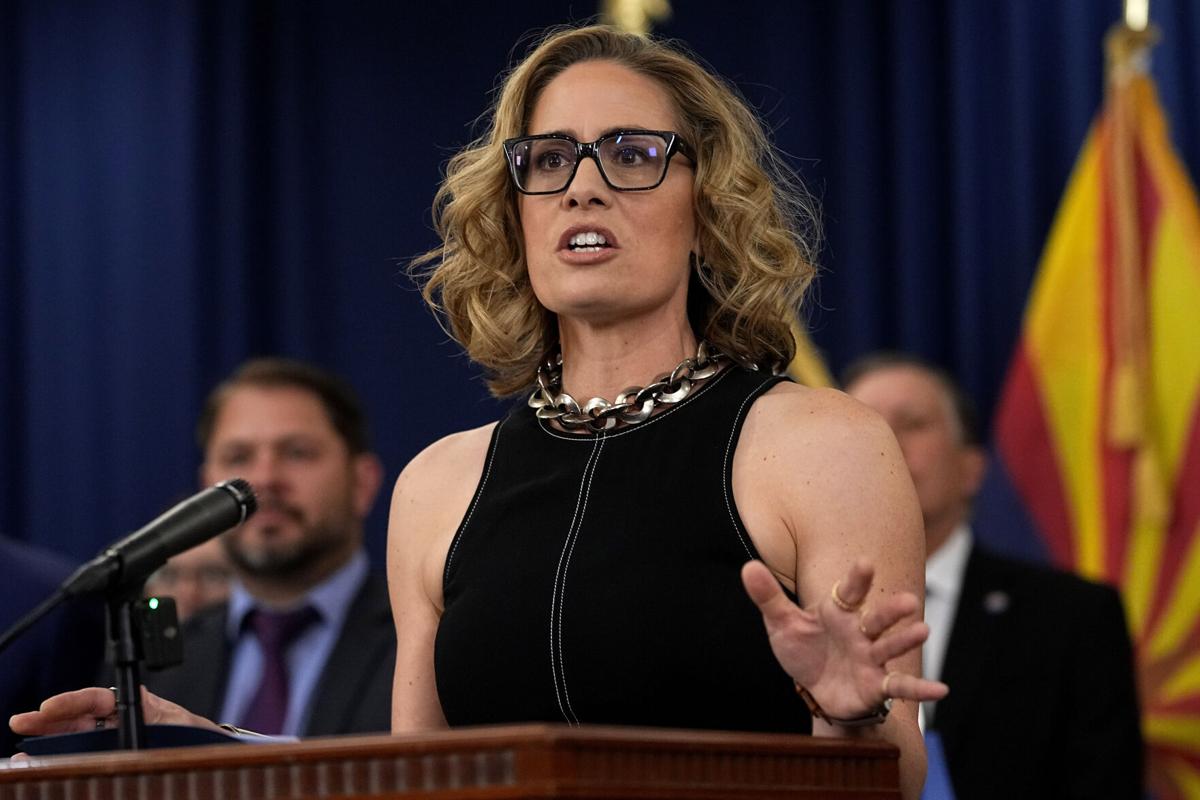

U.S. Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, I-Arizona, and other members of a Senate committee held the hearing in Washington, D.C.

The topics discussed included the increase of migrants who need services in local communities, the effects of increased human smuggling and high-speed pursuits, and possible upcoming effects of the end of public health policy Title 42.

Title 42 allows the U.S. government to immediately expel some migrants from the country. The Centers for Disease Control began the order as a pandemic control measure in March 2020, and it is set to end on May 11.

Migrants have been expelled under Title 42 more than 2.8 million times since it took effect. Many observers are concerned that the number of undocumented migrants entering the country will increase and might become unmanageable when the policy ends. Opponents of the policy say it subverts domestic and international asylum laws that say people fleeing specific types of persecution have a right to seek asylum.

Pima County has spent more than $23 million on migrant services since summer of 2019, which is being covered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Emergency Food and Shelter Program.

A recent federal spending bill included about $800 million for the FEMA program to go nationwide to cities and jurisdictions providing migrant services. Pima County has received a grant award for April and June and will continue to seek funds.

The more than $1 billion in funding Congress has allotted for migrant services is meant “to help ease the financial burden on nonprofits and local communities who are providing food, shelter and other services to migrants to ensure that the migrant crisis does not become a homelessness crisis,” Sinema said at the hearing.

‘The masking of a crisis’

Through 2022, the average number of migrants coming through Pima County daily and using services ranged from 224 to 770. The Border Patrol estimates when Title 42 ends, the county could receive up to 1,200 to 1,500 people per day, which would overwhelm existing local capacity without significant federal support, according to an April 4 memo from County Administrator Jan Lesher.

“The net effect of our efforts has been the masking of a crisis,” Garcia said in the hearing. “Few in Tucson, Pima County or Arizona know that federal entities are dropping off hundreds of people each day to local, county-supported shelter operations. … Pima County doesn’t want to be, nor should it be, in the business of sheltering and caring for people seeking asylum in the U.S. That should be the function of the federal government.”

The current funding strategy from FEMA doesn’t allow the county to plan more than three months at a time, Garcia said. The county needs funding that lasts for a longer time as well as more reliable reimbursements, he said, in the absence of Congress enacting comprehensive immigration reform or the federal government taking charge of the migrant services now being handled by local communities.

Nicholls, the Yuma mayor, wants the federal government to bring more resources to the border ahead of Title 42 ending, including ambulances, containers with food and supplies, medical supplies, medical professionals, mobile shelters and buses. And, like Garcia, he said it should take charge of much of the migrant services.

“Sheltering operations, I believe, really need to be taken over by actual FEMA activities and/or the National Guard,” Nicholls said. “Funding is important, but there are limits to organizations and we need to recognize that.

He also told the committee he wants to see increased diplomacy with Mexico about undocumented migration and a reimplementation of Operation Streamline, a controversial practice that federal courts previously used to quickly move migrants through deportation proceedings.

Impact beyond public view

Yuma has seen a large influx in migrants over the last couple of years. The Border Patrol’s Yuma Sector apprehended migrants at the border between 300 and 1,000 times a month in fiscal year 2020 and between 21,000 and 31,000 times a month in 2022. Those numbers have come down to an average of about 11,000 monthly since January.

When numbers peaked in 2021, Nicholls proclaimed a local emergency. In December of 2022, there were similar volumes of people and Yuma County cities San Luis and Somerton also made emergency declarations, he said.

“I want to stress the migrant crisis has negatively impacted Yuma far beyond what might meet the public eye,” he told the committee.

He said Yuma’s agricultural industry is affected by migrants entering fields of crops; the economic growth of Yuma is compromised by concern from possible investors about the changing border situation; and the regional medical center had a dramatic increase in migrant patients for emergency care, intensive care and maternity care, resulting in $26 million in costs.

McCaa, the Sierra Vista mayor, told the committee the biggest border-related issue facing Sierra Vista is roads made dangerous by human smuggling and high-speed pursuits.

Transnational organizations hire people, often young U.S. citizens, to pick up undocumented migrants near the border and take them to cities such as Tucson or Phoenix. The recruiters tell them not to stop for police but to drive aggressively and recklessly if the police are behind them, officials say.

The Sierra Vista Police Department responded to 19 vehicle pursuits in the city in 2020, and 38 in 2022, McCaa says. Officials often refer to the vehicles suspected of human smuggling as load cars.

“These load car drivers, who are often teenagers and young adults, are encouraged to drive recklessly through our town to discourage pursuits,” McCaa said. “This has created extremely dangerous situations.”

One incident involved a load car driver speeding through an elementary school zone and crashing into a bicyclist, he said.

The police department also has seen an increase in felony cases from 343 in 2020 to 588 in 2022, he said.

“This increase does not stem from violent crimes some might fear plague communities near the border,” he said. “It’s largely because of these load cars. These incidents tie up a significant amount of not only our police department’s time, with our limited manpower, but all law enforcement agencies that are in our region.”

Nicholls agreed that migrants coming through the communities are not causing violent crimes, but rather that a lack of resources to help them get to where they need to go is the problem.

On four occasions, Pima County nearly averted what would have been the release of dozens of people onto the streets in Tucson, Deputy County Administrator Garcia says.

“It is the massive and unrelenting flow and volume of asylum seekers that is the most taxing and that is the biggest challenge for us, for city and county staff, for humanitarian staff and volunteers,” Garcia said. “It is unrelenting and exhausting. Only comprehensive immigration reform is going to fix that.”

New social media campaign from Tucson Border Patrol uses personal stories to deter teens from getting involved in human smuggling.